Do you consider quotations good or bad? As a reader, do you think quotations enhance what you are reading . . . or do they detract from the text?

My personal opinion is that the educated use of quotations enriches writing. (Sloppy quotation is another matter.) Positive contributions made by quotes would include:

They can offer “authoritative” support of a point being made by the writer.

Quotations can offer a refreshing change of pace in a lengthy work.

The selection of the individuals quoted gives me insight into the mind of the current writer.

A well-chosen epigraph piques my curiosity about the chapter which follows.

And, frankly, I simply enjoy a brilliant turn of phrase or a timeless but fresh insight.

I’m not alone in appreciating quotations. It’s no accident The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations is in its seventh edition. Why Do We Quote? describes it this way:

The demand for ODQ remains substantial. It has also spawned numerous sister dictionaries, many themselves appearing in several editions. We have The Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations,… of Literary Quotations,… of Political Quotations,… of Biographical Quotations,… of Medical Quotations,… of American Legal Quotations,…. of Scientific Quotations.… of Phrase, Saying, and Quotation,… of Thematic Quotations,… of Quotations by Subject,… of Modern Quotation,… of Twentieth-Century Quotations, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Quotation. A Little Oxford Dictionary of Quotations has gone through successive editions. There have also been several editions of The Oxford Dictionary of English Proverbs, the first in 1936. There is an avid market, it seems, for quotation collections.

The number of quotation collections is staggering. Read on, and I’ll provide links to some of the compilations available for free download, thanks to public domain laws.

The sheer weight of these books reveals their popularity. And quotations collections are marketable today. In “How Inspirational Quotes became a Whole Social Media Industry,” the author cites a Canadian whose “interest in motivational quotes has proven lucrative, and while he still has a day job in the wireless technology industry, he says that he’s recently been taking home two to three times his regular income from advertising on his website.”

And it all began when, “One day when he was a teenager, he was browsing in a book shop and came across a small book of famous quotations. Something about these pithy sayings appealed to him, and he started to compile his own collection of quotes that particularly resonated.”

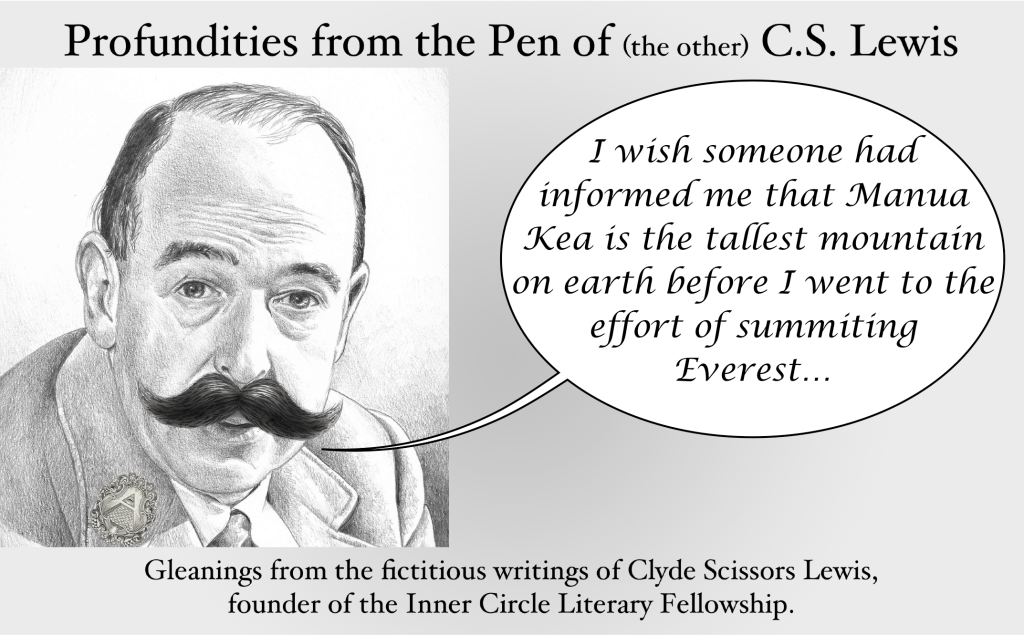

Before the birth of the internet, I invested in several quotation collections—a not uncommon purchase for pastors. I confess to still referring on occasion to The Quotable Lewis to suggest new themes to explore here at Mere Inkling.

C.S. Lewis and Quotations

A beloved lecturer, C.S. Lewis recognized the value of worthy quotation. While few of us have his “eidetic memory,” we can certainly follow his example in using apt quotations to illustrate our points.

Lewis even regarded quotation collections highly enough to compile one. In 1946, he published George MacDonald: An Anthology. It was a tribute to the writings of his “mentor,” who appears in his fictional masterpiece about heaven and hell, The Great Divorce. The anthology remains in print. However, Canadian readers of Mere Inkling can benefit from it falling into public domain status in their Commonwealth. Canadians will find it available for download at this site.

While every reader is capable of enjoying the 365 selections in the volume, Lewis did have a specific intent in the passages he chose.

This collection, as I have said, was designed not to revive MacDonald’s literary reputation but to spread his religious teaching. Hence most of my extracts are taken from the three volumes of Unspoken Sermons. My own debt to this book is almost as great as one man can owe to another: and nearly all serious inquirers to whom I have introduced it acknowledge that it has given them great help—sometimes indispensable help towards the very acceptance of the Christian faith.

Scores of Free Quotation Collections Available to All

Internet Archive has an enormous (free) lending library of books featuring collections of quotations. Many can be “checked out” for temporary use. Other older books are available for download.

Project Gutenberg offers a smaller number, but includes titles they have edited themselves by gleaning pithy phrases from books in their public domain library. Many* of these free (public domain) compilations are linked below.

The massive selection of quotation collections (I quit counting as I approached 100) is daunting. Among those not available for download (which are still accessible for reading) you will note ever more esoteric subject matter. As a whole, we find a small number are collected from prolific individuals, such as Shakespeare, Mark Twain, or John F. Kennedy. Many are generalist, featuring “popular” quotations on a wide range of subjects. Others are thematic, focusing on subjects such as friendship, humor, women, sports, country music, dog [or cat] lovers, climbers, business, motor racing, the military, lawyers, saints, atheists, rock ‘n’ roll, or any of fourscore more themes. Some featuring national or cultural quotations, for example French, Jewish, Scottish, German, etc. And, for those up to the challenge, you can even read Wit and Wisdom of the American Presidents: A Book of Quotations.

🚧 Feel Free to Ignore Everything Below 🚧

Only the smallest attempt has been made here to sort the free volumes. You will find a few general headings below, and a multitude of similarly titled books. One wonders how many of the quotations cited in the larger volumes are common to all of them. Perhaps as you glance through this list, you will see a title or two you might appreciate perusing.

General Quotation Collections

The Oxford Dictionary Of Quotations

(Second Edition: 1953)

The Book of Familiar Quotations

Unnamed Compiler (London: 1860)

Familiar Quotations

John Bartlett (Boston: 1876)

Dictionary of Contemporary⁑ Quotations (English)

Helena Swan (London and New York: 1904)

What Great Men have Said about Great Men: a Dictionary of Quotations

William Wale (London: 1902)

A Cyclopaedia of Sacred Poetical Quotations

H.G. Adams (London: 1854)

The International Encyclopedia of Prose and Poetical Quotations from the Literature of the World

William Shepard Walsh (Philadelphia: 1908)

The Book of Familiar Quotations; being a Collection of Popular Extracts and Aphorisms from the Works of the Best Authors

Unnamed Compiler (London: 1866)

The Book of Familiar Quotations; being a Collection of Popular Extracts and Aphorisms from the Works of the Best Authors

L.C. Gent (London: 1866)

Dictionary of Quotations (English)

Philip Hugh Dalbiac (Long & New York: 1908)

A Dictionary Of Quotations

Everyman’s Library (London: 1868)

Forty Thousand Quotations: Prose and Poetical

by Charles Noel Douglas (New York: 1904)

Three Thousand Selected Quotations From Brilliant Writers

Josiah H. Gilbert (Hartford, Connecticut: 1905)

Stokes’ Encyclopedia of Familiar Quotations: Containing Five Thousand Selections from Six Hundred Authors

Elford Eveleigh Treffry (New York: 1906)

Historical Lights: a Volume of Six Thousand Quotations from Standard Histories and Biographies

Charles Eugene Little (London & New York: 1886)

Great Truths by Great Authors: A Dictionary of Aids to Reflection, Quotations of Maxims, Metaphors, Counsels, Cautions, Aphorisms, Proverbs, &c., &c. from Writers of All Ages and Both Hemispheres

William M. White (Philadelphia: 1856)

Truths Illustrated by Great Authors: A Dictionary of Nearly Four Thousand Aids to Reflection, Quotations of Maxims, Metaphors, Counsels, Cautions, Aphorisms, Proverbs, &c., &c.

William M. White (Philadelphia: 1868)

Handy Dictionary of Prose Quotations

George Whitefield Powers (New York: 1901)

Letters, Sentences and Maxims

Philip Dormer Stanhope Chesterfield (London & New York: 1888)

Poetical Quotations from Chaucer to Tennyson: With Copious Indexes

Samuel Austin Allibone (Philadelphia: 1875)

Prose Quotations from Socrates to Macaulay

Samuel Austin Allibone (Philadelphia: 1880)

Cassell’s Book Of Quotations, Proverbs and Household Words

William Gurney Benham (London & New York, 1907)

Putnam’s Complete Book of Quotations, Proverbs and Household Words

William Gurney Benham (New York, 1926)

Benham’s Book Of Quotations

William Gurney Benham (London: 1949)

Hoyt’s New Cyclopedia Of Practical Quotations

by Kate Louise Roberts (New York: 1927)

Classic Quotations: A Thought-Book of the Wise Spirits of All Ages and all Countries, Fit for All Men and All Hours

James Elmes (New York: 1863)

A Dictionary of Quotations from the English Poets

Henry George Bohn (London: 1902)

A Complete Dictionary Of Poetical Quotations

Sarah Josepha Hale (Philadelphia: 1855)

The Handbook of Quotations: Gleanings from the English and American Fields of Poetic Literature

Edith B. Ordway (New York: 1913)

Carleton’s Hand-Book of Popular Quotations

G.W. Carleton (New York: 1877)

Many Thoughts of Many Minds

George W. Carleton (New York: 1882)

Many Thoughts Of Many Minds

Henry Southgate (London: 1930)

A Manual of Quotations (forming a new and considerably enlarged edition of MacDonnel’s Dictionary of Quotations)

E.H. Michelsen (London: 1856)

A Dictionary of Quotations from Various Authors in Ancient and Modern Languages

Hugh Moore (London: 1831)

Dictionary Of Quotations: from Ancient and Modern, English and Foreign Sources

James Wood (London: 1893)

A Dictionary of Quotations in Prose: from American and Foreign Authors

Anna L. Ward (New York: 1889)

Webster’s Dictionary Of Quotations: A Book of Ready Reference

(London: undated)

Collections of Individual Authors

Quotations from Browning

Ruth White Lawton (Springfield, Massachusetts: 1903)

The Wesley Yearbook: or, Practical Quotations from the Rev. John Wesley

Mary Yandell Kelly (Nashville: 1899)

Quotes and Images From The Works of Mark Twain

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2002)

Widger’s Quotations from the Project Gutenberg Editions of Paine’s Writings on Mark Twain

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2003)

Quotes and Images From The Diary of Samuel Pepys

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From Memoirs of Louis XIV

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From Memoirs of Louis XV and XVI

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2005)

Quotes and Images from the Memoirs of Jacques Casanova de Seingalt

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From Motley’s History of the Netherlands

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images from the Writings of Abraham

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From The Tales and Novels of Jean de La Fontaine

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From The Works of George Meredith

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From Memoirs of Cardinal De Retz

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2005)

Quotes and Images From Memoirs of Count Grammont by Count Anthony Hamilton

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2005)

Widger’s Quotations from the Project Gutenberg Editions of the Works of Montaigne

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2003)

Widger’s Quotations from Project Gutenberg Edition of Memoirs of Napoleon

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2003)

Quotes and Images From the Works of John Galsworthy

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2005)

Quotes and Images From The Confessions of Jean Jacques Rousseau

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

The French Immortals: Quotes and Images

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2009)

Quotes and Images From The Works of Charles Dudley Warner

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From Memoirs of Marie Antoinette

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2005)

Quotes and Images From The Works of Gilbert Parker

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer by Charles James Lever

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From Memoirs of Madame De Montespan

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2005)

Quotes and Images From the Works of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

Quotes and Images From The Works of William Dean Howells

David Widger (Project Gutenberg: 2004)

The Spalding Year-Book: Quotations from the Writings of Bishop [John Lancaster] Spalding for Each Day of the Year

Minnie R. Cowan (Chicago: 1905)

Worldly Wisdom; Being Extracts from the Letters of the Earl of Chesterfield to His Son

William L. Sheppard (New York: 1899)

A Year Book of Quotations: From the Writings of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

with spaces for Autographs and Records (New York: 1896)

The Bernhardt Birthday Book: Being Quotations from the Chief Plays of Madame Sarah Bernhardt’s Repertoire and Other Works

E.M. Evors (London: 1912)

Beauties of Robert Hall

John S. Taylor (New York: 1839)

Shakespeare Gets His Own Section

Everyman’s Dictionary Of Shakespeare Quotations

D.C. Browning (London: 1961)

Shakespearean Quotations

Charles Sheridan Rex (Philadelphia: 1910)

Shakespeare Quotations

Emma Maria Rawlins (New York: 1900)

Quotations from Shakespeare

Edmund Routledge (London: 1867)

A Dictionary of Shakspere Quotations

C.J. Walbran (London: 1849)

The New Shaksperian Dictionary of Quotations

G. Somers Bellamy (London: 1875)

Longer Moral Quotations From Shakespeare

M. Venkatasiah (Mysore/Mysuru, India: 1923)

Dictionary of Shakespearian Quotations: Exhibiting the Most Forceful Passages Illustrative of the Various Passions, Affections and Emotions of the Human Mind

Thomas Dolby (New York: 1880)

Odd, Quaint and Queer Shaksperian Quotations Handsomely and Strikingly Illustrated

Henry McCobb [using pseudonym Shakspere Snug] (New York: 1892)

Thematic Quotation Collections

Quotations from Negro Authors

Katherine D. Tillman (Fort Scott, Kansas: 1921)

Sovereign Woman Versus Mere Man: a Medley of Quotations

Jennie Day Haines (San Francisco: 1905)

About Women: What Men have Said

Rose Porter (New York: 1894)

The Dixie Book of Days

Matthew Page Andrews (London & Philadelphia: 1912)

Living Waters

Alice L. Williams (Boston: 1889)

Green Pastures and Still Waters

Louis Kinney Harlow (Boston: 1887)

Out-of-Doors; Quotations from Nature Lovers

Rosalie Arthur

Ye Gardeyn Boke: a Collection of Quotations Instructive and Sentimental

Jennie Day Haines (San Francisco & New York: 1906)

The Optimist’s Good Morning

Florence Hobart Perin (Boston: 1909)

The Optimist’s Good Night

Florence Hobart Perin (Boston: 1910)

The Book of Love

Jennie Day Haines (Philadelphia: 1911)

Author’s Calendar 1889

Alice Flora McClary Stevens (Boston: 1888)

Proverbs and Quotations for School and Home

John Keitges (Chicago: 1905)

Excellent Quotations for Home and School

Julia B. Hoitt (Boston: 1890)

Borrowings: A Compilation of Helpful Thoughts from Great Authors

Sarah S.B. Yule & Mary S. Keene (San Francisco: 1894)

More Borrowings: the Ladies of First Unitarian Church of Oakland, California

Sarah S.B. Yule & Mary S. Keene (San Francisco: 1891)

Quotations

Norwood Methodist Church (Edmonton, Alberta: 1910).

Goodly Company: a Book of Quotations and Proverbs for Character Development

Jessie E. Logan (Chicago: 1930)

The Atlantic Year Book: Being a Collection of Quotations from the Atlantic Monthly

Teresa J. Fitzpatrick & Elizabeth M. Watts (Boston: 1920)

Here and There: Quaint Quotations, a Book of Wit

H.L. Sidney Lear

Author’s Calendar 1890

Alice Flora McClary Stevens (Boston: 1889)

Catch Words of Cheer

Sara A. Hubbard (Chicago: 1903)

Catch Words of Cheer (new series)

Sara A. Hubbard (Chicago: 1905)

Catch Words of Cheer (third series)

Sara A. Hubbard (Chicago: 1911)

How to Get On, Being, the Book of Good Devices: a Thousand Precepts for Practice

Godfrey Golding (London: 1877)

The Dictionary of Legal Quotations: or, Selected Dicta of English Chancellors and Judges from the Earliest Periods to the Present Time . . . embracing many epigrams and quaint sayings

James William Norton-Kyshe

The Vocabulary of Philosophy, Mental, Moral and Metaphysical: with Quotations and References

William Fleming (Philadelphia: 1860)

Manual of Forensic Quotations

Leon Mead and F. Newell Gilbert (New York: 1903)

Toaster’s Handbook Jokes Stories And Quotations

Peggy Edmund and Harold W. Williams (New York: 1932)

The Banquet Book: A Classified Collection of Quotations Designed for General Reference, and Also an Aid in the Preparation of the Toast List

Cuyler Reynolds (London & New York: 1902)

Like Expressions: a Compilation from Homer to the Present Time

A.B. Black (Chicago: 1900)

Oracles from the Poets: a Fanciful Diversion for the Drawing-Room

Caroline Howard Gilman (London & New York: 1844)

The Sibyl: or, New Oracles from the Poets

Caroline Howard Gilman (New York: 1848)

A Book of Golden Thoughts

Henry Attwell (London & New York: 1888)

A Little Book of Naval Wisdom

Harold Felix Baker Wheeler (London: 1929)

Medical Quotations from English Prose

John Hathaway Lindsey (Boston: 1924)

Psychological Year Book: Quotations Showing the Laws, the Ways, the Means, the Methods for Gaining Lasting Health, Happiness, Peace and Prosperity

Janet Young (San Francisco: 1905)

The Oshawa Book of Favorite Quotations

(Oshawa, Ontario: 1900)

The Pocket Book Of Quotations

Henry Davidoff (New York: 1942)

Quotations for Occasions

Katharine B. Wood (New York: 1896)

Quotations For Special Occasions

Maud Van Buren (New York: 1939)

A Complete Collection of the Quotations and Inscriptions in the Library of Congress

Emily Loiseau Walter

Words and Days: a Table-Book of Prose and Verse

Bowyer Nichols (London: 1895)

The Book of Good Cheer: “A Little Bundle of Cheery Thoughts”

Edwin Osgood Grover (New York: 1916)

The Good Cheer Book

Blanche E. Herbert (Boston: 1919)

Just Being Happy: a Little Book of Happy Thoughts

Edwin Osgood Grover (New York: 1916)

Pastor’s Ideal Funeral Book: Scripture Selections, Topics, Texts and Outlines, Suggestive Themes and Prayers, Quotations and Illustrations

Arthur H. DeLong (New York: 1910)

Quips and Quiddities: a Quintessence of Quirks, Quaint, Quizzical, and Quotable

William Davenport Adams (London: 1881)

The Book of Ready-Made Speeches: with Appropriate Quotations, Toasts, and Sentiments

Charles Hindley (London: 1893)

Suggestive Thoughts on Religious Subjects

Henry Southgate (London: 1881)

Two Thousand Gospel Quotations from the Bible, Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price

Henry H. Rolapp (Salt Lake City, Utah: 1918)

Selected Quotations on Peace and War: with Especial Reference to a Course of Lessons on International Peace, a Study in Christian Fraternity

Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America (New York: 1915)

Book of Science and Nature Quotations

Isaac Asimov & Jason A. Shulman (New York: 1988)

From an Indian Library Collection (not generally public domain)

Foreign (i.e. non-English) Collections

Dictionary of Quotations (Spanish)

[With English Translations]

Thomas Benfield Harbottle and Martin Hume (New York: 1907)

A Literary Manual of Foreign Quotations Ancient and Modern, with Illustrations from American and English Authors

John Devoe Belton (New York: 1891)

Dictionary of Quotations (Classical)

Thomas Benfield Harbottle (London: 1897)

Dictionary of Latin Quotations, Proverbs, Maxims, and Mottos, Classical and Medieval

Henry Thomas Riley (London: 1866)

Treasury of Latin Gems: a Companion Book and Introduction to the Treasures of Latin Literature

Edwin Newton Brown (Hastings, Nebraska: 1894)

A Dictionary of Oriental Quotations (Arabic and Persian)

Claud Field (London & New York: 1911)

A Little Book of German Wisdom

Claud Field (London: 1912)

Dictionary Of Foreign Phrases And Classical Quotations

Hugh Percy Jones (Edinburgh: 1908)

Dictionary Of Quotations: in Most Frequent Use, Taken Chiefly from the Latin and French, but Comprising Many from the Greek, Spanish and Italian Languages

[Translated into English]

D.E. MacDonnel (London: 1826)

A Dictionary Of English Quotations And Proverbs

With translations into Marathi

C.D. Deshmukh (Poona/Pune, India: 1973)

Classical and Foreign Quotations: a Polyglot Manual of Historical and Literary Sayings, Noted Passages in Poetry and Prose Phrases, Proverbs, and Bons Mots

Wm. Francis Henry King (London: 1904)

* Too many.

⁑ A bit of irony in this title, since it was written over 115 years ago.