Barbers, and hairdressers, play a unique role in society. Let’s consider now two barbers whose interactions with great Christians contributed to our understanding of prayer.

Before we do, however, I wish to share another aspect of C.S. Lewis’ life which parallels many of our own. The great professor and author was exceptional for his knowledge, but in most other ways was just like us.

One example of Lewis’ normalness, is seen in his interactions with barbers. Due to the survival of much of his correspondence, we can witness a perennial tension—the desire of fathers that their sons cut their hair.

As a veteran whose adult son had a ponytail for several years, I understand the frustration of Lewis’ father, the Irish solicitor, when his son Jack lacked diligence in maintaining a neat appearance. In my own case, the die had been cast from my youth. Growing up in the late sixties, I did manage to sport a thick contemporary mane which chafed my own father, but too much of my youth was spent with a crewcut, the haircut-of-choice for my dad, the Marine Corps sergeant.

Presumably, while young Jack was still at home, his parents saw to it his hair was attended to. After his mother Florence’s death, and his move to boarding school, haircuts were a curious recurring theme in Lewis’ correspondence with his “Papy.” Below are a few of young Jack’s passing remarks on the subject.

Today I did a thing that would have gladdened your heart: walked to Leatherhead (for Bookham does not boast a barber) to get my hair cut. And am now looking like a convict (1914).

My dear Papy, Thanks very much for the photographs, which I have duly received and studied. They are artistically got up and touched in: in fact everything that could be desired–only, do I really tie my tie like that? Do I really brush my hair like that? Am I really as fat as that? Do I really look so sleepy? However, I suppose that thing in the photo is the one thing I am saddled with for ever and ever, so I had better learn to like it. Isn’t it curious that we know any one else better than we do ourselves? Possibly a merciful delusion (1914).

I am very sorry to hear that you were laid up so long, and hope that you now have quite shaken it off. I have had a bit of a cold, but it is now gone, and beyond the perennial need of having my hair cut, I think you would pass me as ‘all present and correct’ (1921).

I am afraid this has been an egotistical letter. But it is dull work asking questions which you can’t (at any rate for the moment) give a reply to. You do not need to be told that I hope you are keeping fairly well and that I shall be glad to hear if this is the case. For myself—if you came into the room now you would certainly say that I had a cold and that my hair needed cutting: what is more remarkable: you would (this time) be right in both judgements. Your loving son, Jack (1928)

Lewis’ High Street Barber

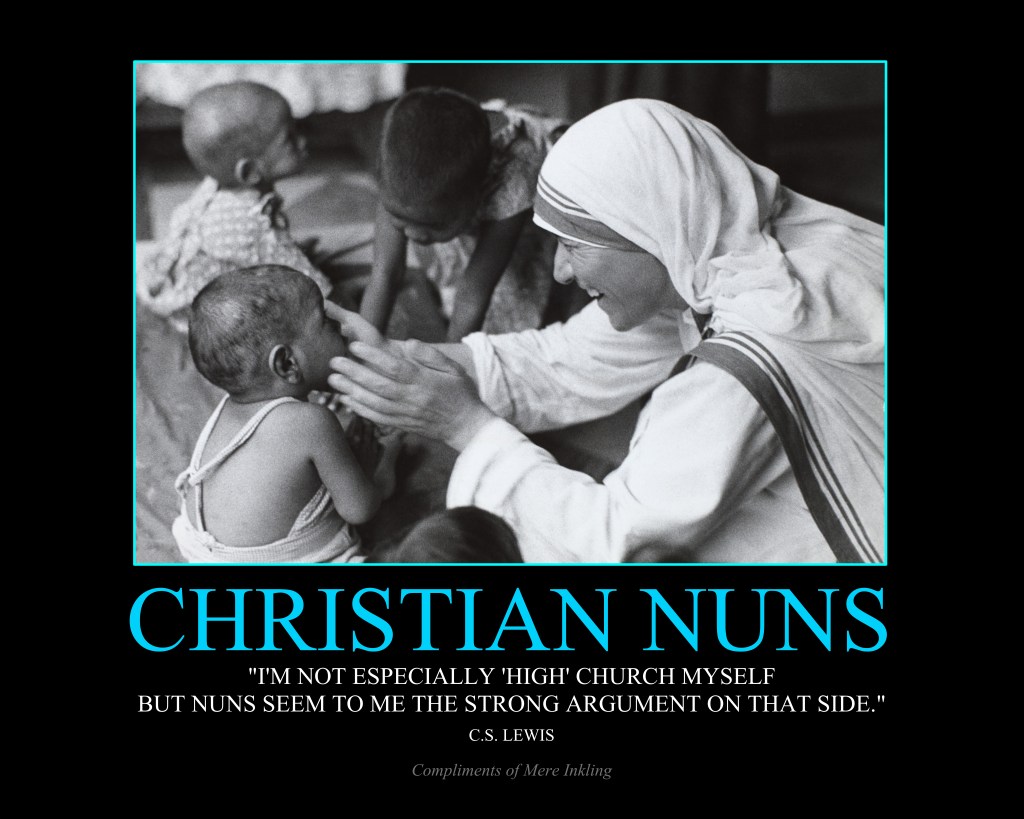

In the early 1950s, C.S. Lewis developed a meaningful relationship with his barber, based on their shared faith. Before we consider an essay inspired, in part, by this friendship, this 1951 letter reveals the affection Lewis held for the man.

My brother joins me in great thanks for all your kindnesses, and especially on behalf of dear little comical Victor Drewe—our barber, as you know.

When he cut my hair last week he spoke in the most charming way of his wife who has just been ill and (he said) ‘She looks so pretty, Sir, so pretty, but terribly frail.’ It made one want to laugh & cry at the same time—the lover’s speech, and the queer little pot-bellied, grey-headed, unfathomably respectable figure.

You don’t misunderstand my wanting to laugh, do you? We shall, I hope, all enjoy one another’s funniness openly in a better world.

Years later, C.S. Lewis would write a profound essay on “The Efficacy of Prayer.”

Some years ago I got up one morning intending to have my hair cut in preparation for a visit to London, and the first letter I opened made it clear I need not go to London. So I decided to put the haircut off too.

But then there began the most unaccountable little nagging in my mind, almost like a voice saying, “Get it cut all the same. Go and get it cut.” In the end I could stand it no longer. I went.

Now my barber at that time was a fellow Christian and a man of many troubles whom my brother and I had sometimes been able to help. The moment I opened his shop door he said, “Oh, I was praying you might come today.” And in fact if I had come a day or so later I should have been of no use to him.

It awed me; it awes me still. But of course one cannot rigorously prove a causal connection between the barber’s prayers and my visit. It might be telepathy. It might be accident. . . .

Our assurance—if we reach an assurance—that God always hears and sometimes grants our prayers, and that apparent grantings are not merely fortuitous, can only come [through a relationship which knows the promiser’s trustworthiness].

There can be no question of tabulating successes and failures and trying to decide whether the successes are too numerous to be accounted for by chance. Those who best know a man best know whether, when he did what they asked, he did it because they asked.

I think those who best know God will best know whether He sent me to the barber’s shop because the barber prayed.

You can read “The Efficacy of Prayer” in its entirety here. Or, should you prefer, you can hear it expertly read here.

The Story of Another Godly Barber

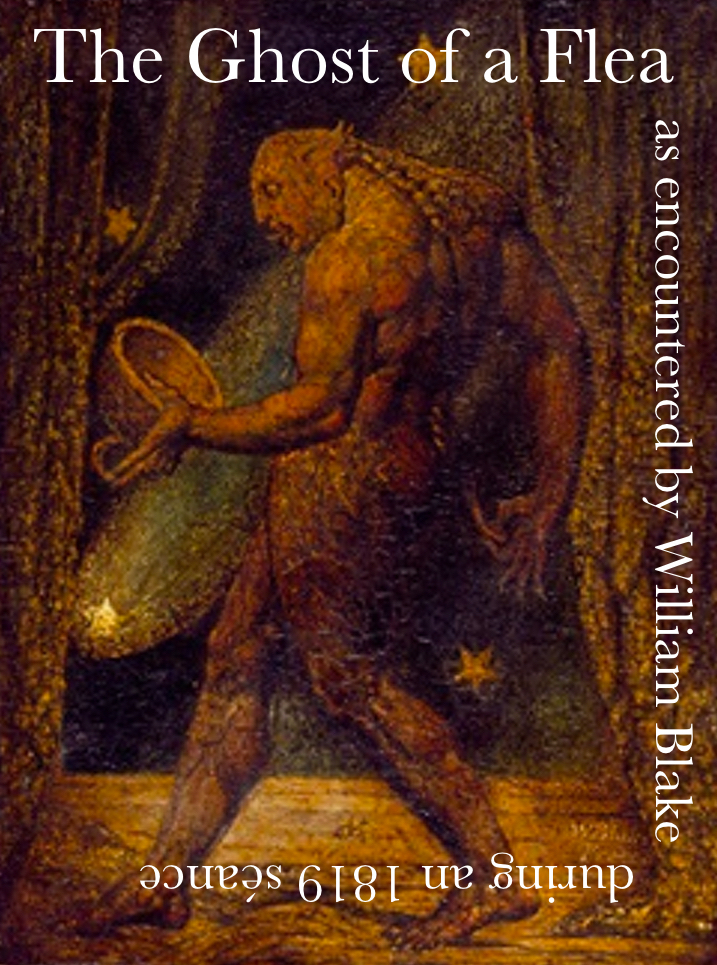

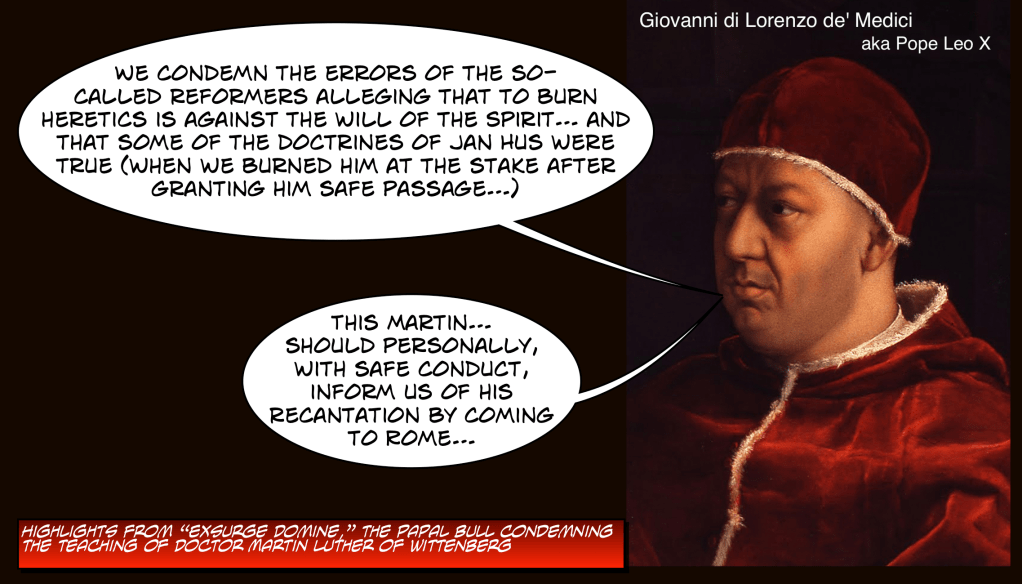

Four centuries before C.S. Lewis honored his barber by forever associating his name with the subject of prayer, the church reformer Martin Luther did the same. Luther’s friend was named Peter, and he lived during an age when skilled barbers also served as surgeons. According to the Barber Surgeons Guild,

The early versions of the Hippocratic Oath cautioned physicians from practicing surgery due to their limited knowledge on its invasive nature. During the Renaissance, Universities did not provide education on surgery, which was deemed as a low trade of manual nature.

Barber surgeons who were expertly trained in handling sharp instruments for invasive procedures quickly filled this role in society. Barber surgeons were soon welcomed by the nobility and given residence in the castles of Europe where they continued their practice for the wealthy. These noble tradesmen, armed with the sharpest of blades, performed haircuts, surgeries and even amputations.

One church historian describes the Reformation context in an article entitled “Praying with Peter the Barber.”

Early in the year 1535, Peter Beskendorf became the most famous hairdresser of the reformation. He was Martin Luther’s barber and wrote to the great reformer asking for advice on how to pray.

Peter not only had a reputation as the master barber of Wittenberg, but he had a reputation for godliness and sincerity in his love for the Word of God. He was one of Luther’s oldest and best friends, so his request is not all that surprising.

What is surprising, however, is that Luther took the time out of his immensely busy reformation schedule to write him a thirty-four-page reply with theological reflections and practical suggestions about how he ought to approach prayer to the Almighty God.

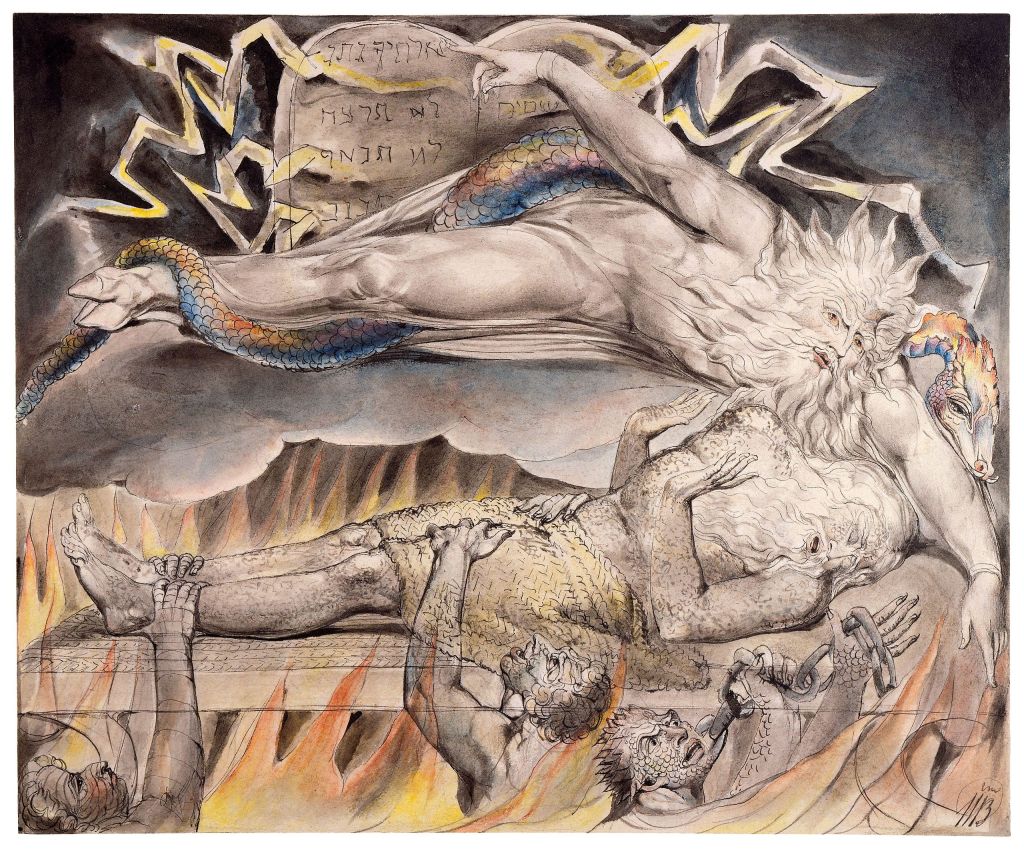

In “Cutting Hair and Saying Prayers,” a lay theologian describes the focus of Martin Luther’s counsel.

When Luther’s barber, Peter Beskendorf, asked him how to pray, Luther wrote him an open letter that has become a classic expression of the “when, how, and what” of prayer. It is as instructive today as when it was first penned in 1535. . . .

Luther spends the bulk of his letter discussing what to pray. Implicitly in his letter, Luther teaches that God’s word is the content of our prayers.

Luther graces the beginning of the book with a sincere prayer of blessing. “Dear Master Peter: I will tell you as best I can what I do personally when I pray. May our dear Lord grant to you and to everybody to do it better than I! Amen.”

In a very interesting essay entitled “Warrior Saints,” a Marquette professor commends the “sweet and practical booklet,” writing that “today this work is justly celebrated as a minor classic that both epitomizes Luther’s spirituality and powerfully suggests what a deep and lasting impact he would make on the lives of his many followers.”

Volume 43 of Luther’s Works includes the treatise. In the collection’s introduction to the document, it includes a heartbreaking event that followed its publication.

Luther wrote the book early in 1535 and it was so popular that four editions were printed that year.

At Easter a tragedy befell Peter. He was invited to the home of his son-in-law, Dietrich, for a convivial meal the Saturday before Easter, March 27, 1535. Dietrich, an army veteran, boasted that he had survived battle because he possessed the art of making himself invulnerable to any wound. Thereupon the old barber, doubtlessly intoxicated, plunged a knife into the soldier’s body to test his boast. The stab was fatal.

Master Peter’s friends, including Luther, intervened for him, and the court finally sent him into exile. . . . He lost all his property and, ruined and impoverished, spent the rest of his life in Dessau.

Such was the sad course of Beskendorf’s life. One can only hope that, as his life itself had been spared, Peter experienced some sort of healing and peace. Such blessings, after all, are often the fruit of prayer.

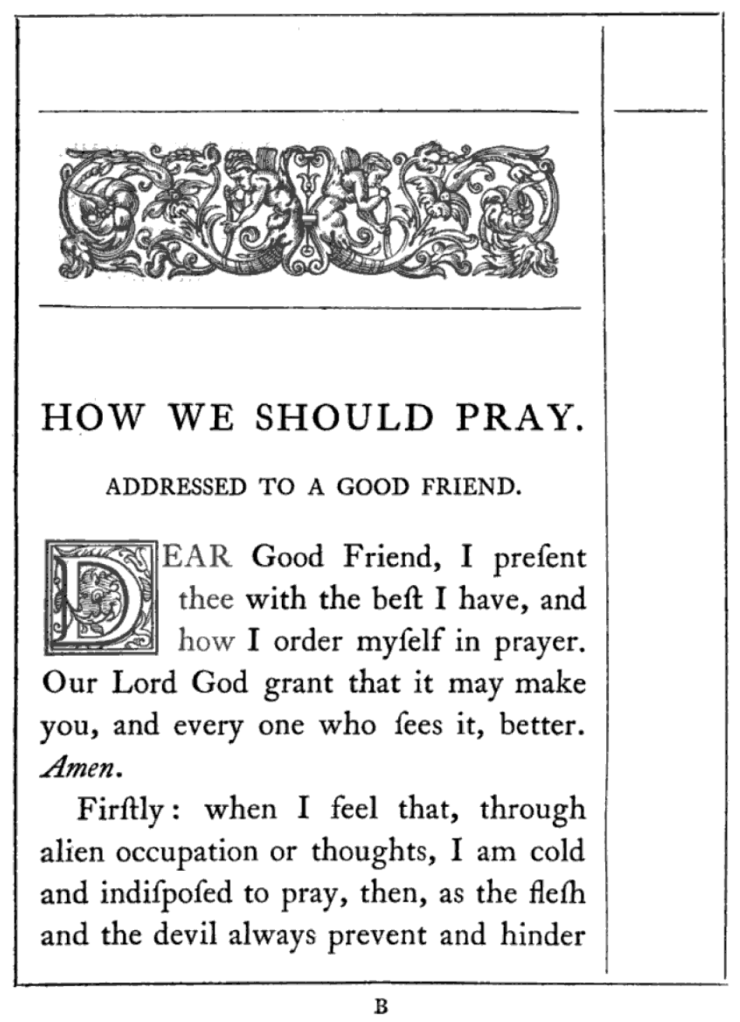

Luther’s humble essay on prayer remains in print today. If you would like to read or own it for free, I have found a London edition entitled The Way to Prayer.

One caveat, which might trouble some readers: since the translation was published in 1846, it employs the “medial S,” the one that looks more like a lower case “F.”* Whichever edition you choose to read, you will not be disappointed.

* The medial S is sometime referred to as the long S. You can read about its history in this interesting article.

The history of S is a twisting, turning path. Until around the 1100s or so, the medial S was the lowercase form of the letter, while the curvy line we use today was the uppercase form. But over time, the regular S, technically known as the “round S” or “short S,” started being used as a lowercase letter, too.

By the 1400s, a new set of S usage rules was established: The medial S would be used at the beginning of a lowercase word or in the middle of a word, while the round S would appear either at the end of a word or after a medial S within a word, as in “Congreſs” (which appears in the first line of Article I of the Constitution).