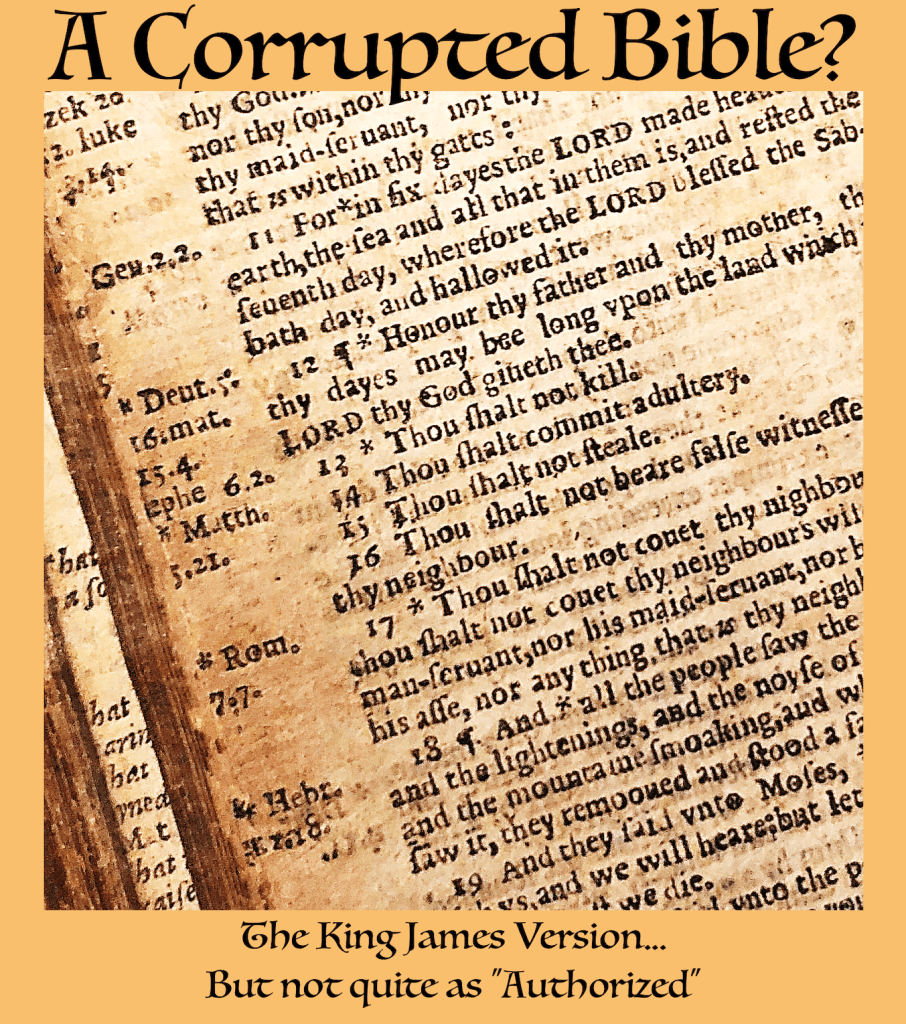

While the title of this post will be shocking to some, it’s far less scandalous than the typographical error discussed below. Due to two misprints appearing in a 1641 edition of the King James Bible (KJV), the publication has been labeled the “Wicked Bible.”

Translating the Scriptures is a necessary, and demanding, task. The early editions of the KJV (which was preceded by the Wycliffe Bible) reveal how vulnerable the words themselves were to being altered during the typesetting process.

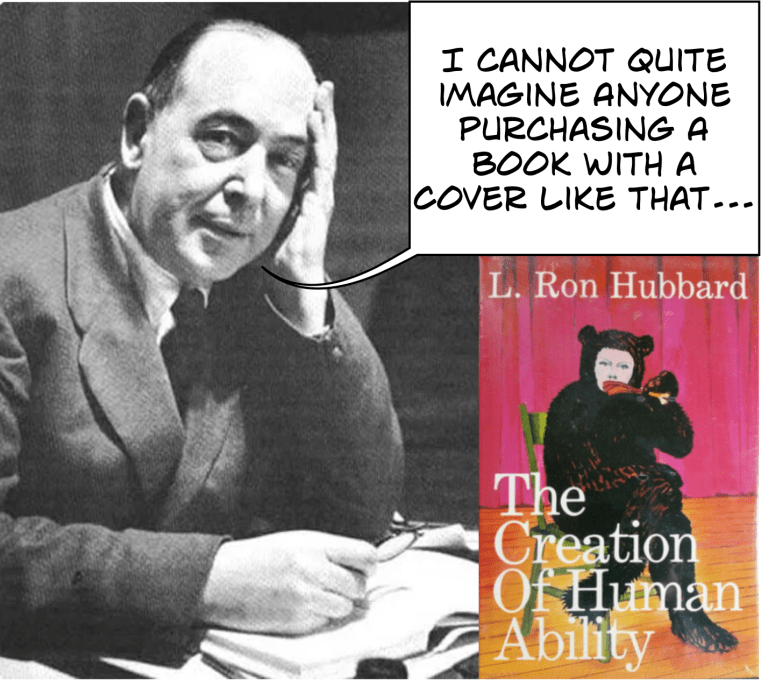

I’ve written about this subject a number of times during the past decade, and even devoted a column to “C.S. Lewis’ School of Translation,” which is about something even more important than merely translating words. There I quote one of the great author’s deepest hopes.

What I want is to be the founder of a school of ‘translation . . .’ Where are my successors? (correspondence, 7 October 1945).

Returning to the seventeenth century book with its unfortunate errors, we witness an example of how even a solid translation can be derailed by careless (or malevolent) typesetters.

The magnitude of the mistake discovered in this particular edition caused its suppression, and most copies were destroyed. While some still exist in private hands, only fifteen remain in public collections. One of these made its way to New Zealand before being identified in 2018.

A Truly Scandalous Misprint

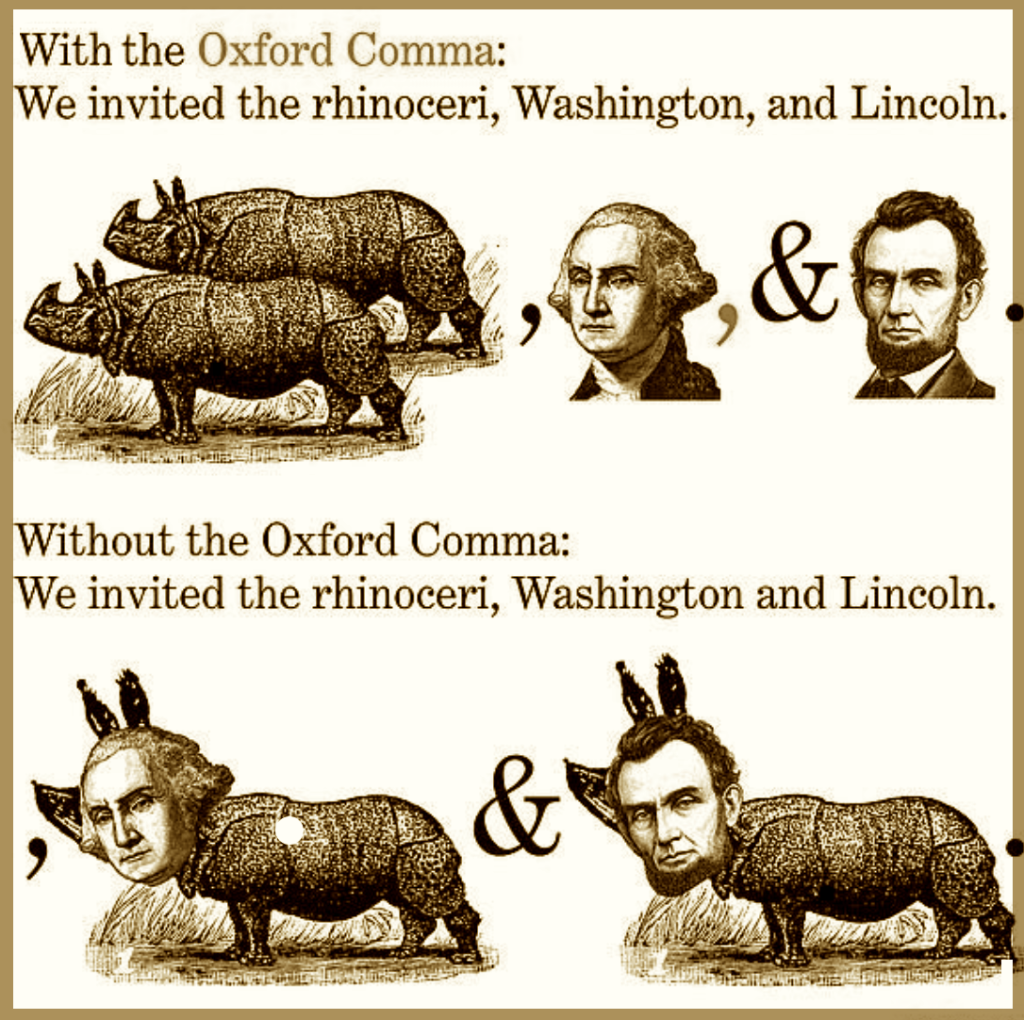

It would be one thing if a printer accidently dropped the final “e” from “breathe,” leaving the word “breath.” Even substituting an errant “w” for the “b,” would create an alternate word that would greatly muddle a passage . . . but still not appear remotely “wicked.”

However, a 1631 mistake in an English Bible literally turned a passage – one of the Ten Commandments, no less – on its head. Rather than reading “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” this edition declares, “Thou shalt commit adultery” (Exodus 20:14).

The consequences of this disaster were significant, particularly for His Majesty’s official printers. In Cyprianus Anglicanus by royalist priest Peter Heylyn (1599-1662), we learn the details. (You can download a free facsimile of the volume which includes many other fascinating facts.) The passage related to the misbegotten tome reads as follows:

His Majesties Printers, at or about this time [1632], had committed a scandalous mistake in our English Bibles, by leaving out the word Not in the Seventh Commandment.

His Majesty being made acquainted with it by the Bishop of London, Order was given for calling the Printers into the High-Commission where upon the Evidence of the Fact, the whole Impression was called in, and the Printers deeply fined, as they justly merited.

Reports of Cases in the Courts of Star Chamber and High Commission, penned by Samuel Rawson Gardiner in 1886, includes a detailed account of the court’s findings. (Due to their uniqueness, I have transposed the full account, as found in two sections, as a footnote below.) One passage describes a second “gross error.”

. . . showed the two grossest errors, vizt. “Shalt commit adultery” and “great asse:” for “shalt not commit adultery” and “greatnesse…”

The second of these blunders occurs in Deuteronomy 5:24, which properly reads “Behold, the Lord our God hath shewed us his glory and his greatness.” (It should be noted that the word asse would most commonly be associated with donkeys.)

The magnitude of these mistakes can only be understood when one recognizes how reverentially the Scriptures were regarded at this time. C.S. Lewis would suggest that during an age when the Bible has been relegated to historic literature, it is difficult for us to comprehend the seriousness of this matter.

It is very generally implied that those who have rejected its theological pretensions nevertheless continue to enjoy it as a treasure house of English prose. It may be so. There may be people who, not having been forced upon familiarity with it by believing parents, have yet been drawn to it by its literary charms and remained as constant readers.

But I never happen to meet them. Perhaps it is because I live in the provinces. But I cannot help suspecting, if I may make an Irish bull, that those who read the Bible as literature do not read the Bible. (“The Literary Impact of the Authorised Version”).

In “Challenges in Printing Early English Bibles,” you can read about other Bibles featuring noteworthy mistakes. In two, “peacemakers” become “placemakers,” and “murmurers” are transformed into “murderers.” Another example, in the very first edition of the KJV, finds Jesus’ ancestor Ruth referred to by the male pronoun, due to the accidental dropping of an “s.”

More troubling is another early KJV Bible where “the text of Psalm 14 [reads], “The fool hath said in his heart there is a God,” rather than “The fool hath said in his heart there is no God.”

Worst of all, in terms of blasphemous connotations, would likely be the so-called “Judas Bible.”

In the 1609 Geneva Bible, the typesetters mistakenly replaced Jesus’s name with that of Judas. John 6:67 reads: “From that time many of his disciples went back, and walked no more with him. Then said Judas unto the twelve, Will ye also go away?”

Fortunately, modern editions of the Jewish and Christian Scriptures undergo thorough proofreading, so this sort of error is rare today. Still, typos will persist as long as the remotest possibility of error exists.

Those among us who have sought to have our writing published by traditional publishers may relate to the example with which we end. C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien and even Mark Twain faced challenges working with some of their editors and publishers.

With all of the printing mishaps in the early English Bible, it is only appropriate that one of the editions was called “The Printers Bible.”

This text, published in about 1702, takes its name from a typesetting error found in Psalm 119, which should have read “Princes have persecuted me without a cause” but was mistakenly printed as “Printers have persecuted me.”

Full references from Reports of Cases in the Courts of Star Chamber and High Commission by Samuel Rawson Gardiner (1886).

Mr Barker the printer. There is a cause begunne against him for false printeing of the Bible in divers places of it, in the Edition of 1631, vizt., in the 20 of Exod[us], “Thou shalt committ adultery”; and in the fifte of Deut[eronomy] “The Lord has shewed his glory, and his great asse”; and for divers other faults; and that they had printed it in very bad paper. And the Bishop of London showed that this would undoe the trade, and was a most dishonorable thing; that they of the church of Rome are soe carefull, that not a word or letter is to be found amisse in their Ladie’s Psalter and other superstitious books; and that we should not be soe carefull in printinge the sacred Scriptures; and that they in Holland, at Amsterdam, had gott up an English presse, and had printed the Bible in better paper, and with a better letter, and can undersell us 18d. in a Bible. Mr Barker and his partners endeavored in partt to excuse themselves, and had advocates to speake for them, and were willing to submitt, and promised to amend their faults; but the Court would not remitt their offense, but the cause was ordered to goe on.

The Printers having answered move the Court to passe by their oversight being the fault of the workmen but the King’s Advocate desired they might make their defense legally and the cause to go onto hearing: and that he might have liberty to put in additional articles against them. The Bishop of London would have the Church sett upright in her reputacion, that we are as carefull in printeing the Bible as they are of their Jesus’ psalter : and whereas the Printers say this is stirred up by the malice of one man against them; The Bishop saith he stirred not till the Bible was sould into his house, bought by his footman: and he saith the printinge is soe bbad and the paper too that, if it be not mended shortlie, they wilbe put downe by those of Amsterdam and their trade spoyled, and showed for the two grossest errors, vizt. “Shalt commit adultery” and “great asse:” for “shalt not commit adultery” and “greatnesse…” The Arch Bishop of Canterbury saith, that the Printers that print for his Matie have a very profitable place, and therefore should be more carefull. I knew the tyme when greater care was had about printeing, the Bibles especiallie, good compositors and the best correctors were gotten being grave and learned men, and the paper and letter rare and faire every way of the best; but now the paper is naught, the composers boyes, and the correctors unlearned: There is a farmer and he makes the benefit, and careth for nothing about it. They heretofore spent their whole time in printeing, but these looke to gaine, gaine, gaine, then they are not to be commended: Well, let them looke to it: and let the cause proceed, saith the ArchBishop. London. “There was a great deale of doo between you of this Citty and those of Cambridge heretofore about the priviledge of printeing the Bible and psalms which they of Cambridge claymed; then the Bible was exactlie printed, now you have forced the Cambridg printer to an agreement, now noe bible is right printed.

[It appears this volume itself would have benefited from having more diligent “correctors.” Perhaps most curiously, two spellings of the word printing – “printinge” and “printeing” – appear in this publication.]

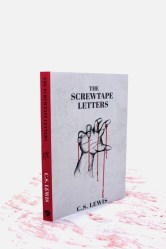

I wanted to convey an accurate image of the book, while also allowing for some ambiguity so the reader could project their own meaning onto the cover. C.S. Lewis books are traditionally marketed toward Christian audiences, and often have light-hearted covers. . . . I wanted the books to appeal to a non-Christian audience, and I wanted the books to have a gritty and more emotional feeling, while also alluding to the extraordinary qualities inside the book.

I wanted to convey an accurate image of the book, while also allowing for some ambiguity so the reader could project their own meaning onto the cover. C.S. Lewis books are traditionally marketed toward Christian audiences, and often have light-hearted covers. . . . I wanted the books to appeal to a non-Christian audience, and I wanted the books to have a gritty and more emotional feeling, while also alluding to the extraordinary qualities inside the book.