Amanda McKittrick Ros (1860-1939) was an Irish poet and novelist beloved by the Oxford Inklings. “Beloved” here is used in the sense of treasured for its distinctiveness, rather than admired for its artistry.

An article about Ros in Smithsonian Magazine is subtitled: “Amanda McKittrick Ros predicted she would achieve lasting fame as a novelist. Unfortunately, she did.”

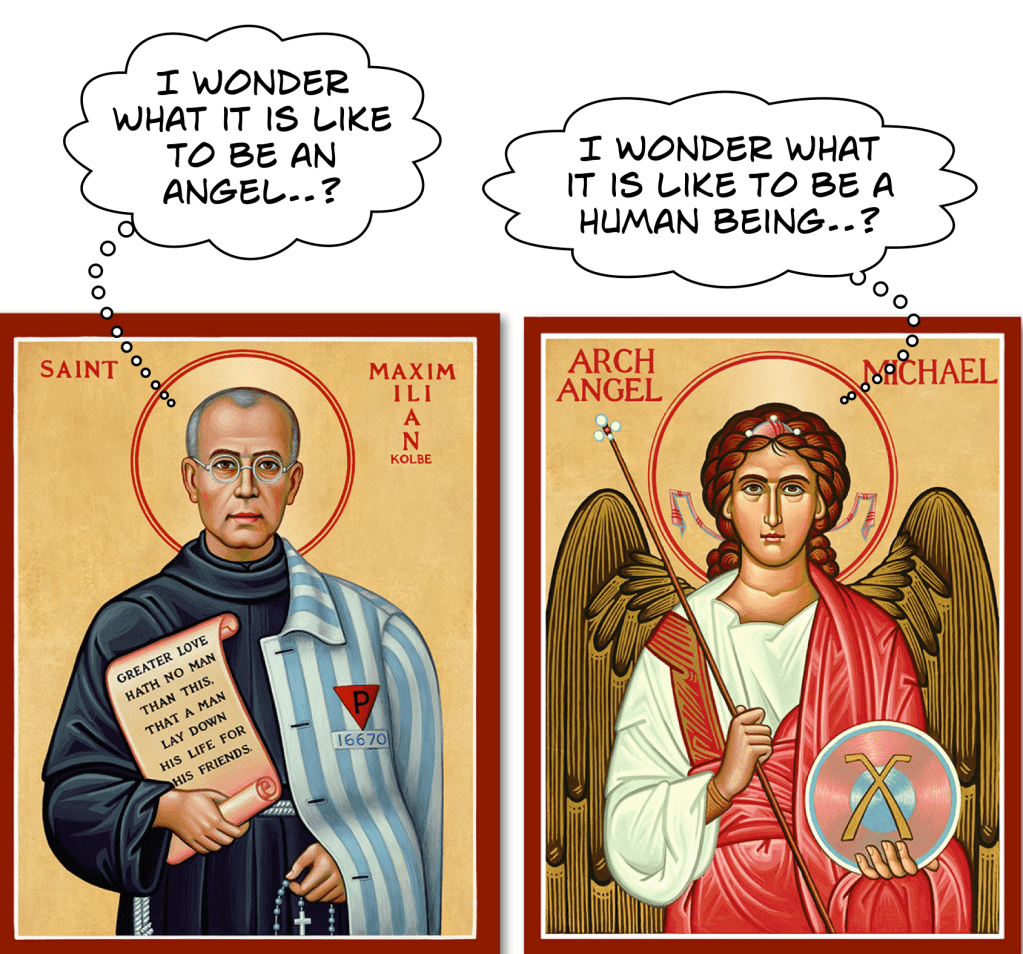

So how is it that a writer described by the Oxford Companion to Irish Literature (OCIL) as authoring “unconscious comedy of a very high order” came to occupy a special place within the company of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and their literary fellows? Why did they begin reading her works as a sort of contest, with the challenge of neither laughing nor smiling as they did so?

It was not because her mother (or she herself) christened her after a character in The Children of the Abbey, published in 1796. (Her initial name was “Anna.”)

No, it was due to an intrinsic element of her frequently alliterative artistry, described by OCIL in the following manner.

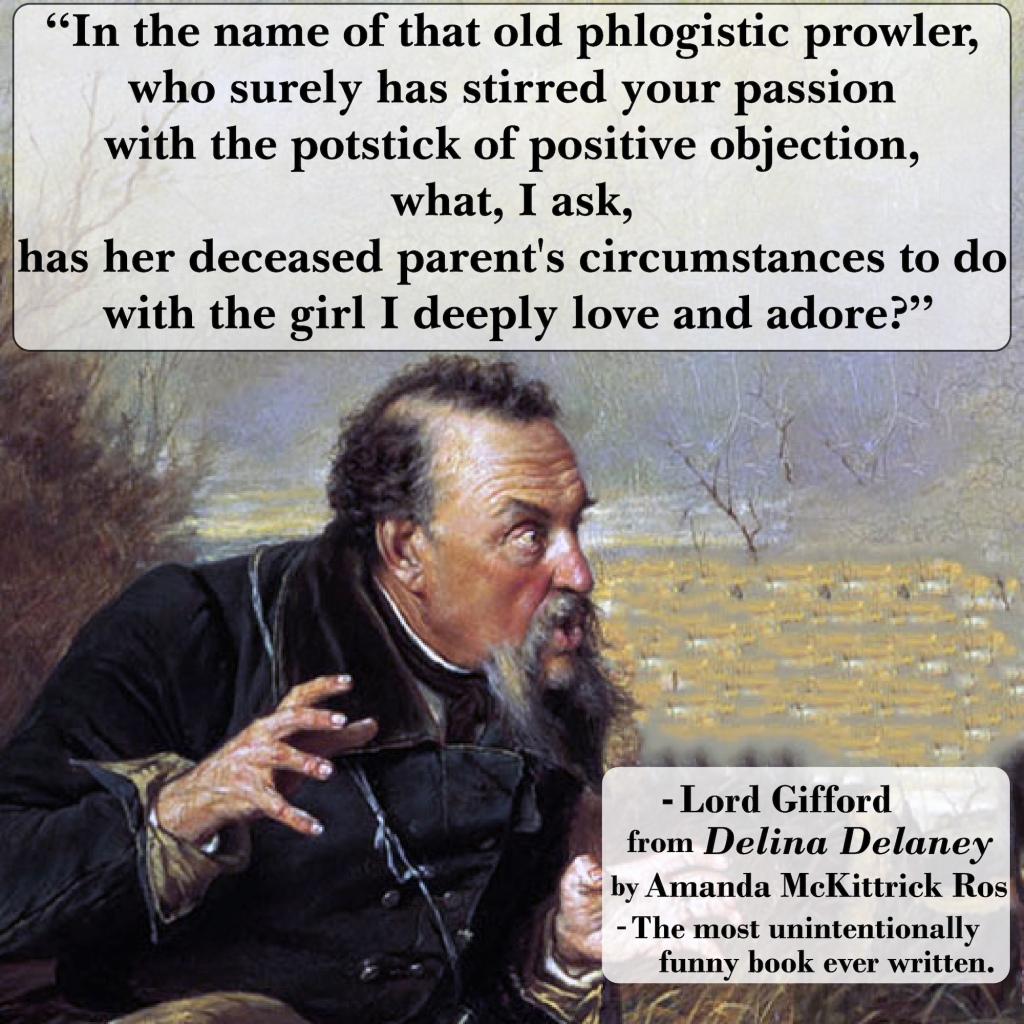

She published two sentimental romances, Irene Iddlesleigh (1897) and Delina Delany (1898), both in an idiosyncratic manner that provides unconscious comedy of a very high order. . . .

Most of her published writings appeared posthumously as a result of literary curiosity.

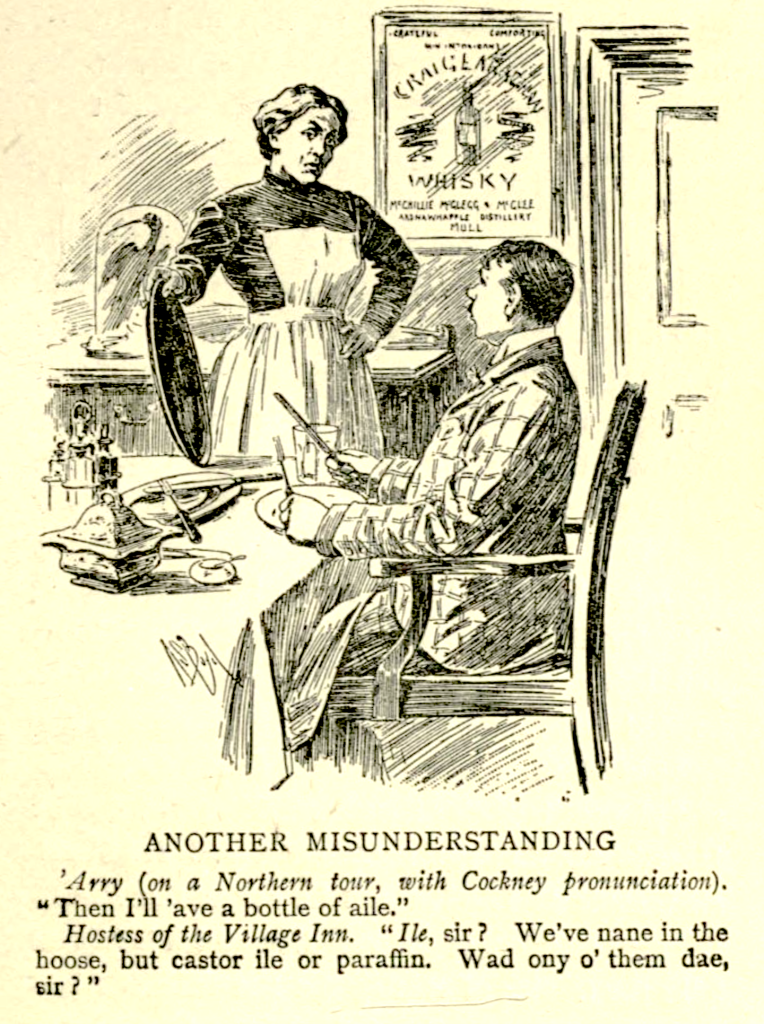

Many writers would agree that writing comedy is quite challenging. Comedy Crowd is devoted to helping writers gain some skill in this arena, and if you take a moment to check out their video about failed puns – after you finish reading this post – you won’t be disappointed.

As one commenter on SleuthSayers puts it, “. . . writing humor isn’t easy. It’s even dangerous: trying to be funny and failing would be almost as bad as being funny when you’re trying to be serious.” Sadly, the worst of these options proved to be the fortune of poor Amanda.

Even her native Northern Ireland Library Authority confesses that her “writing style can only be described as elaborate, melodramatic, using startling descriptions with mixed metaphors and inappropriate alliteration with the result being unintentionally hilarious.”

In her collection “Poems of Puncture,” I came across a piece titled “Reverend Goliath Ginbottle.” Being a reverend myself, I eagerly listened to a LibriVox recording of the poem (which you can download for free from Internet Archive), and I was not disappointed. Her description of this “viper of vanity” and her joy at his ultimate judgment was delightfully colorful. Or, should you prefer to hear a diatribe against a corrupt lawyer, listen to Mickey Monkeyface McBlear, who bore “a mouth like a moneybox.”

TV Tropes has an article about Ros which attributes a dozen tropes to her pen.

In the Style of: Aldous Huxley noted that Ros wrote in the 16th century style of Euphuism. Susan Sontag decades later stated that Euphuism was the progenitor of camp, which would explain why literary greats found her writing so hilarious.

Those curious about euphuism can read John Lyly’s Euphues: the Anatomy of Wit; Euphues and His England which is filled with delights unnumbered. Originally two volumes, the books were published in the sixteenth century.

C.S. Lewis was a serious enough “fan” of Ros’ writings to share his affection for them with Cambridge Classicist Nan Dunbar. C.S. Lewis scholar Joel Heck has written a worthwhile article about the ongoing friendship between the two professors.

For a detailed study of the literary relationship between Amanda McKittrick Ros and the Inklings, I highly recommend the article by Anita Gorman and Leslie R. Mateer which appeared in Mythlore.

As they describe, even before the Inklings added occasional readings of her work to their gatherings, as early as 1907 there was in Oxford a society devoted to weekly readings of her works. The authors pose, and then proceed to answer, the following question.

What . . . impelled C.S. Lewis and his mates to read aloud Ros’s work? Yes, the improbable plots, silly characters, and nonexistent themes may have played a role, but were those enough to captivate the Inklings and to give rise to Delina Delaney dinners and Amanda Ros societies?

After all, many writers have written improbable plots about improbable people, and these writers have enjoyed short-lived reputations, if any reputations at all. Yet Amanda lives on.

For Those with Stout Constitutions

Mere Inkling offers one final look back at the transcendent poetry of Amanda McKittrick Ros. This infamous selection can be found at the aptly named Pity the Readers: Horribly Excellent Writing website.

“Visiting Westminster Abbey”

(from Fumes of Formation)Holy Moses! Have a look!

Flesh decayed in every nook!

Some rare bits of brain lie here,

Mortal loads of beef and beer,Some of whom are turned to dust,

Every one bids lost to lust;

Royal flesh so tinged with ‘blue’

Undergoes the same as you.

These morose words bring to mind another verse, composed in the form of a song by the artists of Monty Python. It appeared on Monty Python’s Contractual Obligation Album as “Decomposing Composers.”

They’re decomposing composers.

There’s nothing much anyone can do.

You can still hear Beethoven,

But Beethoven cannot hear you. . . .Verdi and Wagner delighted the crowds

With their highly original sound.

The pianos they played are still working,

But they’re both six feet underground.They’re decomposing composers.

There’s less of them every year.

You can say what you like to Debussy,

But there’s not much of him left to hear.

Yes, similarly morbid verse, but offered here to provide a sharp contrast between types of humor. Monty Python is the epitome of Camp, which according to Susan Sontag,

sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a “lamp;” not a woman, but a “woman.” To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role. It is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater.

Although Sontag notes “one must distinguish between naïve and deliberate Camp,” she argues the “pure examples of Camp are unintentional.” She considers self-conscious efforts, such as Noel Coward (and presumably Monty Python as well) as “usually less satisfying.”

Another perspective offers a helpful dichotomy to distinguish between “intentionality: whether camp deliberately cultivated (‘high’ camp) is the same to that of the unintentional kind (‘low’ camp).”

Personally, I often enjoy high (nonvulgar) camp humor – witty silliness that scoffs at life’s peculiarities. As for unintentional, “low” camp such as we find in Ros, I typically feel a flash of guilt at hurting (even posthumously) the feelings of a writer. Most of us writers are, after all, a sensitive and vulnerable breed.

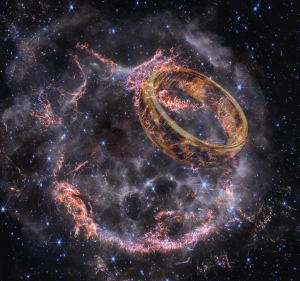

The enlightening illustrations accompanying this article are from Amanda McKittrick Ros Society Promotional Memes, ably captained by Dan Morgan.