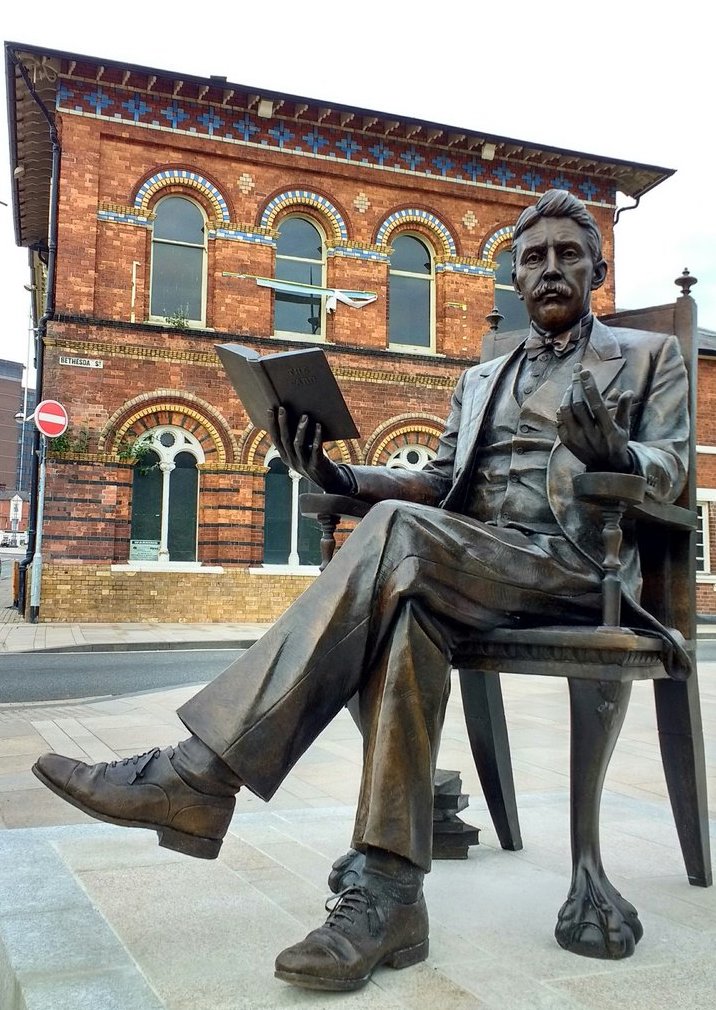

George MacDonald (1824-1905) was a prolific Scot writer. His legacy was amplified due to his influence on G.K. Chesterton and C.S. Lewis. (He was also a friend of Mark Twain.) An essay, originally presented as a speech by G.K. Chesterton, is available online.

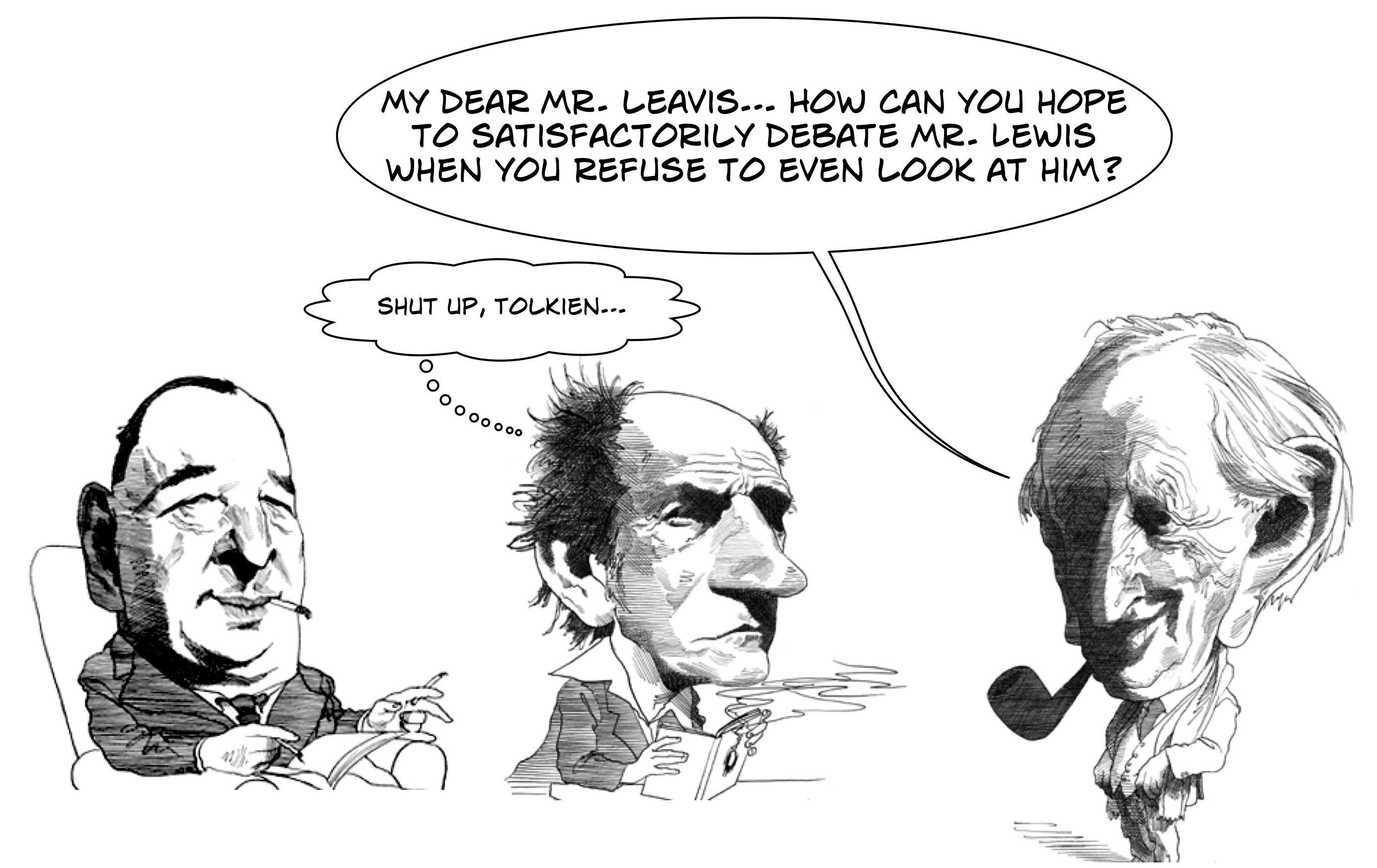

Chesterton goes so far as to say, “if to be a great man is to hold the universe in one’s head or heart, Dr. MacDonald is great. No man has carried about with him so naturally heroic an atmosphere.” Listen to his description of that special type of literature that inspired many Inklings, chiefly C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.

Many religious writers have written allegories and fairy tales, which have gone to creating the universal conviction that there is nothing that shows so little spirituality as an allegory, and nothing that contains so little imagination as a fairy tale. But from all these Dr. MacDonald is separated by an abyss of profound originality of intention.

The difference is that the ordinary moral fairy tale is an allegory of real life. Dr. MacDonald’s tales of real life are allegories, or disguised versions, of his fairy tales.

It is not that he dresses up men and movements as knights and dragons, but that he thinks that knights and dragons, really existing in the eternal world, are dressed up here as men and movements.

C.S. Lewis, for his part, praised MacDonald as instrumental in tilling the soil for his eventual conversion to Christianity. He was on the defensive, since the writers which most inspired him shared a common flaw – they were Christians.

All the books were beginning to turn against me. Indeed, I must have been as blind as a bat not to have seen, long before, the ludicrous contradiction between my theory of life and my actual experiences as a reader.

George MacDonald had done more to me than any other writer; of course it was a pity he had that bee in his bonnet about Christianity. He was good in spite of it.

Chesterton had more sense than all the other moderns put together; bating, of course, his Christianity. Johnson was one of the few authors whom I felt I could trust utterly; curiously enough, he had the same kink. Spenser and Milton by a strange coincidence had it too (Surprised by Joy).

Lewis would actually come to edit a selection of MacDonald’s passages for an edifying anthology. This post includes a link for downloading a copy of George MacDonald: An Anthology.

This week I was reading one of MacDonald’s excellent essays, which appears in The Imagination and Other Essays. I intend to discuss some of his thoughts on age and writing soon. Although I am not an aficionado of poetry – despite having composed poetry from time to time, including quintains, I turned to another of MacDonald’s books.

On to His Poetry

I decided to follow up MacDonald’s brilliant essay with a dip into his poetry. Fortunately, Internet Archive allows you to freely download a complete copy of MacDonald’s Scotch Songs and Ballads, published in 1893. My conscience forces me, however, to provide a single caveat. Be forewarned that the tome is not suited for those intimidated by pronounced dialects.

Before looking at one of his poems in its entirety, allow me to share with you a passage from “The Waesome Carl” which I particularly enjoyed (due to its portrait of a preacher).

The minister wasna fit to pray

And lat alane to preach;

He nowther had the gift o’ grace

Nor yet the gift o’ speech!

He mind’t him o’ Balaäm’s ass,

Wi’ a differ we micht ken:

The Lord he opened the ass’s mou,

The minister opened’s ain!

He was a’ wrang, and a’ wrang,

And a’thegither a’ wrang;

There wasna a man aboot the toon

But was a’thegither a’ wrang!

The puir precentor couldna sing,

He gruntit like a swine . . .

Not that I claim able to decipher it all, but my impression is that it’s not especially flattering. It is definitely entertaining. And I humbly think I interpret it significantly more accurately than Google’s online translator, which provided the following version.

The minister was not fit to pray

And lat alane to preach;

He nowther had the gift o’ grace

Nor yet the gift o’ speech!

He mind’t him o’ Balaam’s ass,

Wi’ a differ we micht ken:

The Lord he opened the ass’s mou,

The minister opened his eyes!

He was a’ wrang, and a’ wrang,

And a’thegither a’wrang;

There was a man aboot the toon

But thegither was wrong!

The puir precentor couldna sing,

He grunted like a swine. . .

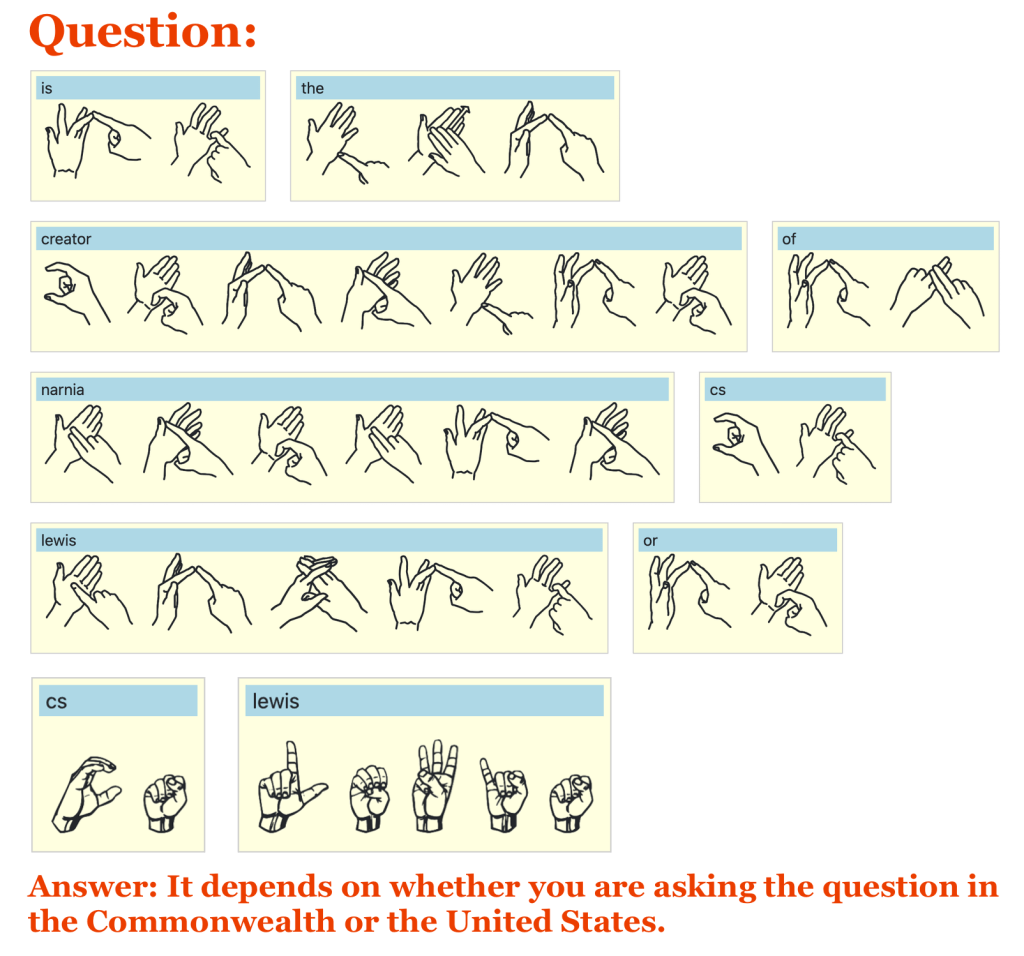

Using the Dictionars o the Scots Leid, you can make perfect sense of the words about which you may be uncertain. (Thank you, Scotland.)

Dialects are interesting things indeed. I will close with another of MacDonald’s poems. I submit it for (1) those who comprehend the dialect, (2) those who deem precious their Scottish ancestry, (3) those with an affinity for Connor MacLeod, and (4) those who simply enjoy a challenge.

I like ye weel upo Sundays, Nannie,

I’ yer goon and yer ribbons and a’;

But I like ye better on Mondays, Nannie,

Whan ye’re no sae buskit and braw.For whan we’re sittin sae douce, Nannie,

Wi’ the lave o’ the worshippin fowk,

That aneth the haly hoose, Nannie,

Ye micht hear a moudiwarp howk,It will come into my heid, Nannie,

O’ yer braws ye are thinkin a wee;

No alane o’ the Bible-seed, Nannie,

Nor the minister nor me!Syne hame athort the green, Nannie,

Ye gang wi’ a toss o’ yer chin;

And there walks a shadow atween ‘s, Nannie,

A dark ane though it be thin!But noo, whan I see ye gang, Nannie,

Eident at what’s to be dune,

Liltin a haiveless sang, Nannie,

I wud kiss yer verra shune!Wi’ yer silken net on yer hair, Nannie,

I’ yer bonnie blue petticoat,

Wi’ yer kin’ly arms a’ bare, Nannie,

On yer ilka motion I doat.For, oh, but ye’re canty and free, Nannie,

Airy o’ hert and o’ fit!

A star-beam glents frae yer ee, Nannie–

O’ yersel ye’re no thinkin a bit!Fillin the cogue frae the coo, Nannie,

Skimmin the yallow ream,

Pourin awa the het broo, Nannie,

Lichtin the lampie’s leme,Turnin or steppin alang, Nannie,

Liftin and layin doon,

Settin richt what’s aye gaein wrang, Nannie,

Yer motion’s baith dance and tune!I’ the hoose ye’re a licht and a law, Nannie,

A servan like him ‘at’s abune:

Oh, a woman’s bonniest o’ a’, Nannie,

Doin what maun be dune!Cled i’ yer Sunday claes, Nannie,

Fair kythe ye to mony an ee;

But cled i’ yer ilka-day’s, Nannie,

Ye draw the hert frae me!

Addendum:

For those interested in pursuing this linguistic subject, I just came across a delightful 1896 collection of works you can download for free. Legends of the Saints: in the Scottish Dialect of the Fourteenth Century is “edited from the unique manuscript in the University Library, Cambridge.”

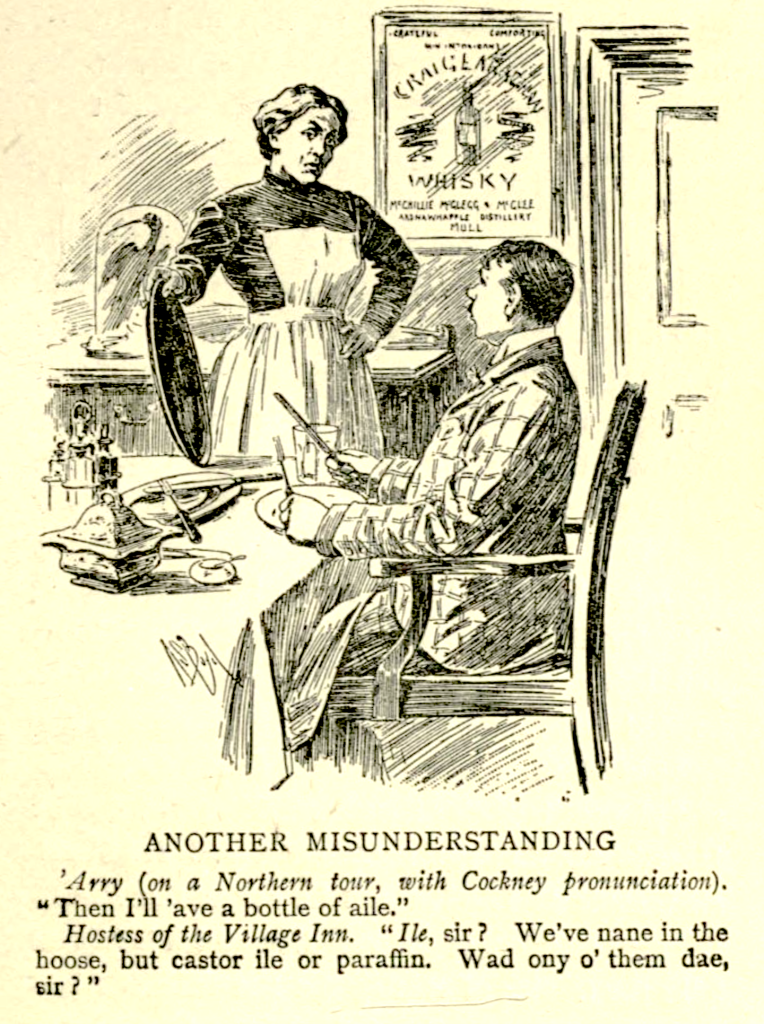

The cartoon above comes from Mr. Punch in the Highlands which was published “with 140 illustrations” more than a century ago. You can download your personal copy of humorous work at Internet Archive.