How is this for an odd New Year resolution? Getting a new tattoo—with a connection to the writings of C.S. Lewis.

I suppose I’m betraying my age here. Being a retired pastor, my body remains a totally uninked canvas. Not that I’ve never considered getting a tattoo. In fact, if I end up making a pilgrimage to Jerusalem before I journey to the New Jerusalem, I may still opt to get inked. In Jerusalem there is a tattooist whose family traces their art back for 700 years to when their Coptic family lived in Egypt.

Our ancestors used tattoos to mark Christian Copts with a small cross on the inside of the wrist to grant them access to churches . . and from a very young age (sometimes even a few months old) Christians would tattoo their children with the cross identifying them as Copts. . . .

One of the most famous of Christian types of tattoos, however, is still in use today—that of the pilgrimage tattoo. At least as early as the 1500s, visitors to the Holy Land . . . often acquired a Christian tattoo symbol to commemorate their visit, particularly the Jerusalem Cross.

In Bethlehem, another Christian tattooist practices his art “near the Church of the Nativity, offering pilgrims ink to permanently mark their visit.” He offers designs featuring scriptural texts in Hebrew and Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus.

Tattoos have a fascinating history, and it should be noted some people consider Torah prohibition to bar even religious tattoos. “You shall not make any cuts on your body for the dead or tattoo yourselves: I am the Lord” (Leviticus 19:28). However, most Christians* and increasing numbers of Jews do not agree that the passage forbids the current practice.

That doesn’t mean all tattoos are appropriate, of course. Most tattoos are innocuous. Some are humorous. A small number are actually witty. Yet some tattoos can be downright malevolent.

Like so many human activities, the significance of a tattoo depends in great part on the intention of the person asking for this permanent mark. For example, my wife and I approved of our son and his wife having their wedding rings tattooed in recognition of God’s desire⁑ that a marriage will last as long as both individuals live.

What has this to do with C.S. Lewis?

Precious few writers have penned more inspiring and enlightening words than Lewis, that great scholar of Oxford and Cambridge. Because of this, it should come as no surprise that there are many Lewis-inspired tattoos gracing bodies. There is even a website devoted to C.S. Lewis-inspired body ink.

I imagine that Lewis himself would regard this as quite peculiar. I don’t believe he had any tattoos of his own, but it’s quite possible his brother Warnie—a retired veteran of the Royal Army—may have sported one or more.

In 1932, Lewis wrote to Warnie about his recent walking trip. Warnie was his frequent companion, when he was not elsewhere deployed. In this fascinating piece of correspondence, Lewis described his most recent excursion. I include a lengthy excerpt (comprising the first half of the journey) not because of its single passing mention of tattoos. Rather, because of the portrait it paints of the young and vigorous scholar in the prime of life. If you would prefer to skip to the mention of inking, see the sixth paragraph.

Since last writing I have had my usual Easter walk. It was in every way an abnormal one. First of all, Harwood was to bring a new Anthroposophical Anthroposophical member (not very happily phrased!) and I was bringing a new Christian one to balance him, in the person of my ex-pupil Griffiths. Then Harwood and his satellite ratted, and the walk finally consisted of Beckett, Barfield, Griffiths, and me.

As Harwood never missed before, and Beckett seldom comes, and Griffiths was new, the atmosphere I usually look for on these jaunts was lacking. At least that is how I explain a sort of disappointment I have been feeling ever since. Then, owing to some affairs of Barfield’s, we had to alter at the last minute our idea of going to Wales, and start (of all places!) from Eastbourne instead.

All the same, I would not have you think it was a bad walk: it was rather like Hodge who, though nowhere in a competition of Johnsonian cats, was, you will remember, ‘a very fine cat, a very fine cat indeed.’

The first day we made Lewes, walking over the bare chalky South Downs all day. The country, except for an occasional gleam of the distant sea—we were avoiding the coast for fear of hikers—is almost exactly the same as the Berkshire downs or the higher parts of Salisbury Plain. The descent into Lewes offered a view of the kind I had hitherto seen only on posters—rounded hill with woods on the top, and one side quarried into a chalk cliff: sticking up dark and heavy against this a little town climbing up to a central Norman castle.

We had a very poor inn here, but I was fortunate in sharing a room with Griffiths who carried his asceticism so far as to fling off his eiderdown—greatly to my comfort. Next day we had a delicious morning—just such a day as downs are made for, with endless round green slopes in the sunshine, crossed by cloud shadows. The landscape was less like the Plain now. The sides of the hill—we were on a ridgeway—were steep and wooded, giving rather the same effect as the narrower parts of Malvern hills beyond the Wych.

We had a fine outlook over variegated blue country to the North Downs. After we had dropped into a village for lunch and climbed onto the ridge again for the afternoon, our troubles began. The sun disappeared: an icy wind took us in the flank: and soon there came a torrent of the sort of rain that feels as if one’s face were being tattooed and turns the mackintosh on the weather side into a sort of wet suit of tights.

At the same time Griffiths began to show his teeth (as I learned afterwards) having engaged Barfield in a metaphysico-religious conversation of such appalling severity and egotism that it included the speaker’s life history and a statement that most of us were infallibly damned. As Beckett and I, half a mile ahead, looked back over that rain beaten ridgeway we could always see the figures in close discussion. Griffiths very tall, thin, high-shouldered, stickless, with enormous pack: arrayed in perfectly cylindrical knickerbockers, very tight in the crutch. Barfield, as you know, with that peculiarly blowsy air, and an ever more expressive droop and shuffle.

For two mortal hours we walked nearly blind in the rain, our shoes full of water, and finally limped into the ill omened village of Bramber. Here, as we crowded to the fire in our inn, I tried to make room for us by shoving back a little miniature billiard table which stood in our way.

I was in that state of mind in which I discovered without the least surprise, a moment too late, that it was only a board supported on trestles. The trestles, of course, collapsed, and the board crashed to the ground. Slate broken right across. I haven’t had the bill yet, but I suppose it will equal the whole expences of the tour.

Wouldn’t it have been amazing to join C.S. Lewis on one of these walking trips? A Lewisian tattoo is no substitute, to be sure, but I imagine it does offer certain people a sense of connection to the great author. Perhaps, if I were a younger man . . .

* Two recent converts to Christianity, Kanye West and Justin Bieber have made public their recent religious additions to their vast tattoo collections.

⁑ As Jesus said, “So they are no longer two but one flesh. What therefore God has joined together, let not man separate.”

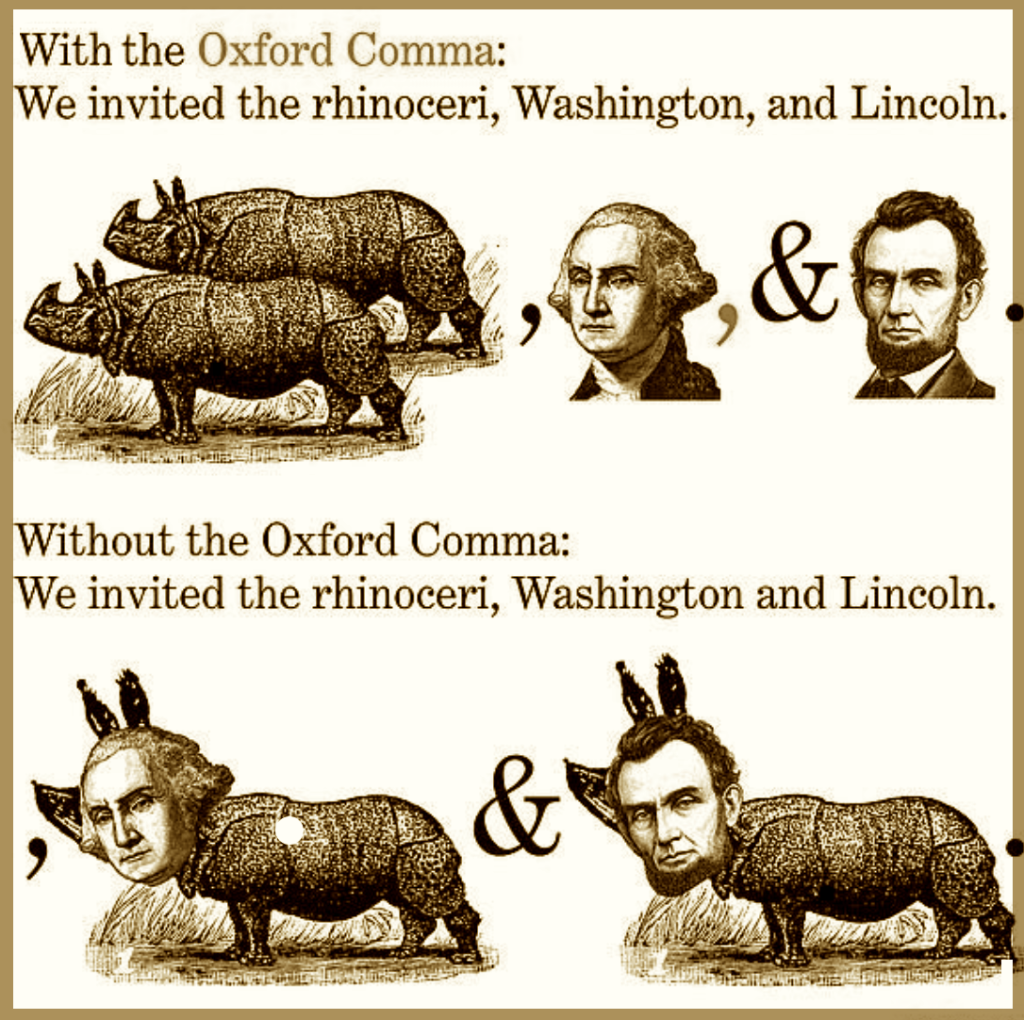

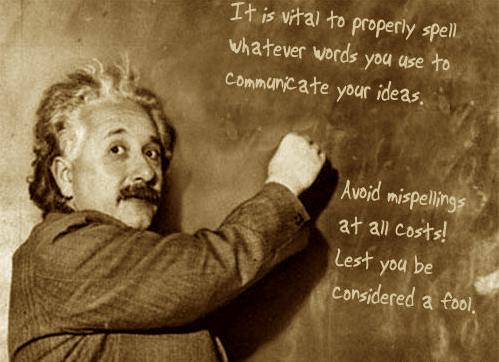

The motivational poster above was created by Mere Inkling, and represents only an infinitesimal number of the misspelled tattoos adorning human bodies. What a travesty . . . one that may have been prevented by remaining sober. The tattoo below, on the other hand, strikes me (being a writer) as quite clever.

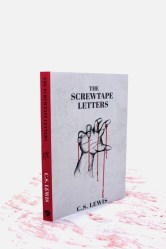

I wanted to convey an accurate image of the book, while also allowing for some ambiguity so the reader could project their own meaning onto the cover. C.S. Lewis books are traditionally marketed toward Christian audiences, and often have light-hearted covers. . . . I wanted the books to appeal to a non-Christian audience, and I wanted the books to have a gritty and more emotional feeling, while also alluding to the extraordinary qualities inside the book.

I wanted to convey an accurate image of the book, while also allowing for some ambiguity so the reader could project their own meaning onto the cover. C.S. Lewis books are traditionally marketed toward Christian audiences, and often have light-hearted covers. . . . I wanted the books to appeal to a non-Christian audience, and I wanted the books to have a gritty and more emotional feeling, while also alluding to the extraordinary qualities inside the book.