Do you have trouble coming up with ideas for your poems or stories? How about starting with an interesting collection of words and winnowing them down to a creation of your own? Read on to learn more about a simple process.

A few years ago a fellow pastor told me he could write, even short articles like blog posts. Since he had successfully completed a challenging graduate program, I was a bit shocked at this disclosure. “The problem,” he said, “is that I just can’t come up with any ideas for what to write.”

I had two reactions. First, I was amazed, since I can’t get through a day without encountering at least a handful of observations that beg to be explored. Second, I wondered just what sort of sermons his congregation was exposed to, if creative imagery and fresh ways of expressing God’s timeless truths were not coming from their pulpit.

One of the ways I attempt to improve my own writing is by stretching. In my personal shorthand, this refers to engaging in new forms of writing. Principally that means voluntarily jumping into sometimes ominous literary waters. I stretch myself by humbly engaging in genres which I may, in all honesty, find intimidating.

For example, occasionally, when bored with outlining books that may never get written, I’ll just scribble out some “impromptu verse.” Some of it turns out rather decent. (You’ll notice I didn’t say “excellent.”)

Blacking Out Words to Compose New Literature

I had heard of Blackout Poetry before, but never attempted to “write” any. Actually, it seems to me that “decompose” might be a more accurate word for this type of creating. Although most commonly used to create brief works, such as poetry, the concept can be used for narratives as well.

If you are unfamiliar with the process, you may enjoy the following, introductory articles.

“Teach Kids Art” explains the basic process and then adds some visual artistry to the mix.

Blackout Poetry is a form of “found poetry” where you select words that catch your interest from a newspaper, book, or other printed text – along with a few additional words to make it flow. Then you “redact” all the words you don’t want. This is often (but not always) done with a black marker, hence the name “blackout poetry.” Your chosen words will form a new message, giving the text a whole new meaning.

Take your Blackout Poetry a step further by adding patterns, designs, or a drawing to the areas you’re “redacting.” For example, instead of just filling in around your chosen words with solid black, you could create a drawing or design that relates to your poem. Just as with any illustration, your art should support the remaining text and add to its meaning.

“Looking Beyond the Comfort Zone” discusses a reservation many will have about pursuing blackout writing.

I really wanted to give it a try. There were however a few obstacles to overcome. First was my ingrained prohibition of defacing books. Although I owned a highlighter in college I rarely used it. It seemed wrong. . . .

Secondly the blackout poetry requires making the page unreadable for the original words. I felt a lot of good old-fashioned guilt in the prospect of destroying someone’s story. Lastly, I didn’t have any books that I felt so little regard for that I could take a sharpie marker to the pages.

I, personally, have eliminated the second reservation by scanning an image of each experimental page and blacking words out digitally. It would be just as simple to print out such an image, or simply use a copier with a physical book, if you prefer to create your work manually. My method eliminates another potential problem for bibliophiles, the damage often caused to a book’s spine when attempting to flatten the page for copying.

“5 Tips for Creating Blackout Poetry” claims the genre is “the best cure for writer’s block.” To enhance miscellany, they suggest “when picking an article to use, it’s best not to read it too closely.”

That way, you aren’t overly influenced by the author’s original work and you can create something uniquely your own.

This suggestion will certainly be beneficial in liberating the creativity of many writers. For my own purposes, I disregarded this advice, since I intentionally desired to use words by or about particular authors. I honestly want the original context to be in my mind during the metamorphosis.

A final source, “A blackout poem on the Trinity,” reveals how a writer in Europe found inspiration in the writings of C.S. Lewis for her own poem about the Trinity. Check out Christine’s verse at the link above.

This is the first time I’ve tried a blackout poem. They work by taking a page of text and then blacking it out until only the remaining words give you the poem.

In the end, I chose “It all began with a picture . . .” published in the Junior Section of The Radio Times on 15 July 1960. It’s a short and sweet description of how Lewis was inspired to write the Narnia stories.

My Initial Attempts

As I mentioned above, I scanned printed pages that you can easily find at Internet Archives, Google Books, Project Gutenberg and various other sites.

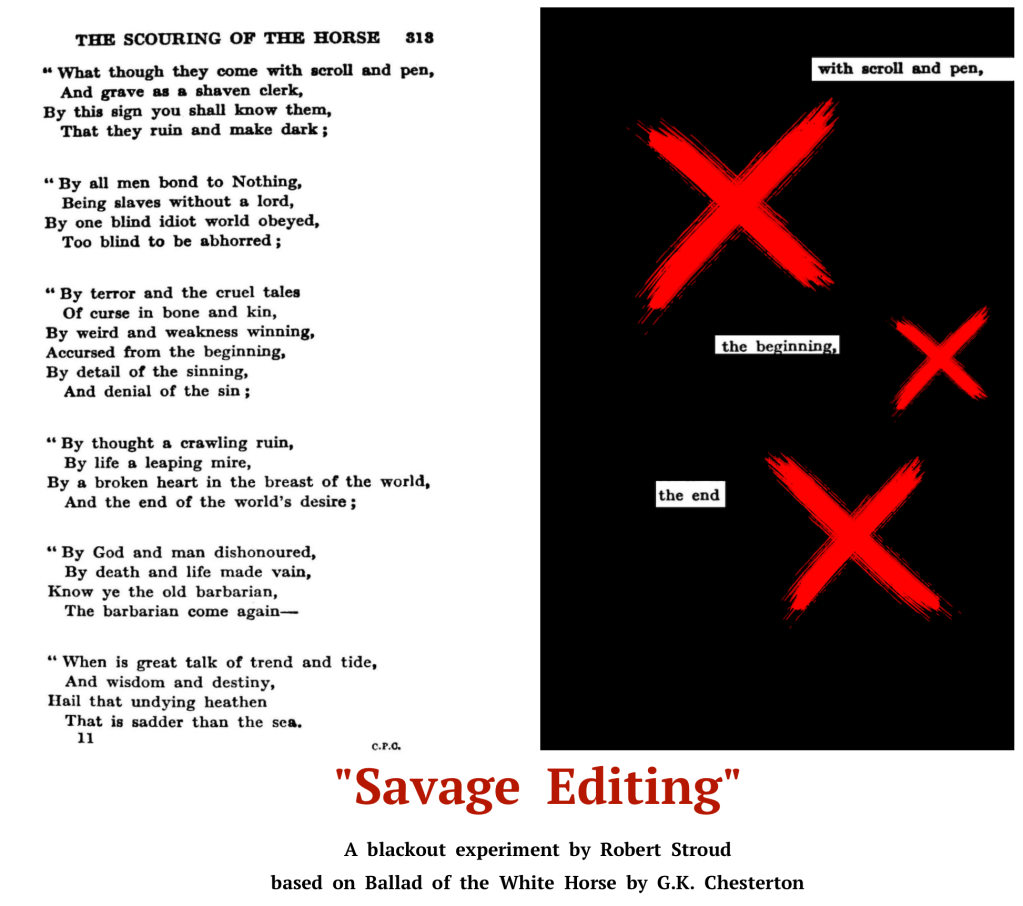

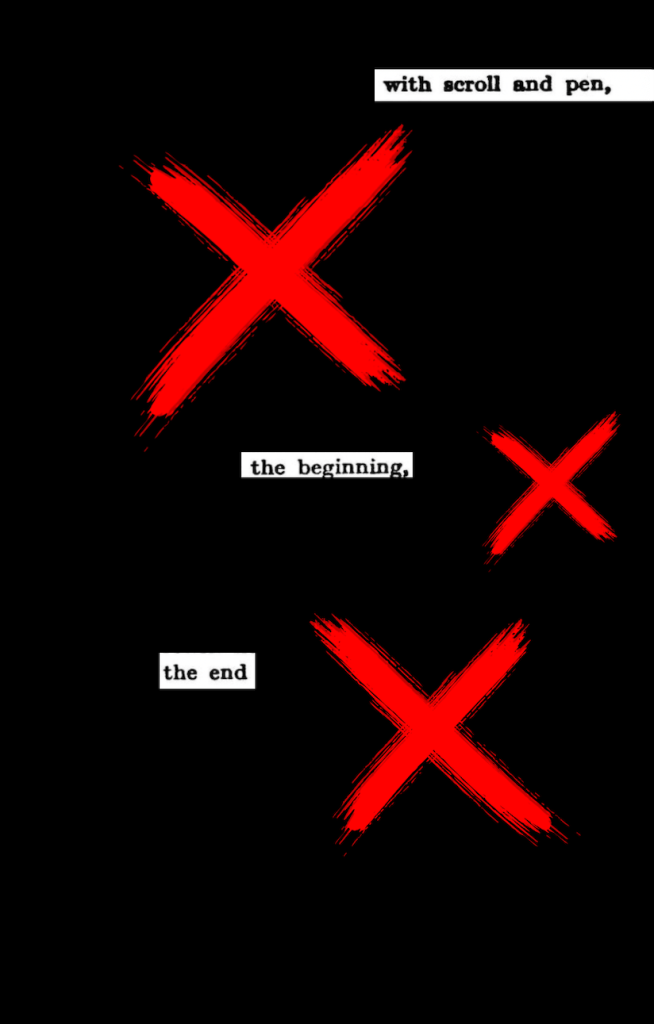

I did not attempt to write poetry. Rather, I used each page to write a brief, new narrative. Of my first three efforts, I was most pleased with “Savage Editing,” displayed above. Below, I will place it beside the original page, from The Collected Poems Of G.K. Chesterton.

I’ll close by passing on to you the experience of the author who composed an ode on the Trinity, using an article about C.S. Lewis. My guess is that you too – should you be so bold as to attempt writing your own blackout works – will experience a similar satisfaction.

It’s hard being constrained by the page of text in front of you. The more you black out, the less you say; but the less you black out, the less impact each word has. It’s a game of compromise, striking the balance between being artistic and understandable.

But I think the end result is a celebration of both Lewis’ work and the Trinity.

The illustration below shows my blackout, which I entitled “Savage Editing,” beside the original page, which includes a portion of “The Scouring of the Horse,” from The Collected Poems Of G.K. Chesterton. “The Scouring” is the final book in Chesterton’s Ballad of the White Horse.