Everyone experiences some anxiety, but it is only considered a “disorder” when it negatively affects one’s quality of life. Sadly, that level has been reached by nearly twenty percent of Americans.

An estimated 19.1% of U.S. adults had an anxiety disorder in the past year. Past year prevalence of any anxiety disorder was higher for females (23.4%) than for males (14.3%). An estimated 31.1% of U.S. adults experience any anxiety disorder at some time in their lives (National Institute of Mental Health).

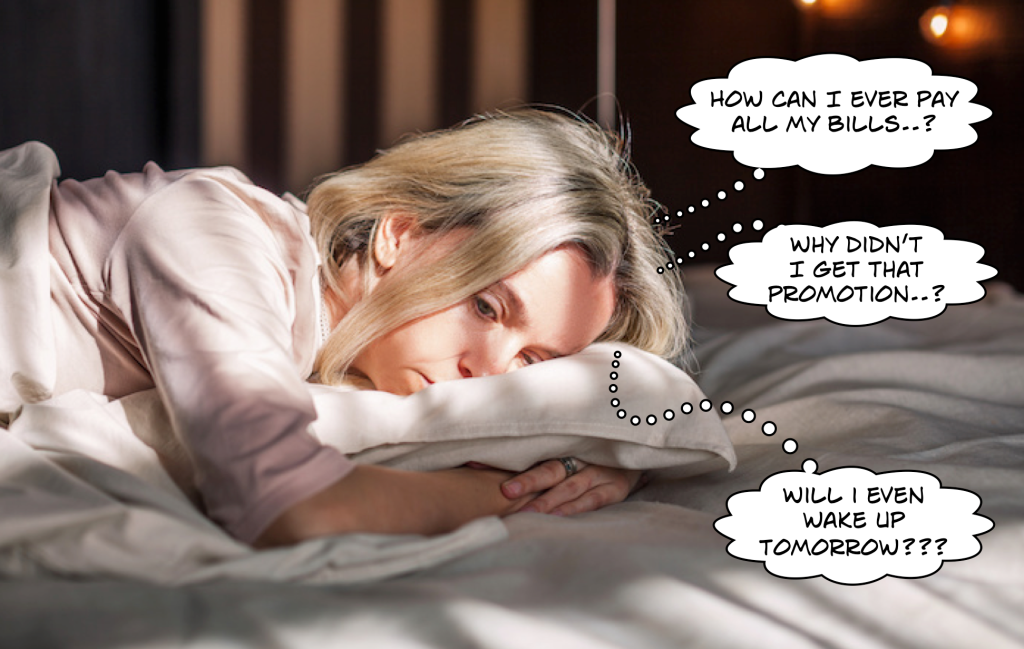

As one specialist puts it, “there’s a very strong, well-documented bidirectional link between sleep and mental health issues like anxiety.” And it can become a vicious cycle: “If you have poor sleep, you’re at greater risk of a mental health issue. And if you have a mental health condition like anxiety, you’re more likely to develop a sleep disorder.”

Those “disorder” figures are only for anxiety passing a problematic threshold. Feeling some anxiety is a normal part of life, even for Christians. (Fortunately, however, we have an Intercessor who alleviates anxiety in our fallen lives.)

Do not be anxious about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus (Philippians 4:6-7).

The universality of experiencing anxiety is evidenced by the etymology of the word itself. The Latin anxius simply means troubled or worried (i.e. anxious).

In his classic Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, C.S. Lewis addresses the negativity associated with being anxious, that actually worsens the problem.

Some people feel guilty about their anxieties and regard them as a defect of faith. I don’t agree at all. They are afflictions, not sins. Like all afflictions, they are, if we can so take them, our share in the Passion of Christ.

So, if most of us admit to experiencing some worry, the question posed by a recent article in TIME is whether the anxiety peaks at night. While not universal, “research has long suggested that, for many people, anxiety symptoms spike and mental health otherwise suffers at night.” While the piece cited several reasons, it left out two causes I consider self-evident.

The article points to studies about how substance abuse and suicidal behavior rise “after midnight,” and how “the racing thoughts that plague many anxiety sufferers are at their worst in the evening.” While I didn’t read the linked research, these statements are simply descriptive of the problem.

As for identified causes, the studies point to our diminished ability to “regulate emotions” as we tire. The issue of isolation is noted as a second factor, since “the rest of the world is asleep.” Further, the lack of daytime distractions may set the stage for “runaway anxiety” as we ponder the “what ifs” of the future. Another logical finding is that anxiety builds as we sleep poorly because we are worrying, which makes us prone to becoming even more anxious.

So What are the Uncited Factors?

First, it seems to me that the darkness of night itself is a major consideration. Since primordial times, night was foreboding. Sharpened wooden or stone-tipped weapons offered little enough defense when we could see predators (beast or human). Our ability to make fires and light candles ignited trifling circles of light that barely penetrated the shadows.

The uncertainty about what lurks in those shadows remains with us today. Just consider how quickly chaos can arise when there are power outages and the “protection” offered by light instantly evaporates.

Related to this is the simple fact that bad things (like crimes), increase during darkness. While many unlawful acts certainly occur during daylight hours, many of the most violent and heinous crimes, such as rape, occur after the sun sets. You can compare many variables at this website.

It is simply common sense to recognize we are more vulnerable to violent attack when darkness masks attackers’ identities. The Book of Job vividly describes this lawless predilection.

There are those who rebel against the light,

are not acquainted with its ways,

and do not stay in its paths.

The murderer rises before it is light,

that he may kill the poor and needy,

in the night he is like a thief.

The eye of the adulterer also waits for the twilight,

saying, ‘No eye will see me;’

he veils his face.

In the dark they dig through houses;

by day they shut themselves up;

they do not know the light.

For deep darkness is morning to all of them;

for they are friends with the terrors of deep darkness (Job 24:13-17).

While the increased criminal behavior during darkness may have been omitted due to the tacit acknowledgment that it is a factor, my second observation was quite possibly overlooked due to ignorance or prejudice.

The Spiritual Consideration

I am convinced there is a spiritual component to our wariness related to darkness. Even those secularists dismissive of this reality would likely recognize this as a common perception. After all, it is no accident that stories (ancient and modern) depict wicked gatherings and malevolent supernatural events as taking place primarily at night.

The Scriptures discuss this Light/Dark dichotomy extensively. One of the clearest examples comes in the explanation for why sinful people choose to reject the coming of Christ.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. . . . In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. . . .

[Jesus said] “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. Whoever believes in him is not condemned . . . the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil.

For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed. But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his works have been carried out in God” (John 1–3, selected verses).

Because darkness helps mask unsavory behavior, author Dave Jenkins advises people to be vigilant regarding their own temptations. He shares his personal story attesting to his contention that “night time for many men and women is danger time.”

This certainly is not God’s desire for any of us. As “The Godliness of a Good Night’s Sleep” concludes, “sleep, it seems, is no fallen necessity, nor merely a fleshly temptation, but a divine gift.”

In The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis’ brilliant exploration of diabolic strategies, the senior demon advises his protégé, how to rob humanity of this blessing.

There is nothing like suspense and anxiety for barricading a human’s mind against the Enemy. He wants men to be concerned with what they do; our business is to keep them thinking about what will happen to them.

But fortunately, humanity’s first Enemy does not have the final say in the matter.

Even During the Darkest Night

We need never be alone nor despair in the night. In fact, even the trials posed by anxiety can become a pathway to a more intimate reliance and relationship with God.

Perhaps most famously, this concept has been associated in Christian circles with “Dark Night of the Soul,” a poem written by Saint John of the Cross in the sixteenth century. In an upcoming post, we will consider John’s life and the controversial actions which followed his death.