Recently I read about an African Christian who was raised in a family that practiced ancestral worship. His grandfather was considered a witchdoctor, and it was expected that this young man would assume his duties.

The only problem is that when I initially viewed the passage, I read that his grandfather was a whichdoctor.

My once 20/20 vision is long gone. I still read without glasses (for the most part), but when I have yet to wash the sleep from my eyes, I encounter some surprising words.

“Whichdoctor” actually made some sense. I acknowledge it hasn’t been an English word (until now) but is so clear and so utilitarian that it cries out for recognition.

Whichdoctor: An interrogative used when attempting to ascertain which physician’s attention an individual should be seeking. Especially useful in a hospital setting with numerous specialists. As in: Whichdoctor should I talk to, the podiatrist, the pediatrician, the pulmonologist, the psychiatrist, the pathologist, or the proctologist?

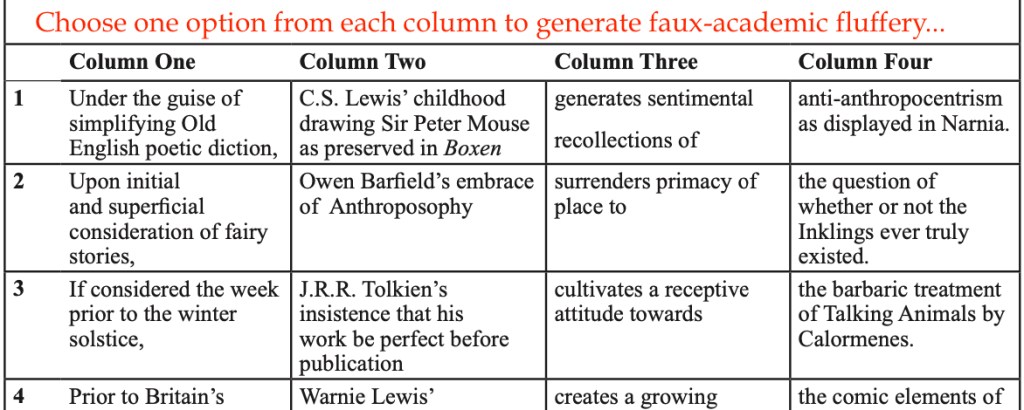

Last year I posted a column entitled “Create a Word Today.” It was inspired by an article I cited about making up useful words with pertinent definitions. I included 22 examples in my first column. They touched on a variety of subjects.

Mannekin: A boring, sedentary relative, who rarely rises from the couch.

Purrification: The activity of forgiveness and restoration that occurs when any cat makes a sincere confession of its sins.

Several were ecclesiastical in flavor.

Cathedroll: A large church led by a senior minister given to quaint and unintentionally comic humor.

Concupiscents: Hollywood’s obsession with including graphic sexual themes in all of their productions, resulting in the selling of their souls for pennies on the dollar.

And some related to the field of writing.

Manuskipped: The sad condition when the article or book into which you poured your blood, sweat and tears has been tossed into a slush pile to lie forgotten.

Proofreaper: Someone you invited to read your manuscript for misspellings who advises you to delete entire sections of your precious creation.

If you’re curious, there are 16 additional words included in the original post linked above.

So, allow me to offer here a few recent efforts, inspired by the misreading I referred to at the top of the page. How about 22 more?

But, before that, let’s look at a passage from C.S. Lewis’ autobiography, Surprised by Joy. As a person who has always appreciated a good vocabulary – and who is blessed to have grandchildren who are articulate beyond their years – I am saddened by Lewis’ youthful experience.

Reading much and mixing little with children of my own age, I had, before I went to school, developed a vocabulary which must (I now see) have sounded very funny from the lips of a chubby urchin in an Eton jacket.

When I brought out my “long words” adults not unnaturally thought I was showing off. In this they were quite mistaken. I used the only words I knew.

The position was indeed the exact reverse of what they supposed; my pride would have been gratified by using such schoolboy slang as I possessed, not at all by using the bookish language which (inevitably in my circumstances) came naturally to my tongue.

And there were not lacking adults who would egg me on with feigned interest and feigned seriousness – on and on till the moment at which I suddenly knew I was being laughed at.

Then, of course, my mortification was intense; and after one or two such experiences I made it a rigid rule that at “social functions” (as I secretly called them) I must never on any account speak of any subject in which I felt the slightest interest nor in any words that naturally occurred to me. And I kept my rule only too well . . .

Hooplaw: The two, vastly different legal disciplines dealing with (1) basketball contracts, and (2) litigation related to injuries caused by overly excited commotion.

Interdisciplinairy: The entire field of specialty studies related to the atmosphere.

Marvelouse: A creep or cad who considers himself something quite extraordinary.

Atrofee: The medical bills associated with the care of patients suffering an enduring coma.

Predilicktion: A preference for the sensation of taste over the other four basic human means of perceiving the world around us.

Ammunishun: The attitude of some activists seeking to restrict Second Amendment rights.

Megalowmaniac: The true stature of power hungry narcissists.

Gratuitruss: The unnecessary wear of a device to restrain a nonexistent hernia.

Calumknee: Malicious misrepresentations of political figures who frequently stumble.

Misscalibration: The awkward occasion when footwear retailers suggest to a young lady try on size 20 Air Jordans.

Patriought: The noble, often self-sacrificial, behavior of citizens who truly love their country.

Hypnothetically: The wide range of potentially embarrassing acts a person might be directed to perform under the influence of mesmerism.

Enlightenmint: The experience of achieve a spiritual pinnacle, accompanied by an aromatic scent.

Raspewtin: What Russia’s last Tsar should have done to Grigori.

Canonball: An elegant celebration lacking minuets, due the participants’ vows of celibacy, but not lacking in a wide selection of vinted and distilled beverages.

Immaculatte: A perfectly balanced beverage prepared by one of the world’s finest baristas.

Telegraft: Crimes committed over the phone by telemarketers, or via the airwaves and internet by televangelists.

Archietype: Ideas and symbols that recur in stories from many cultures and eras which bear a clear likeness to Archibald Andrews, who was often accompanied by his companion Jughead.

Syruptitious: The practice of slipping secrets past the unsuspecting by applying sticky sentimentality to one’s words.

Youphemism: The substitution of a mild or neutral description of someone to replace what you truly think of them.

Boulebard: The landscaped avenues of Stratford-upon-Avon by William Shakespeare.

Hagographer: An author who prefers to write the biographies of harpies rather than saints.

Admittedly, these words are not all top tier, but I challenge you to do better. If you have one or two winners, please cite them in the comments below. Oh, I just thought of another:

Religioscity: The religious devotion expressed by the residents of an urban environment.

Now I need to think about something else so I’ll be able to sleep tonight without jumbled word running through my mind.

As the sainted C.S. Lewis once described some troubled days in a boarding school while a youth:

Consciousness itself was becoming the supreme evil; sleep, the prime good. To lie down, to be out of the sound of voices, to pretend and grimace and evade and slink no more, that was the object of all desire—if only there were not another morning ahead—if only sleep could last for ever! (Surprised by Joy)