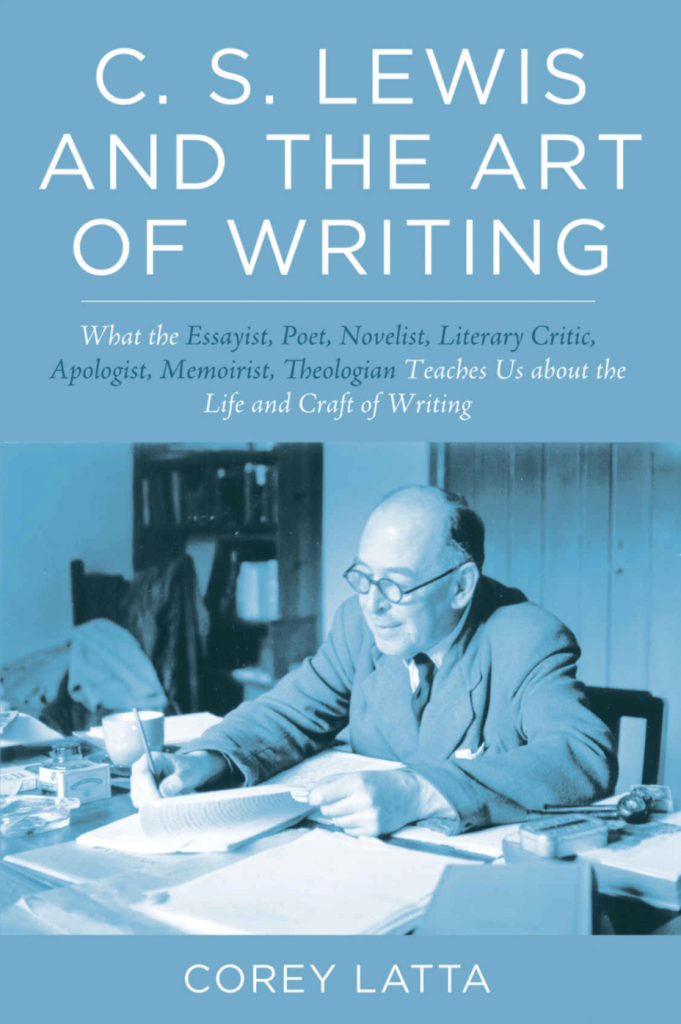

Have your feelings about particular authors changed over time? C.S. Lewis’ attitude toward the work of prolific novelist Naomi Mitchison illustrates this type of progression.

Mitchison’s work possesses a direct link to another Oxford Inkling – J.R.R. Tolkien – whose Fellowship of the Ring she read in proof and favorably reviewed. Brenton Dickieson provides a priceless letter written by Tolkien to Mitchison in 1954.

Naomi Mary Margaret Mitchison was a Scottish novelist who lived more than a century (1897 – 1999). She penned more than ninety books, primarily historical fiction, and including science fiction.

With the outbreak of the First World War, Mitchison joined a Voluntary Air Detachment in a London hospital. (Other familiar women who served in a VAD included Agatha Christie and Amelia Earhart.)

Politically she identified as a Socialist. She was sufficiently leftist that George Orwell regarded her as unsuited for writing anti-Soviet materials for the United Kingdom during the Cold War.

Mitchison’s brother, J.B.S. Haldane, did not equivocate on his radical views, announcing his position as a Marxist. He was a scientist and his atheism brought him into serious disagreement with the Christian views of C.S. Lewis. (I will devote my next post to that interaction.)

Coincidentally, artist Pauline Baynes (who also worked with C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien), provided the illustrations for at least one of Mitchison’s children’s books, Graeme and the Dragon. This quick review offers a concise synopsis and discussion of “the charming illustrations [which] go a long way toward making this a fun read.”

An additional coincidence: the same year Lewis published The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Mitchison also published a fantasy novel for children. The Big House involves time travel and some occultic themes associated with Halloween, etc.

For a thorough synopsis of The Big House and comparison to Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia, check out this essay from the University of Glasgow. (That reviewer’s preference is clearly for Mitchison’s more complex approach with its themes related to class struggle.)

C.S. Lewis’ Perspective on Naomi Mitchison

I cannot locate any mention of C.S. Lewis by Mitchison, but he did mention her in passing in several pieces of correspondence. In essence, he praised her skill, but was put off by her graphic use of violent imagery.

In a 1932 letter to Arthur Greeves, he writes:

I thought we had talked about Naomi Mitchison before. I have only read one (Black Sparta) and I certainly agree that it ‘holds’ one: indeed I don’t know any historical fiction that is so astonishingly vivid and, on the whole, so true.

I also thought it astonishing how, despite the grimness, she got such an air of beauty–almost dazzling beauty–into it. As to the cruelties, I think her obvious relish is morally wicked, but hardly an artistic fault for she could hardly get some of her effects without it.

But it is, in Black Sparta, a historical falsehood: not that the things she describes did not probably happen in Greece, but that they were not typical–the Greeks being, no doubt, cruel by modern standards, but, by the standards of that age, extremely humane.

She gives you the impression that the cruelty was essentially Greek, whereas it was precisely the opposite. That is, she is unfair as I should be unfair if I wrote a book about some man whose chief characteristic was that he was the tallest of the pigmies, and kept on reminding the reader that he was very short. I should be telling the truth (for of course he would be short by our standards) but missing the real point about the man–viz: that he was, by the standards of his own race, a giant.

Still, she is a wonderful writer and I fully intend to read more of her when I have a chance.

C.S. Lewis echoed his concern in a 1942 letter to another of his regular correspondents, Sister Penelope. “I gave up Naomi Mitchison some time ago because of her dwelling on scenes of cruelty. But I recognise real imagination and a sort of beauty in the writing.”

In 1951, C.S. Lewis congratulated author Idrisyn Oliver Evans (1894–1977) on the publication of The Coming of a King; A Story of the Stone Age. Ironically, speculative fiction set in this ancient era, referred to as “Prehistoric SF,” was also the setting of works such as H.G. Wells’ Story of the Stone Age series, which you can read here. Naomi Mitchison also dabbled in the prehistoric field. Lewis wrote to Evans:

I congratulate you. And I think it is a great thing to put that idea of the Stone Age – which is at least as likely to be the true one – into boys’ heads instead of Well’s or Naomi Mitchison’s. It’s all good. The marriage customs are amusing . . . I hope it will be a great success.

In 1959, C.S. Lewis provided some wise counsel to a young, aspiring author. The American student was contemplating a volume about the Roman subjugation of Gaul, which Lewis encouraged.

A story about Caesar in Gaul sounds very promising. Have you read Naomi Mitchison’s The Conquered? And if not, I wonder should you? It might be too strong an influence if you did (at any rate until your own book is nearly finished). On the other hand, you may need to read it in order to avoid being at any point too like it without knowing you are doing so.

I don’t know what one should read on Gaul. Apart from archaeological finds (Torques and all that) I suppose Caesar himself is our chief evidence? He will be great fun and I hope you will enjoy yourself thoroughly.

Which side will you be on? I’m all for the Gauls myself and I hate all conquerors. But I never knew a woman who was not all for Caesar – just as they were in his life-time.

C.S. Lewis’ most significant mention of Naomi Mitchison occurs in his brief 1943 essay, “Equality.”

It delivers a brilliant discussion of the subject, one that merits full reading. He commends one of Mitchison’s insights into inequality – although, ironically, she relates it to eroticism.* (You must read it in full context to understand how it supports his independent argument.)

This last point needs a little plain speaking. Men have so horribly abused their power over women in the past that to wives, of all people, equality is in danger of appearing as an ideal. But Mrs. Naomi Mitchison has laid her finger on the real point. Have as much equality as you please – the more the better – in our marriage laws, but at some level consent to inequality, nay, delight in inequality, is an erotic necessity.

Mrs. Mitchison [in The Home and a Changing Civilization] speaks of women so fostered on a defiant idea of equality that the mere sensation of the male embrace rouses an undercurrent of resentment. Marriages are thus shipwrecked.

A final reference to Mitchison brings us back around to my early note that she reviewed Fellowship of the Ring. C.S. Lewis refers to her review in his own, suggesting that she has not gone quite far enough in her praise.

Nothing quite like it was ever done before. ‘One takes it,’ says Naomi Mitchison, ‘as seriously as Malory.’ But then the ineluctable sense of reality which we feel in the Morte d’Arthur comes largely from the great weight of other men’s work built up century by century, which has gone into it.

The utterly new achievement of Professor Tolkien is that he carries a comparable sense of reality unaided. Probably no book yet written in the world is quite such a radical instance of what its author has elsewhere called ‘sub-creation.’

Sadly, Naomi Mitchison was less enamored with the subsequent volumes in The Lord of the Rings . . . but this post has already condensed more than enough information.

* An article in Michigan Feminist Studies notes how Naomi Mitchison’s recurrent references to sexual themes distracted from broader matters throughout her literary career.

Despite Mitichison’s attempts to move the discussion of her body of work from the salacious, it is the frank and open inclusion of sexuality that continues to intrigue her critics and reviewers. Racy, heated passages of Mitchison’s historical novels inspired comment from poet W.H. Auden in the 1930s (“Monstrous Sex: The Erotic in Naomi Mitchison’s Science Fiction”).

The essay’s thesis is what one might expect in a journal devoted to contemporary feminism.

I intend to demonstrate that the ribald sexuality of Mitchison’s work registers as more than merely provocative. Sexual encounters between female characters and aliens, as well as those between women, threaten an imperialising capitalism that dictates who may be loved in a gendered, racialised order.