People who are wise understand that not all forms of “love” are healthy. That’s obvious with the epidemic of faux love in today’s “hookup culture.”

But even in genuine relationships, such as families, what passes for “love” can become twisted. Even the best of motives can blind us to what’s really best for our children. This sad irony is on my mind right now, since it recently struck close to home.

The title of this post suggests that just as there is a healthy version of family love, there can also be subtle corruptions of that virtue.

Parenting is complicated. We love our children, but if we make “happiness” the primary goal we are missing the mark. This pursuit of what is more often “pleasure” than genuine joy, usually devolves into letting kids do whatever they want. Some people parent this way.

Others are willing to pay the price of helping their children learn the lessons that will lead to a truly meaningful and fulfilling life. This is love. Children raised with the first objective often end up pursuing their appetites. They seldom accomplish much in life and rarely look beyond their own desires, to see the needs of others.

One prominent organization supporting the families of addicts shares the following epiphany.

When I first came to Al‑Anon, I spent a great deal of time wrestling with the term, “enabling.” I am a mother. Surely a mother’s role is to enable her children, is it not? It has been a struggle to understand, let alone accept, that the behavior I viewed as that of a good mother was actually unhealthy!

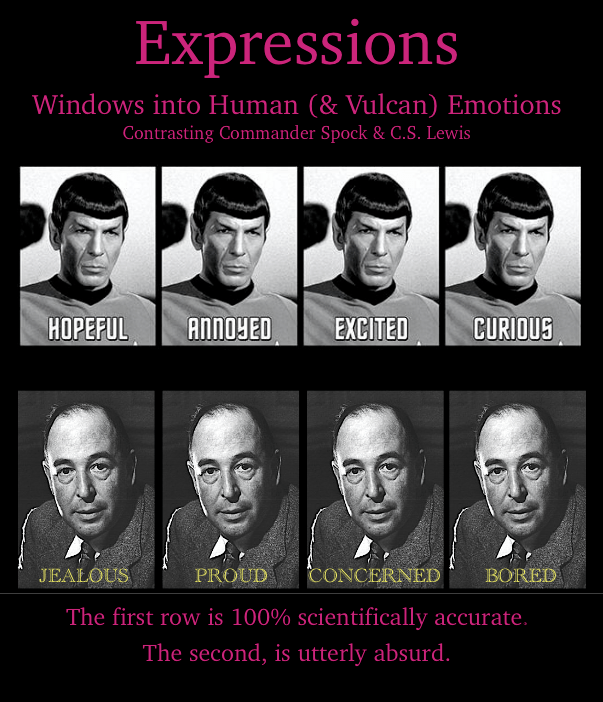

In his brilliant book, The Four Loves, C.S. Lewis describes how this unbalanced approach can be based in love, but results in unintended consequences.

The maternal instinct . . . is a Gift-love, but one that needs to give; therefore needs to be needed. But the proper aim of giving is to put the recipient in a state where he no longer needs our gift.

We feed children in order that they may soon be able to feed themselves; we teach them in order that they may soon not need our teaching.

Thus a heavy task is laid upon this Gift-love. It must work towards its own abdication. We must aim at making ourselves superfluous. The hour when we can say “They need me no longer” should be our reward.

But the instinct, simply in its own nature, has no power to fulfil this law. The instinct desires the good of its object, but not simply; only the good it can itself give. A much higher love – a love which desires the good of the object as such, from whatever source that good comes – must step in and help or tame the instinct before it can make the abdication.

The internationally recognized Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation offers an article on the subject entitled “Five Most Common Trademarks of Codependent and Enabling Relationships.”

The concept of codependency and enabling sounds simple and straight forward – doing for a loved one what they can and should do for themselves – but it can be incredibly difficult to tell the difference between supporting and enabling a loved one.

So what’s the difference? After all, enablers want to help their loved one, too, and codependency might feel like healthy support. But enabling allows the status quo – drinking or using drugs – to continue, whereas healthy support encourages a person to address their addiction and all of its consequences.

In contrast to this indulgent version of parenting, good parents are able to say “no” to their children, when it is necessary or appropriate. Teaching healthy behavioral boundaries early on teaches kids to make their own, healthy, decisions. Letting them take shortcuts and lie leads to disaster.

God’s divine love is inexhaustible. But God’s approval and blessing are linked to the choices we make. He does not commend self-destructive actions. He still loves, but he makes quite clear the life he desires for his children and the alternative path that leads to Death. God does not prevaricate. God does not hesitate to say “no.”

In the Book of Hebrews, the writer elaborates on this truth – that discipline (not to be confused with anger or punishment) is an evidence of genuine love.

Have you forgotten the exhortation that addresses you as sons? “My son, do not regard lightly the discipline of the Lord, nor be weary when reproved by him. For the Lord disciplines the one he loves, and chastises every son whom he receives.”

It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons. For what son is there whom his father does not discipline? If you are left without discipline, in which all have participated, then you are illegitimate children and not sons.

Besides this, we have had earthly fathers who disciplined us and we respected them. Shall we not much more be subject to the Father of spirits and live? For they disciplined us for a short time as it seemed best to them, but he disciplines us for our good, that we may share his holiness.

For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant, but later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it (Hebrews 12).

Parental Love in Lewis’ Fiction

C.S. Lewis’ classic The Great Divorce creatively illuminates errors that can come between each of us and God’s desire to bless and redeem us, and to usher us into his heavenly presence. In an “encounter” which shows how something as wonderful as familial affection can be perverted into a grotesque distortion of true love.

You should read the entire account in Lewis’ book, but hopefully the selection below will illustrate his insight.

One of the most painful meetings we witnessed was between a woman’s Ghost and a Bright Spirit who had apparently been her brother. They must have met only a moment before we ran across them, for the Ghost was just saying in a tone of unconcealed disappointment, ‘Oh…Reginald! It’s you, is it?’ ‘Yes, dear,’ said the Spirit. ‘I know you expected someone else. Can you…I hope you can be a little glad to see even me; for the present.’

‘I did think Michael would have come,’ said the Ghost . . . ‘Well. When am I going to be allowed to see him?’

‘There’s no question of being allowed, Pam. As soon as it’s possible for him to see you, of course he will. You need to be thickened up [the unredeemed are insubstantial, thus their description as “ghosts”] a bit.’

‘How?’ said the Ghost. The monosyllable was hard and a little threatening.

‘I’m afraid the first step is a hard one,’ said the Spirit. ‘But after that you’ll go on like a house on fire. You will become solid enough for Michael to perceive you when you learn to want Someone Else besides Michael. I don’t say “more than Michael,” not as a beginning. That will come later. It’s only the little germ of a desire for God that we need to start the process.’

‘Oh, you mean religion and all that sort of thing? This is hardly the moment . . . and from you, of all people. Well, never mind. I’ll do whatever’s necessary. What do you want me to do? Come on. The sooner I begin it, the sooner they’ll let me see my boy. I’m quite ready.’

‘But, Pam, do think! Don’t you see you are not beginning at all as long as you are in that state of mind? You’re treating God only as a means to Michael. But the whole thickening treatment consists in learning to want God for His own sake.’

‘You wouldn’t talk like that if you were a mother.’

‘You mean, if I were only a mother. But there is no such thing as being only a mother. You exist as Michael’s mother only because you first exist as God’s creature. That relation is older and closer. No, listen, Pam! He also loves. He also has suffered. He also has waited a long time.’

‘If He loved me He’d let me see my boy. If He loved me why did He take Michael away from me? I wasn’t going to say anything about that. But it’s pretty hard to forgive, you know.’

‘But He had to take Michael away. Partly for Michael’s sake…’

‘I’m sure I did my best to make Michael happy. I gave up my whole life . . .’

‘Human beings can’t make one another really happy for long. And secondly, for your sake. He wanted your merely instinctive love for your child (tigresses share that, you know!) to turn into something better. He wanted you to love Michael as He understands love. You cannot love a fellow-creature fully till you love God. Sometimes this conversion can be done while the instinctive love is still gratified. But there was, it seems, no chance of that in your case. The instinct was uncontrolled and fierce and monomaniac. Ask your daughter, or your husband. Ask our own mother. You haven’t once thought of her. . . .

‘This is all nonsense—cruel and wicked nonsense. What right have you to say things like that about Mother-love? It is the highest and holiest feeling in human nature.’ ‘Pam, Pam—no natural feelings are high or low, holy or unholy, in themselves. They are all holy when God’s hand is on the rein. They all go bad when they set up on their own and make themselves into false gods.’ ‘My love for Michael would never have gone bad. Not if we’d lived together for millions of years.’

‘You are mistaken. And you must know. Haven’t you met—down there—mothers who have their sons with them, in Hell? Does their love make them happy . . ?’

‘Give me my boy. Do you hear? I don’t care about all your rules and regulations. I don’t believe in a God who keeps mother and son apart. I believe in a God of love. No one had a right to come between me and my son. Not even God. Tell Him that to His face. I want my boy, and I mean to have him. He is mine, do you understand? Mine, mine, mine, for ever and ever.’

Exercising the right kind of family love is not always easy. Due to our sinful nature, it is often corrupted. Still, striving to build a healthy (and, dare I say, holy) family is quite an adventure. A final thought from C.S. Lewis.

Since the Fall no organization or way of life whatever has a natural tendency to go right. . . . The family, like the nation, can be offered to God, can be converted and redeemed, and will then become the channel of particular blessings and graces.

But, like everything else that is human, it needs redemption. Unredeemed, it will produce only particular temptations, corruptions, and miseries. Charity begins at home: so does un-charity.

By the conversion or sanctification of family life we must be careful to mean something more than the preservation of “love” in the sense of natural affection. Love (in that sense) is not enough. Affection, as distinct from charity, is not a cause of lasting happiness. Left to its natural bent affection affection becomes in the end greedy, naggingly solicitous, jealous, exacting, timorous. It suffers agony when its object is absent—but is not repaid by any long enjoyment when the object is present. . . . The greed to be loved is a fearful thing. . . .

Must we not abandon sentimental eulogies and begin to give practical advise on the high, hard, lovely, and adventurous art of really creating the Christian family? (“The Sermon and the Lunch”).