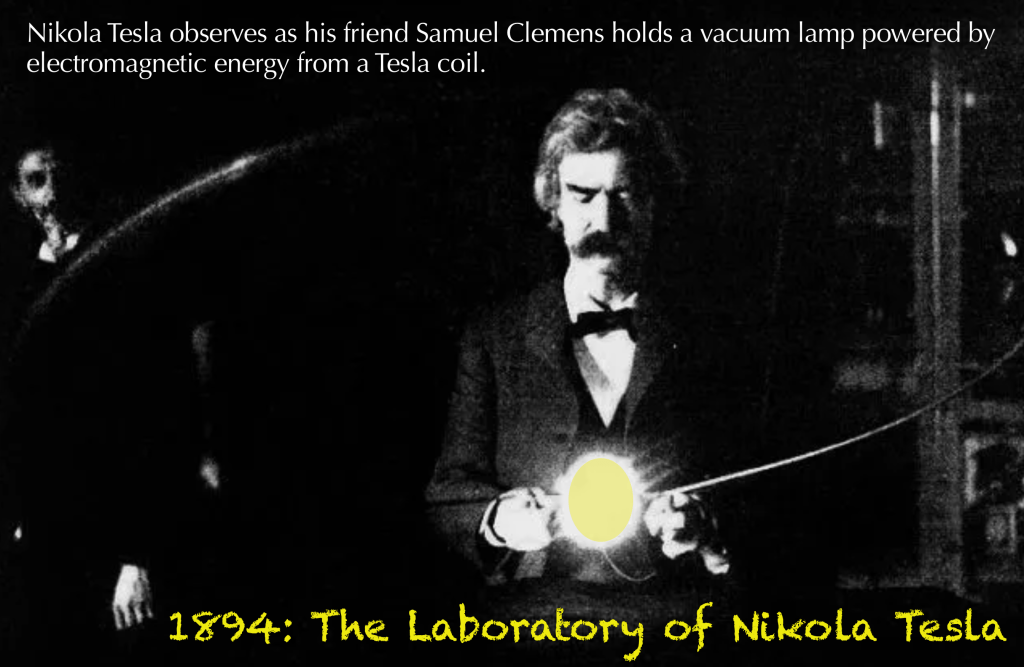

I recently uncovered a curious connection between C.S. Lewis and Tesla. (Not the current target of anarchist vandalism, the scientist.) While researching scientists living in the early twentieth century, a photograph of Tesla and his friend Mark Twain ignited my curiosity as to whether or not there might have been any connection between Lewis and Tesla.

C.S. Lewis (1898 – 1963) and Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943) never met or corresponded. And yet, they do possess a rather tenuous, speculative connection.

Their connection isn’t based on any similarities. Tesla was a radically innovative scientist. Lewis was a grounded literary master who was wisely suspicious of misplaced faith in scientism.

Despite the fact Tesla’s father and uncle were both Serbian Orthodox priests, and he maintained an interest in various religious traditions throughout his life, his adult beliefs were eclectic.

Lewis, the grandson of a Church of Ireland priest, went through a period of atheism before returning to Christianity as a devout member of the Anglican communion.

So, how might the two men have been connected? Before exploring the notion that they shared a mysterious source of inspiration, consider the application of a modern theory.

Six Degrees of Separation

Various experiments have supported the idea that people (in Western nations, at least) find it “truly possible to trace a social connection between any two random people within just six steps” (This is far more refined than the overlapping of lifespans as discussed here.)

But the pressing question remained: Why six? The answer has finally been revealed in a paper published in the journal Physical Review X. The study authors include researchers from Israel, Spain, Italy, Russia, Slovenia, and Chile.

For an academic study of the phenomenon check out “Why Are There Six Degrees of Separation in a Social Network?”

Even without the existence of social media, which some have argued may reduce “6 Degrees of Separation [to] 2,” I uncovered a pair of paths connecting Tesla and Lewis.

The first example is the more “direct,” but the second includes as an intermediate link, a writer of great importance to C.S. Lewis.

Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943)

Had as a friend who visited his laboratory, and later invited the inventor to attend his daughter’s wedding…

Mark Twain (1835 – 1910)

Who, after offering a scathing indictment of British colonialism, officially introduced to deliver a 1900 speech in New York…

Winston Churchill (1874 – 1965)

Who offered “the honour of becoming a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE)” to…

C.S. Lewis (1898 – 1963)

one of the most renowned scholars to ever teach at Oxford and Cambridge.

And an alternate path:

Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943)

Had as a friend who visited his laboratory, and later invited the inventor to attend his daughter’s wedding…

Mark Twain (1835 – 1910)

Who maintained a longtime literary and personal friendship with…

George MacDonald (1824 – 1905)

Who received as a gift A Speech and Two Poems with a personal letter from Irish poet…

William Butler Yeats (1865 – 1939)

Who, on more than one occasion, entertained in his home…

C.S. Lewis (1898 – 1963)

who, coincidentally, regarded the very same George MacDonald as one of his greatest mentors.

Tracking down these relationship paths was not that difficult. It was actually fun. If I wasn’t so busy, I would create a few more examples.

Was there Another Connection?

Nikola Tesla (Никола Тесла) was a Serbian-American inventor and futurist. His design of the alternating current (AC) electricity system was a breakthrough. As noted above, he was not a credal Christian. In “A Machine to End War,” he described his beliefs in the following manner.

To me, the universe is simply a great machine which never came into being and never will end. The human being is no exception . . . Man, like the universe, is a machine. . . . what we call “soul “ or “spirit,” is nothing more than the sum of the functionings of the body. When this functioning ceases, the “soul” or the “spirit” ceases likewise.

The possible connection between Tesla and the Inklings, postulated by a sensationalist Anglican priest, is offered in Secrets of Rennes Le Chateau. The author, R. Lionel Fanthorpe, an Anglican priest who believes “there are as many roads to the loving God of all mankind as there are individual human beings,” has written about many offbeat subjects.

In the aforementioned work, he references passages from J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams and George MacDonald as writers whose fiction may “contain hints about the Rennes-le-Château enigma.” He immediately follows this discussion with the case of “another contemporary of theirs [who] was one of the strangest and most brilliant men” of his age, Nikola Tesla.

He ends the chapter with the question, “what if the enigma with which all our Men of Mystery seem to have been involved was some form of superior communication? But communication with what? Or with whom?”

I doubt there is any connection in the source of the inspiration experienced by the Inklings, Tesla and the church at Rennes-le-Château. That said, it is an odd place of worship, due to the renovations made by its eccentric Roman Catholic priest, François-Bérenger Saunière (1852 – 1917).

Among the alterations made was the addition of a holy water font resting on the back of a devil or demon. That certainly qualifies as a “mysterious” decision. A mystery with which the Inklings bear no connection.

Ultimately, Fanthorpe’s odd musings are illusory. Better to dismiss them and focus on the actual connection between C.S. Lewis and Nikola Tesla – one documented through the Six Degrees of Separation model.