C.S. Lewis possessed a gift for languages. Although he was not a philologist like his friend J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis was well educated and read and spoke a variety of languages.

In fact, when he and his wife played Scrabble, they allowed for the use of words from any language! For the record, though, he does confess to a German professor that his grasp of that tongue is “wretched.”

The only bona fide genius I’ve known was a classmate at the University of Washington. While I was struggling with classical Greek, in preparation for seminary, at the age of 23 Bruce already possessed four master’s degrees and was closing in on his PhD in Linguistics. He spoke fifteen languages, but could read nineteen.

Of course, that is still a small portion of the 7,168 languages Ethnologue tells us are in use today.

This enormous number – which doesn’t include unknown languages spoken among untouched people groups – accounts for the fact that thousands of Christians are laboring now in groups such as Lutheran Bible Translators to make the Scriptures available to all people.

Sometimes this involves creating a written language itself, where only an oral version exists. The largest such organization, Wycliffe Global Alliance, reports that “Bible translation is currently happening in 2,846 languages in 157 countries.”

While the Bible’s translation is certainly of utmost importance, it is wonderful to know that other valuable literature is also made available to readers who could not decipher the language in which it was originally composed.

Lewis, in fact, was a translator in his own right. Beyond the literal translation of works from one tongue to another, Lewis also functioned as a “translator” of complex concepts and eternal truths. I once described this as C.S. Lewis’ bilingualism.

How many extremely intelligent and well educated people do you know . . . who can actually communicate with those of us possessing normal human intelligence? That talent is a rarity.

And it is precisely what makes C.S. Lewis such an unusual man. He was brilliant. Yet he could communicate with the common person – even the child – just as easily as he conversed with his fellow university dons.

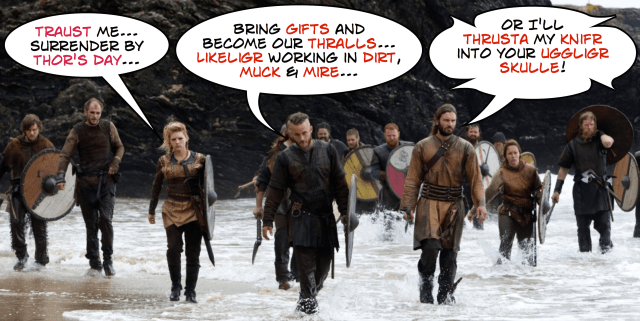

C.S. Lewis mastered a number of modern languages, but it was his study of historic languages that especially inspired him. Icelandic, with its similarity to Old Norse, is one example about which I have written.

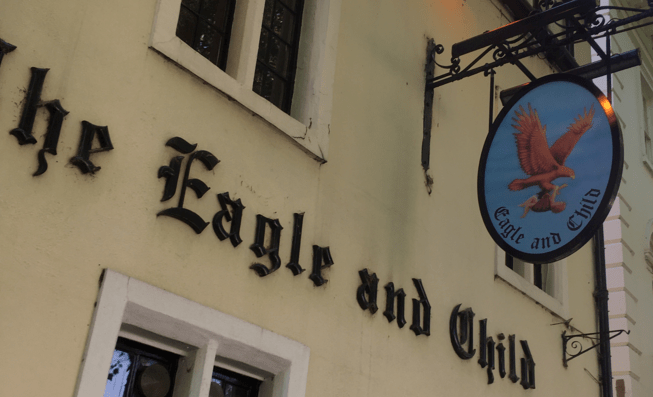

. . . J.R.R. Tolkien and his friend C.S. Lewis established a group called Kolbitár which was devoted to reading Icelandic and Norse sagas. The word itself means “coal biter” and refers to those in a harsh environment drawing so close to the fire’s warmth they can almost bite the coals.

Another example is Old English. Along with Middle English, birthed by the Norman Conquest, these were essential elements of his training as one of the preeminent English scholars of Oxford and Cambridge. And these languages were not merely dusty relics. I encourage the curious to read “C.S. Lewis’s Unpublished Letter in Old English,” which appeared in the journal VII.

In 1926 C.S. Lewis wrote his friend Nevill Coghill a letter in Old English, a language also known as Anglo-Saxon. Unreadable for most current readers of Lewis, it understandably does not appear in his three-volume Collected Letters.

In the essay, George Musacchio provides an illuminating outline of Lewis’ diverse expertise with languages, both “foreign and domestic.” Lewis began the letter to his friend with the following salutation.

“Leowis ceorl hateð gretan Coghill eoorl luflice ond freondlice.”

Which translates as: “Lewis the churl bids to greet Coghill the earl.”

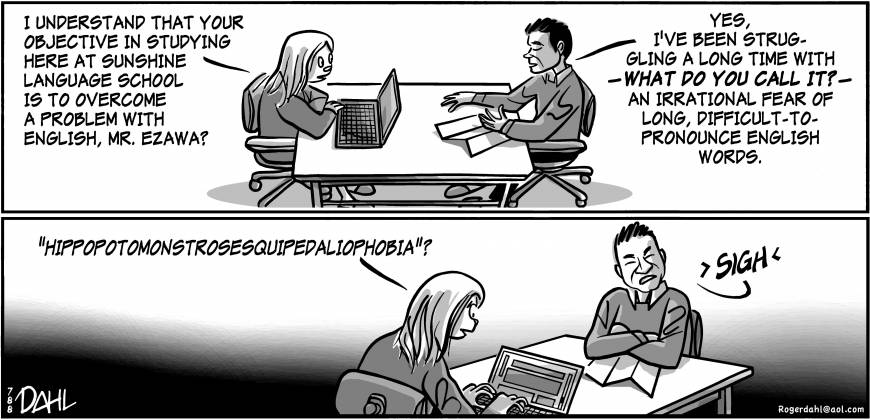

Is English Really that Difficult to Learn?

English is reputed to be one of the most challenging languages to learn. (More on this in a moment.) For example, the simple sentence which follows consists of a mere seven words, but holds seven different meanings, dependent upon which word is emphasized.

“I never said she stole my money.”

This example comes from an article entitled “English is Hard, But Can Be Understood Through Tough Thorough Thought Though.”

Rosetta Stone answers the question of how hard it is to learn English by saying “it depends on your first language.”

In addition to the fact that “spelling is a poor indicator of pronunciation,” English possesses numerous “specific rules,” and complements this burden with the fact that “some rules have lots of exceptions.” The complexity is due to the language’s history, which also gave rise to its mammoth vocabulary.

English has a lot of words—Webster’s English Dictionary includes approximately 470,000 entries, and it’s estimated that the broader English vocabulary may include around a million words. . . .

English has such a broad vocabulary because it’s a blend of several different root languages. While English is a West Germanic language in its sounds and grammar, much of the vocabulary also stems from Romance languages, such as Latin, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese.

One result of combining these various root languages is that the English vocabulary includes a ton of synonyms . . . And unfortunately, most of these synonyms aren’t fully interchangeable, so the exact word you choose does have an impact on the overall meaning.

It turns out English doesn’t even rank in the top three most difficult languages for the speakers of the five largest language groups. The ranked listings do include, however, Arabic, Japanese, Russian, and Mandarin.

So, let’s reverse the question for a moment. Which languages are the most difficult for a native English speaker to learn? Unbabel lists ten. Fortunately, only one of them is on my wish list.

Babbel Magazine has an article approaching that question from the opposite end. Which language is easiest for English speakers to learn.

This may come as a surprise, but we have ranked Norwegian as the easiest language to learn for English speakers. Norwegian is a member of the Germanic family of languages — just like English! This means the languages share quite a bit of vocabulary, such as the seasons vinter and sommer (we’ll let you figure out those translations).

Another selling point for Norwegian: the grammar is pretty straightforward, with only one form of each verb per tense. And the word order closely mimics English. For example, “Can you help me?” translates to Kan du hjelpe meg? — the words are in the same order in both languages, so mastering sentence structure is a breeze!

Finally, you’ll have a lot more leeway with pronunciation when learning Norwegian. That’s because there are a vast array of different accents in Norway and, therefore, more than one “correct way” to pronounce words.

An article I wrote seven years ago hints at that same conclusion. I made this informative, and mildly threatening, illustration for “Norse Linguistic Invasion.”

Oxford Royale Academy lists several reasons why English is especially challenging to new students. The following issue of “irregularities” also plagues countless native speakers.

One of the hardest things about English is that although there are rules, there are lots of exceptions to those rules – so just when you think you’ve got to [come to] grips with a rule, something comes along to shatter what you thought you knew by contradicting it.

A good example is the rule for remembering whether a word is spelt “ie” or “ei:” “I before E except after C.” Thus “believe” and “receipt.”

But this is English – it’s not as simple as that. What about “science?” Or “weird?” Or “seize?”

There are loads of irregular verbs, too, such as “fought”, which is the past tense of “fight”, while the past tense of “light” is “lit.” So learning English isn’t just a question of learning the rules – it’s about learning the many exceptions to the rules.

The numerous exceptions make it difficult to apply existing knowledge and use the same principle with a new word, so it’s harder to make quick progress.

And even some of the normative “rules” are difficult to grasp. One example is that there’s a very specific order that adjectives must be listed ahead of a noun. According to Rosetta Stone,

The adjective order is: quantity, opinion, size, age, shape, color, origin/material, qualifier, and then noun. For example, “I love my big old yellow dog.” Saying these adjectives in any other order, like “I love my yellow old big dog,” will sound wrong, even when otherwise the sentences are exactly the same and communicate the same thing. Keeping rules like this in mind can be tricky, and it takes a lot of practice to get it right.

Adjective order is seldom considered, in part because it’s not considered good writing to string too many such words together. But apparently there are right and wrong ways to organize any such list.

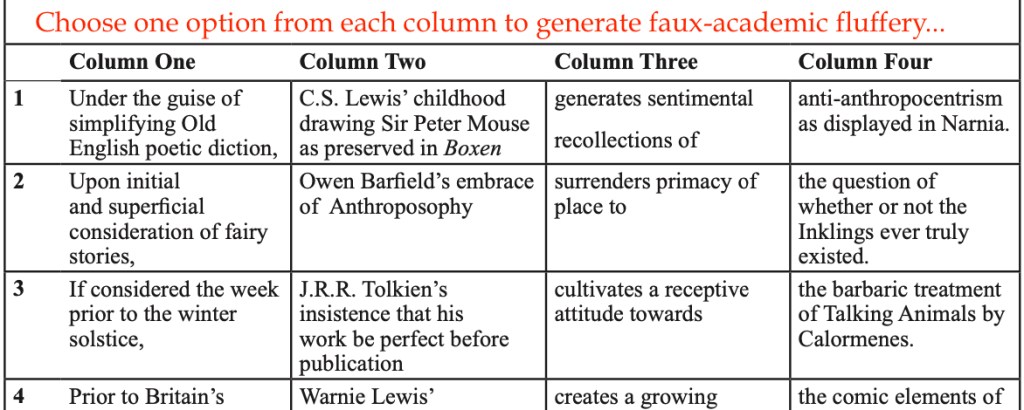

Royal Order of Adjectives

Most students aren’t taught about adjective order in school and instead learn it through listening and reading. In English, the rules regarding adjective order are more specific than they are in other languages; that is why saying adjectives in a specific order sounds “right,” and deviating from that order makes a statement sound “wrong,” even if it’s otherwise grammatically perfect.

And, since we’re talking about English, even this Royal Order of Adjectives rule has exceptions!

The hierarchy is not absolute, and there is some wiggle room among the “fact” categories – size, age, and so on – in the middle.

Native speakers are often delighted when they learn about this law and discover how flawlessly they apply it. It even went viral in 2016 . . . The tweet attached a paragraph by etymologist Mark Forsyth . . . giving an example that uses all the categories according to the OSASCOMP hierarchy: “a lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife.”

I do not ever recall being taught (or reading on my own) about the “Royal Order of Adjectives.” Nevertheless, I don’t feel too embarrassed at acknowledging my previous ignorance, since even Lewis himself was comfortable in expressing gratitude for being introduced to new words. For example, when he thanked Dorothy Sayers for enlarging his vocabulary with her work on Dante.

So, is English all that challenging? Well, C.S. Lewis did his part to make it less daunting, joining a public debate in Britain, with an unexpected argument. Discussing English’s previously noted problem with inconsistencies and confusion in spelling, the don offered a simple solution.

In a column on Lewis and the history of words, I included an extended passage from a letter Lewis wrote challenging a contemporary British effort to “reform” spelling. Surprisingly, he argued against the necessity for uniformity in spelling. After explaining why our language functions as it does, he advocates:

As things are, surely Liberty is the simple and inexpensive ‘Reform’ we need? This would save children and teachers thousands of hours’ work.

Surely all but the most diehard grammarians would be sympathetic to his argument.

Next week I plan to write about another linguistic matter closely associated with the Inklings – the creation of new words and languages.