What’s with pastors? As one, I probably know more than the typical person does about them – and all too often, they disappoint.

That’s a bit harsh. Most pastors are pretty selfless. That’s fairly evident in their salaries (if they even receive one). And, trust me, trying to be a faithful leader and peacemaker in any group comprised of human beings, is no easy task.

My sainted grandmother, born at the end of the nineteenth century, was the daughter of Norwegian immigrants. She was an authentic follower of Jesus, and when she was young the sermons at Fordefjord Lutheran Church* were preached in the immigrants’ tongue. We occasionally talked about how scandalized she was when one of the ministers serving the congregation pronounced “helvete vil være fullt av pastorer” (hell will be full of pastors).

Well, not “full” perhaps, but in principle he was right. And, sadly, his warning is not at all shocking to us today. We read regularly about clergy who are arrested for violating the trust of the most vulnerable. Likewise, we hear about the outrageous wealth of some ministers (including, it seems, nearly every televangelist). Even pastors in small enclaves with little access to the temptation offered by easily accessible cash, can too often succumb to the sirens of pride and power, twisting their pastoral authority into a weapon to abuse others. (It’s the opposite of the messianic promise found in Isaiah 2:4.)

It’s almost enough to drive a person from the Lord’s house. But that is not the answer, of course. Finding a truly Christian church, with a pastor earnestly (albeit imperfectly) pursuing his holy vocation, is the best course.

The Scriptures say many things about ministry, and Jesus himself provides the perfect example of willingness to lay down one’s life for the sheep.

The letter of James cautions those considering a life of “ministry” that they will face a stricter judgment than the laity (which comes from λαός which refers to the people at large).

Personally, I especially appreciate being reminded of God’s warning to religious leaders from the lips of Jeremiah. (I also appreciate the ironic tone of God’s judgment.)

“Woe to the shepherds who destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture!” declares the Lord. Therefore thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, concerning the shepherds who care for my people: “You have scattered my flock and have driven them away, and you have not attended to them. Behold, I will attend to you for your evil deeds,” declares the Lord.

The picture at the top of this column comes from one of Mark Twain’s travelogues. It illustrates the vindictive priest Fulbert, in Twain’s retelling of the story of Abelard and Héloïse, 12th century lovers. More about that momentarily. Abelard was a prominent philosopher who tangled for several years with Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, a significant dispute ably discussed here.

Abelard and the Inklings

Abelard (c. 1079-1142) was a philosopher who, as was common during the Middle Ages, was also a theologian. Among his contributions to religion was revising the Roman Catholic doctrine of limbus infantium (Limbo for unbaptized infants).

In popular culture, Abelard’s love affair with his eventual “wife” is more prominent than his religious pursuits. Although Abelard was a famous figure during the medieval period, he did not feature significantly in C.S. Lewis’ thought. He did, however, exert a prominent influence on Charles Williams’ Place of the Lion, a volume Lewis praised.

In “Friendship in The Place of the Lion,” Dan Hamilton provides a very accessible synopsis of Williams’ book. He describes the experience of a primary character, who is writing her dissertation on “Pythagorean Influences on Abelard.” As she struggles with the appearance of supernatural phenomena, “she encounters the specter of Abelard, a major subject of her studies. But he is dead, and powerless to give her any aid, not even a meaningful word.” The “archetypes” in the story, by contrast, possess genuine power. It is a very unique book.

Returning to Mark Twain’s retelling of the popular medieval tale, we leave the realm of platonic philosophy, and enter the world of sordid human activities. Twain, you see, was not sympathetic to Abelard’s wooing of a young student and his eventual repentance. In his account, Twain desired “to show the public that they have been wasting a good deal of marketable sentiment very unnecessarily.” If you are curious as to his perspective on the events, continue reading.

Twain’s Take on Abelard and Héloïse

(not brief, but well worth reading)

In his own words, Twain’s “faithful” version of their story – but first, he begins with a description of their shared gravesite.

But among the thousands and thousands of tombs in Père la Chaise [cemetery] there is one that no man, no woman, no youth of either sex, ever passes by without stopping to examine. Every visitor has a sort of indistinct idea of the history of its dead, and comprehends that homage is due there, but not one in twenty thousand clearly remembers the story of that tomb and its romantic occupants. This is the grave of Abelard and Heloise – a grave which has been more revered, more widely known, more written and sung about and wept over, for seven hundred years, than any other in Christendom, save only that of the Saviour.

All visitors linger pensively about it; all young people capture and carry away keepsakes and mementoes of it; all Parisian youths and maidens who are disappointed in love come there to bail out when they are full of tears; yea, many stricken lovers make pilgrimages to this shrine from distant provinces to weep and wail and “grit” their teeth over their heavy sorrows, and to purchase the sympathies of the chastened spirits of that tomb with offerings of immortelles and budding flowers.

Go when you will, you find somebody snuffling over that tomb. Go when you will, you find it furnished with those bouquets and immortelles. Go when you will, you find a gravel-train from Marseilles arriving to supply the deficiencies caused by memento-cabbaging vandals whose affections have miscarried.

Yet who really knows the story of Abelard and Heloise? Precious few people. The names are perfectly familiar to every body, and that is about all. With infinite pains I have acquired a knowledge of that history, and I propose to narrate it here, [italics added] partly for the honest information of the public and partly to show that public that they have been wasting a good deal of marketable sentiment very unnecessarily.

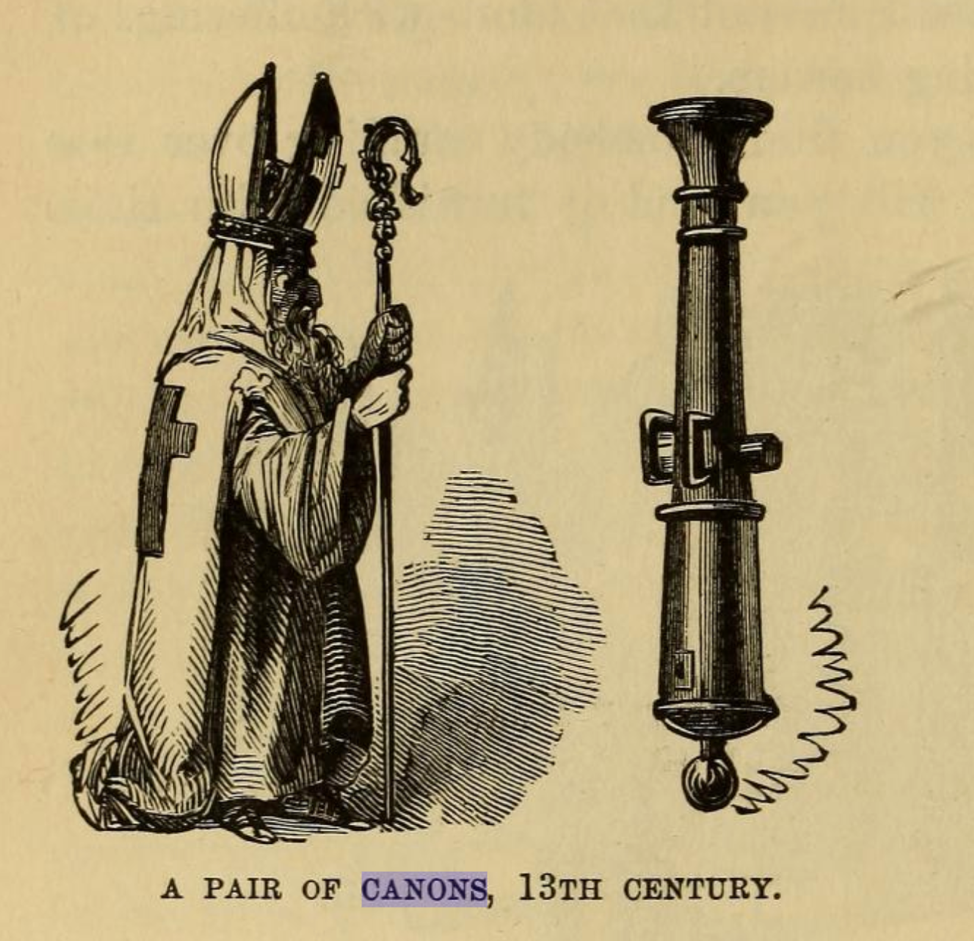

Heloise was born seven hundred and sixty-six years ago. She may have had parents. There is no telling. She lived with her uncle Fulbert, a canon of the cathedral of Paris. I do not know what a canon of a cathedral is, but that is what he was. He was nothing more than a sort of a mountain howitzer, likely, because they had no heavy artillery in those days. Suffice it, then, that Heloise lived with her uncle the howitzer, and was happy.

She spent the most of her childhood in the convent of Argenteuil – never heard of Argenteuil before, but suppose there was really such a place. She then returned to her uncle, the old gun, or son of a gun, as the case may be, and he taught her to write and speak Latin, which was the language of literature and polite society at that period.

Just at this time, Pierre Abelard, who had already made himself widely famous as a rhetorician, came to found a school of rhetoric in Paris. The originality of his principles, his eloquence, and his great physical strength and beauty created a profound sensation. He saw Heloise, and was captivated by her blooming youth, her beauty and her charming disposition. He wrote to her; she answered. He wrote again, she answered again. He was now in love. He longed to know her – to speak to her face to face.

His school was near Fulbert’s house. He asked Fulbert to allow him to call. The good old swivel saw here a rare opportunity: his niece, whom he so much loved, would absorb knowledge from this man, and it would not cost him a cent. Such was Fulbert – penurious . . . He asked Abelard to teach her.

Abelard was glad enough of the opportunity. He came often and staid long. A letter of his shows in its very first sentence that he came under that friendly roof like a cold-hearted villain as he was, with the deliberate intention of debauching a confiding, innocent girl. This is the letter :

“I can not cease to be astonished at the simplicity of Fulbert; I was as much surprised as if he had placed a lamb in the power of a hungry wolf. Heloise and I, under pretext of study, gave ourselves up wholly to love, and the solitude that love seeks our studies procured for us. Books were open before us, but we spoke oftener of love than philosophy, and kisses came more readily from our lips than words.”

And so, exulting over an honorable confidence which to his degraded instinct was a ludicrous “simplicity,” this unmanly Abelard seduced the niece of the man whose guest he was. Paris found it out. Fulbert was told of it – told often – but refused to believe it. He could not comprehend how a man could be so depraved as to use the sacred protection and security of hospitality as a means for the commission of such a crime as that. But when he heard the rowdies in the streets singing the love-songs of Abelard to Heloise, the case was too plain – love-songs come not properly within the teachings of rhetoric and philosophy.

He drove Abelard from his house. Abelard returned secretly and carried Heloise away to Palais, in Brittany, his native country. Here, shortly afterward, she bore a son, who, from his rare beauty, was surnamed Astrolabe. . . . The girl’s flight enraged Fulbert, and he longed for vengeance, but feared to strike lest retaliation visit Heloise – for he still loved her tenderly. At length Abelard offered to marry Heloise – but on a shameful condition: that the marriage should be kept secret from the world, to the end that (while her good name remained a wreck, as before) his priestly reputation might be kept untarnished. It was like that miscreant.

Fulbert saw his opportunity and consented. He would see the parties married, and then violate the confidence of the man who had taught him that trick; he would divulge the secret and so remove somewhat of the obloquy that attached to his niece’s fame. But the niece suspected his scheme. She refused the marriage, at first; she said Fulbert would betray the secret to save her, and besides, she did not wish to drag down a lover who was so gifted, so honored by the world, and who had such a splendid career before him. It was noble, self-sacrificing love, and characteristic of the pure-souled Heloise, but it was not good sense.

But she was overruled, and the private marriage took place. Now for Fulbert! The heart so wounded should be healed at last; the proud spirit so tortured should find rest again; the humbled head should be lifted up once more. He proclaimed the marriage in the high places of the city, and rejoiced that dishonor had departed from his house. But lo! Abelard denied the marriage! Heloise denied it! The people, knowing the former circumstances, might have believed Fulbert, had only Abelard denied it, but when the person chiefly interested – the girl herself – denied it, they laughed despairing Fulbert to scorn.

The poor canon of the cathedral of Paris was spiked again. The last hope of repairing the wrong that had been done his house was gone. What next? Human nature suggested revenge. He compassed it. The historian says: “Ruffians, hired by Fulbert, fell upon Abelard by night, and inflicted upon him a terrible and nameless mutilation.”

I am seeking the last resting-place of those “ruffians.” When I find it I shall shed some tears on it, and stack up some bouquets and immortelles, and cart away from it some gravel whereby to remember that howsoever blotted by crime their lives may have been, these ruffians did one just deed, at any rate, albeit it was not warranted by the strict letter of the law.

Heloise entered a convent and gave good-bye to the world and its pleasures for all time. For twelve years she never heard of Abelard – never even heard his name mentioned. She had become prioress of Argenteuil, and led a life of complete seclusion. She happened one day to see a letter written by him, in which he narrated his own history. She cried over it, and wrote him. He answered, addressing her as his “sister in Christ.”

They continued to correspond, she in the un-weighed language of unwavering affection, he in the chilly phraseology of the polished rhetorician. She poured out her heart in passionate, disjointed sentences; he replied with finished essays, divided deliberately into heads and sub-heads, premises and argument. She showered upon him the tenderest epithets that love could devise, he addressed her from the North Pole of his frozen heart as the “Spouse of Christ!” The abandoned villain!

On account of her too easy government of her nuns, some disreputable irregularities were discovered among them, and the Abbot of St. Denis broke up her establishment. Abelard was the official head of the monastery of St. Grildas de Ruys, at that time, and when he heard of her homeless condition a sentiment of pity was aroused in his breast (it is a wonder the unfamiliar emotion did not blow his head off), and he placed her and her troop in the little oratory of the Paraclete, a religious establishment which he had founded.

She had many privations and sufferings to undergo at first, but her worth and her gentle disposition won influential friends for her, and she built up a wealthy and flourishing nunnery. She became a great favorite with the heads of the church, and also the people, though she seldom appeared in public. She rapidly advanced in esteem, in good report and in usefulness, and Abelard as rapidly lost ground. The Pope so honored her that he made her the head of her order.

Abelard, a man of splendid talents, and ranking as the first debater of his time, became timid, irresolute, and distrustful of his powers. He only needed a great misfortune to topple him from the high position he held in the world of intellectual excellence, and it came. Urged by kings and princes to meet the subtle St. Bernard in debate and crush him, he stood up in the presence of a royal and illustrious assemblage, and when his antagonist had finished he looked about him, and stammered a commencement; but his courage failed him, the cunning of his tongue was gone: with his speech unspoken, he trembled and gat down, a disgraced and vanquished champion.

He died a nobody, and was buried at Cluny, A.D., 1144. They removed his body to the Paraclete afterward, and when Heloise died, twenty years later, they buried her with him, in accordance with her last wish. He died at the ripe age of 64, and she at 63. After the bodies had remained entombed three hundred years, they were removed once more. They were removed again in 1800, and finally, seventeen years afterward, they were taken up and transferred to Pere la Chaise, where they will remain in peace and quiet until it comes time for them to get up and move again.

History is silent concerning the last acts of the mountain howitzer. Let the world say what it will about him, I, at least, shall always respect the memory and sorrow for the abused trust, and the broken heart, and the troubled spirit of the old smooth-bore. Rest and repose be his!

Such is the story of Abelard and Heloise. (Innocents Abroad).

* Later Fordefjord was unimaginatively renamed “First Lutheran Church.”

A novel entitled Peter Abelard was published in 1933 by Helen Waddell. It is available at Internet Archive for those who prefer their history via the medium of historical fiction. The illustration below, apparently imitating a fading fresco, comes from that volume.