Should literary critics look down on authors whose work proves popular with “common” people? Is it appropriate for the literary elite to smirk dismissively whenever the prose of a writer outside their circle resonates with the masses?

Should literary critics look down on authors whose work proves popular with “common” people? Is it appropriate for the literary elite to smirk dismissively whenever the prose of a writer outside their circle resonates with the masses?

These, my friends, are rhetorical questions. The answer to both is “no,” and if you believe otherwise, you probably won’t find yourself too comfortable with the opinions shared here at Mere Inkling.

I believe each piece of literature, regardless of its source, should be judged on its own merits. Not all genres appeal to all people. And not all writers compose their works with equal skill. Nevertheless, it is possible for even a poor miner to strike gold.

Likewise, an accomplished writer is not infallible. Even a master wildcatter can sink a dry well.

I’ve been writing an article about Civil War chaplain who became one of America’s most popular writers during the nineteenth century. In fact, many years his novels outsold the works of Samuel Clemens himself.

And yet, despite his success—or possibly, because average people enjoyed his stories—he received an extraordinary amount of criticism from the literary establishment.

I’m going to share his insights about writing in a moment, but before doing so, I want to draw a parallel with one of the twentieth century’s most gifts authors. C.S. Lewis was loved by common women and men of Britain and other English-speaking countries. And yet, this very popularity undermined his standing in the world of academia and, I daresay, literary snobbery.

Lewis describes this condescending mindset in a 1939 essay entitled, “High Brows and Low Brows.”

The great authors of the past wrote to entertain the leisure of their adult contemporaries, and a man who cared for literature needed no spur and expected no good conduct marks for sitting down to the food provided for him.

Boys at school were taught to read Latin and Greek poetry by the birch, and discovered the English poets as accidentally and naturally as they now discover the local cinema. Most of my own generation, and many, I hope, of yours, tumbled into literature in that fashion.

Of each of us some great poet made a rape when we still wore Eton collars. Shall we be thought immodest if we claim that most of the books we loved from the first were good books and our earliest loves are still unrepented? If so, that very fact bears witness to the novelty of the modern situation; to us, the claim that we have always liked Keats is no prouder than the claim that we have always liked bacon and eggs. For there are changes afoot.

I foresee the growth of a new race of readers and critics to whom, from the very outset, good literature will be an accomplishment rather than a delight, and who will always feel, beneath the acquired taste, the backward tug of something else which they feel merit in resisting.

Such people will not be content to say that some books are bad or not very good; they will make a special class of “lowbrow” art which is to be vilified, mocked, quarantined, and sometimes (when they are sick or tired) enjoyed. They will be sure that what is popular must always be bad, thus assuming that human taste is naturally wrong, that it needs not only improvement and development but veritable conversion.

For them a good critic will be, as the theologians say, essentially a “twice-born” critic, one who is regenerate and washed from his Original Taste. They will have no conception, because they have had no experience, of spontaneous delight in excellence.

I confess I’ve sometimes felt slightly embarrassed when in the presence of a group of people singing the praises of authors of fiction popular among the well-educated. Sometimes I don’t even recognize their names, much less have an idea of what they have written.

Part of my “handicap” rises from the fact that I’m by and large a non-fiction sort of guy. As seminary I was less enraptured by abstract “systematic theology” than the time-proven lessons learned during the Church’s two millennia history. Likewise, I found “practical theology” far more beneficial. After all, I was being equipped not to be a theologian per se, but to become a shepherd entrusted with the cura animarum (the cure of souls).

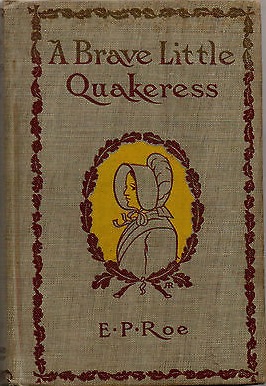

In that spirit, valuing history and lessons I could put into practice as a pastor and writer, I have been researching the legacy of Edward Payson Roe (1838-1888). He was a Presbyterian pastor who served as a chaplain in the Union cavalry, and later as a military hospital chaplain.

After the war, Roe served a congregation, and eventually turned his energies to writing wholesome fiction. He played a key role in helping many suspicious Protestants realize that, like manna, fiction was neither good nor bad. It’s effects depended on the use to which it was put. Roe proved quite popular with readers. Less so with the literary establishment.

The following account comes from an essay about his life solicited by one of the prominent magazines of his day. It is well worth reading, touching as it does on a broad range of subjects, including international copyrights and the vagaries of publishing in the late 1800s. Most precious, though, are the echoes of Roe’s humility and his realistic understanding of the vocation of writing.

“While writing my first story, I rarely thought of the public, the characters and their experiences absorbing me wholly. When my narrative was actually in print, there was wakened a very deep interest as to its reception. I had none of the confidence resulting from the gradual testing of one’s power or from association with literary people, and I also was aware that, when published, a book was far away from the still waters of which one’s friends are the protecting headlands.

“That I knew my work to be exceedingly faulty goes without saying; that it was utterly bad, I was scarcely ready to believe. Dr. Field, noted for his pure English diction and taste, would not publish an irredeemable story, and the constituency of the New York ‘Evangelist’ is well known to be one of the most intelligent in the country.

“Friendly opinions from serial readers were reassuring as far as they went, but of course the great majority of those who followed the story were silent. A writer cannot, like a speaker, look into the eyes of his audience and observe its mental attitude toward his thought. If my memory serves me, Mr. R.R. Bowker was the earliest critic to write some friendly words in the ‘Evening Mail;’ but at first my venture was very generally ignored.

Then some unknown friend marked an influential journal published in the interior of the State and mailed it so timely that it reached me on Christmas eve. I doubt if a book was ever more unsparingly condemned than mine in that review, whose final words were, ‘The story is absolutely nauseating.’ In this instance and in my salad days I took pains to find out who the writer was, for if his view was correct I certainly should not engage in further efforts to make the public ill.

“I discovered the reviewer to be a gentleman for whom I have ever had the highest respect as an editor, legislator, and honest thinker. My story made upon him just the impression he expressed, and it would be very stupid on my part to blink the fact. Meantime, the book was rapidly making for itself friends and passing into frequent new editions. Even the editor who condemned the work would not assert that those who bought it were an aggregation of asses. People cannot be found by thousands who will pay a dollar and seventy-five cents for a dime novel or a religious tract.

“I wished to learn the actual truth more sincerely than any critic to write it, and at last I ventured to take a copy to Mr. George Ripley, of the New York ‘Tribune.’ ‘Here is a man,’ I thought, ‘whose fame and position as a critic are recognized by all. If he deigns to notice the book, he will not only say what he thinks, but I shall have much reason to think as he does.’ Mr. Ripley met the diffident author kindly, asked a few questions, and took the volume. A few weeks later, to my great surprise, he gave over a column to a review of the story. Although not blind to its many faults, he wrote words far more friendly and inspiring than I ever hoped to see; it would seem that the public had sanctioned his verdict

“From that day to this these two instances have been types of my experience with many critics, one condemning, another commending. There is ever a third class who prove their superiority by sneering at or ignoring what is closely related to the people. Much thought over my experience led to a conclusion which the passing years confirm: the only thing for a writer is to be himself and take the consequences. Even those who regard me as a literary offender of the blackest dye have never named imitation among my sins.

“As successive books appeared, I began to recognize more and more clearly another phase of an author’s experience. A writer gradually forms a constituency, certain qualities in his book appealing to certain classes of minds. In my own case, I do not mean classes of people looked at from the social point of view. A writer who takes any hold on popular attention inevitably learns the character of his constituency. He appeals, and minds and temperaments in sympathy respond. Those he cannot touch go on their way indifferently; those he offends may often strike back. This is the natural result of any strong assertion of individuality.

“Certainly, if I had my choice, I would rather write a book interesting to the young and to the common people, whom Lincoln said ‘God must love, since He made so many of them.’ The former are open to influence; the latter can be quickened and prepared for something better. As a matter of fact, I find that there are those in all classes whom my books attract, others who are repelled, as I have said.

“It is perhaps one of the pleasantest experiences of an author’s life to learn from letters and in other ways that he is forming a circle of friends, none the less friendly because personally unknown. Their loyalty is both a safeguard and an inspiration. On one hand, the writer shrinks from abusing such regard by careless work; on the other, he is stimulated and encouraged by the feeling that there is a group in waiting who will appreciate his best endeavor.

“While I clearly recognize my limitations, and have no wish to emulate the frog in the fable, I can truthfully say that I take increasing pains with each story, aiming to verify every point by experience—my own or that of others. Not long since, a critic asserted that changes in one of my characters, resulting from total loss of memory, were preposterously impossible. If the critic had consulted Ribot’s ‘Diseases of Memory,’ or some experienced physician, he might have written more justly.

“I do not feel myself competent to form a valuable opinion as to good art in writing, and I cannot help observing that the art doctors disagree woefully among themselves. Truth to nature and the realities, and not the following of any school or fashion, has ever seemed the safest guide. I sometimes venture to think I know a little about human nature. My active life brought me in close contact with all kinds of people; there was no man in my regiment who hesitated to come to my tent or to talk confidentially by the campfire, while scores of dying men laid bare to me their hearts. I at least know the nature that exists in the human breast.

“It may be inartistic, or my use of it all wrong. That is a question which time will decide, and I shall accept the verdict. Over twelve years ago, certain oracles, with the voice of fate, predicted my speedy eclipse and disappearance. Are they right in their adverse judgment? I can truthfully say that now, as at the first, I wish to know the facts in the case. The moment an author is conceited about his work, he becomes absurd and is passing into a hopeless condition. If worthy to write at all, he knows that he falls far short of his ideals; if honest, he wishes to be estimated at his true worth, and to cast behind him the mean little Satan of vanity. If he walks under a conscious sense of greatness, he is a ridiculous figure, for beholders remember the literary giants of other days and of his own time, and smile at the airs of the comparatively little man. On the other hand, no self-respecting writer should ape the false deprecating ‘’umbleness’ of Uriah Heep. In short, he wishes to pass, like a coin, for just what he is worth.

“Mr. Matthew Arnold was ludicrously unjust to the West when he wrote, ‘The Western States are at this moment being nourished and formed, we hear, on the novels of a native author called Roe.’ Why could not Mr. Arnold have taken a few moments to look into the bookstores of the great cities of the West, in order to observe for himself how the demand of one of the largest and most intelligent reading publics in the world is supplied? He would have found that the works of Scott and Dickens were more liberally purchased and generally read than in his own land of ‘distinction.’ He should have discovered when in this country that American statesmen (?) are so solicitous about the intelligence of their constituents that they give publishers so disposed every opportunity to steal novels describing the nobility and English persons of distinction; that tons of such novels have been sold annually in the West, a thousand to one of the ‘author called Roe.’

“The simple truth in the case is that in spite of this immense and cheap competition, my novels have made their way and are being read among multitudes of others. No one buys or reads a book under compulsion; and if any one thinks that the poorer the book the better the chance of its being read by the American people, let him try the experiment. When a critic condemns my books, I accept that as his judgment; when another critic and scores of men and women, the peers of the first in cultivation and intelligence, commend the books, I do not charge them with gratuitous lying. My one aim has become to do my work conscientiously and leave the final verdict to time and the public. I wish no other estimate than a correct one; and when the public indicate that they have had enough of Roe, I shall neither whine nor write.”

_____

If you are interested in learning more about E.P. Roe, check out my article in the new issue (4.2) of Curtana: Sword of Mercy which was published online just last week.

Are you a skilled reader? Do you pride yourself on possessing a knack for making sense of challenging prose?

Are you a skilled reader? Do you pride yourself on possessing a knack for making sense of challenging prose?