If you are like me, you could benefit from a rich, genuine laugh right about now. Las year was stressful on all of us, and many are wary the new year may not be dramatically better.

For many of us, humor is an integral part of our lives. In our extended family, it is an ever ready tool for lifting the spirits of others. Just the other day our son and his six-year-old son dropped by, and as they entered the front door I said, “enter, most welcome king and prince.” Without missing a proverbial beat, my grandson responded, “I’m the king, and he’s the prince.” It was a hilarious, spontaneous moment. My wife and I are deeply blessed because our lives are filled with these moments.

We have all heard about the healing powers of laughter. One Mayo Clinic article on the subject, “Stress Relief from Laughter? It’s No Joke,” lists a number of short- and long-term benefits. For example:

Laughter enhances your intake of oxygen-rich air, stimulates your heart, lungs and muscles, and increases the endorphins that are released by your brain. . . . [It can] improve your immune system. Negative thoughts manifest into chemical reactions that can affect your body by bringing more stress into your system and decreasing your immunity.

By contrast, positive thoughts can actually release neuropeptides that help fight stress and potentially more-serious illnesses. [And laughter can] relieve pain . . . by causing the body to produce its own natural painkillers.

Since laughter has indisputable mental—and physical—benefits, promoting it is a worthwhile avocation. That effort is complicated by the fact our individual sense(s) of humor differ significantly. For example, some people find slapstick humor wildly funny. I find it funny (in the sense of “odd”), that they consider it witty.

On the other hand, some people appreciate the “subtleties” of so-called British humor. Many of my relatives have never understood how much I have enjoyed Monty Python. To them, the Python approach is bizarre and unpalatable. Meanwhile, they enjoyed the clumsy stumblings of Jerry Lewis.*

Ricky Gervais, an English comedian who has met great success on both sides of the pond, wrote an interesting piece for Time. He offers very thoughtful observations on “The Difference Between American and British Humour.” Having lived in the United Kingdom, and counting some Brits as friends today, the following comment rings true with me.

There’s a received wisdom in the U.K. that Americans don’t get irony. This is, of course, not true. But what is true is that they don’t use it all the time. It shows up in the smarter comedies but Americans don’t use it as much socially as Brits.

We use it as liberally as prepositions in every day speech. We tease our friends. We use sarcasm as a shield and a weapon. We avoid sincerity until it’s absolutely necessary. We mercilessly [verbally assault] people we like or dislike basically.

And ourselves. This is very important. Our brashness and swagger is laden with equal portions of self-deprecation. This is our license to hand it out.

Perhaps my affinity for British humor comes from a flaw in my personal psyche, I mean, an innate appreciation for irony.

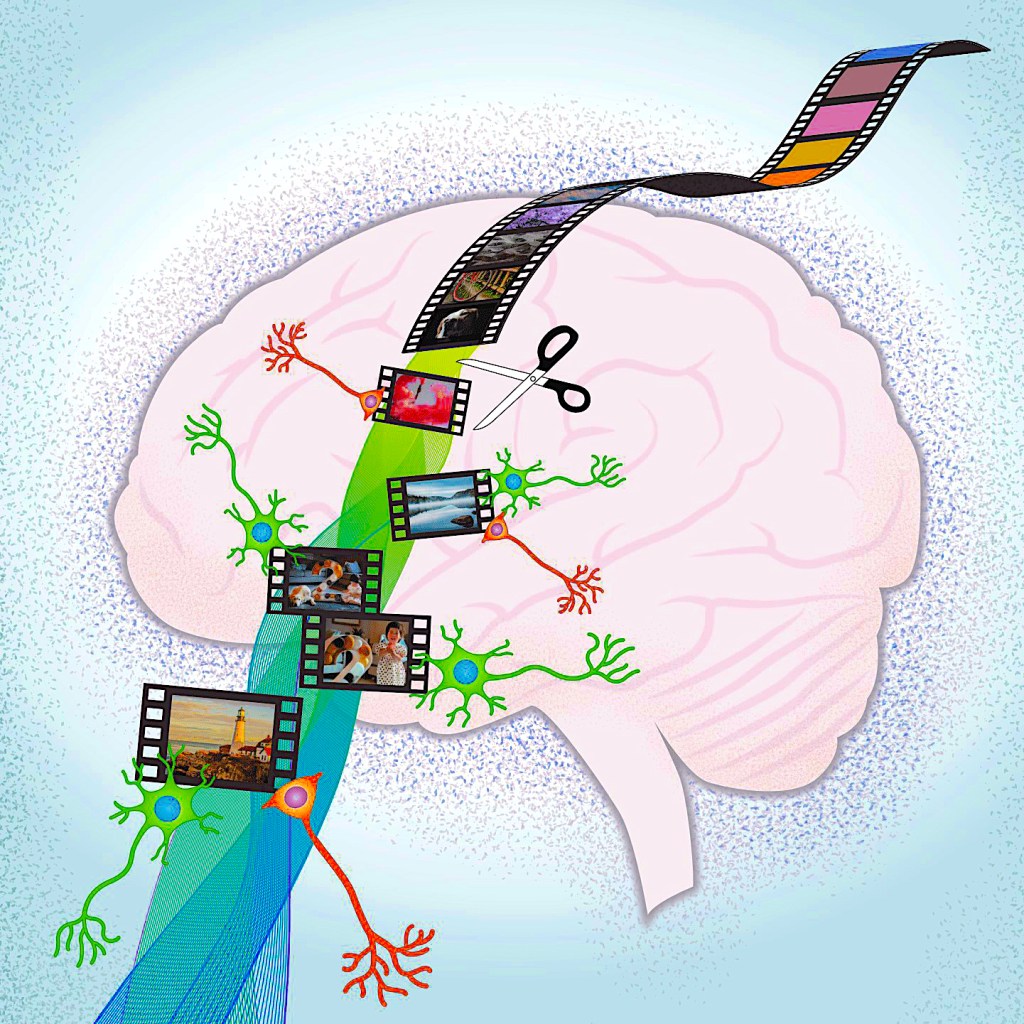

Another consideration is whether laughter is genuine or feigned. The latter presumably produces no positive results. Researchers in Japan conducted some laughter studies. One professor noted that honest laughter reaches down to a person’s diaphragm. He devised a machine to measure it.

Sensors placed near the diaphragm transmit waves to a computer screen, and these waves apparently reflect not only the intensity of a subject’s laughter but also its sincerity. A genuine laugh, straight from the heart, weighs in at 5 or more “aHs” per second –the “aH” (read “aha” in Japanese) being the unit of measurement Kimura devised in his quest to quantify laughter. Fake laughter makes no waves. The sensors ignore it, and the graph-lines on the screen remain unmoved.

Most of us, I suspect, can usually tell the difference between sincere responses, be they simple chuckles or raucous belly laughs, and the fake stuff. Fortunately, the inauthentic laughter is rarely malicious. An interesting dissertation entitled “The Meaningless Laugh,” explores laughter’s use to ease tension and “cover-up,” or mask, true opinions. It seems to me that insincere laughter has much in common with “white lies.”

Humor in the Life of C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis had a healthy sense of humor. Laughter abounded at gatherings of the Inklings. In light of Gervais’ comment about the British propensity for “teasing our friends,” check out “C.S. Lewis Compared J.R.R. Tolkien to What?”

Our sense of humor is shaped and refined (or dulled) throughout our lives. An interesting letter from 1914, before Lewis was scarred in the trenches of the First World War, reveals his entertainment preferences as a young man.

Last week I was up with these people to the Coliseum: and, though of course (which by the way I see no prospect of) I had sooner have gone to some musical thing, yet I enjoyed myself. The Russian Ballet–and especially the music to it–was magnificent, and G.P. Huntley* in a new sketch provoked some laughter.

The rest of the show trivial & boring as music halls usually are. At ‘Gastons’ however, I have no lack of entertainment, having been recently introduced to Chopin’s Mazurkas, & Beethoven’s ‘Sonate Pathétique.’

The mature Lewis made a profound observation about humor in Reflections on the Psalms.

A little comic relief in a discussion does no harm, however serious the topic may be. (In my own experience the funniest things have occurred in the gravest and most sincere conversations.)

I have found this to be true in my own life and ministry. In the words of the Mayo Clinic piece, “Laughter can also make it easier to cope with difficult situations. It also helps you connect with other people” even during the most trying of times.

Can Laughter Be Dangerous?

We all recognize that when humor is pursued at the expense of others, it is often destructive. Sarcasm is a dangerous, and often cruel, weapon. Healthy laughter, though, possesses a divine quality.

Laughter can, in fact, be such a positive thing that even the Tempter Screwtape⁂ warns his protégé to undermine it. (Remember, when reading Screwtape, that since Screwtape, the fictional writer of the infernal advice, serves the Devil, and thus the language is reversed.)

I am specially glad to hear that the two new friends have now made [your patient] acquainted with their whole set. All these, as I find from the [infernal] record office, are thoroughly reliable people; steady, consistent scoffers and worldlings who without any spectacular crimes are progressing quietly and comfortably towards Our Father’s house.

You speak of their being great laughers. I trust this does not mean that you are under the impression that laughter as such is always in our favour. The point is worth some attention. I divide the causes of human laughter into Joy, Fun, the Joke Proper, and Flippancy.

You will see the first among friends and lovers reunited on the eve of a holiday. Among adults some pretext in the way of Jokes is usually provided, but the facility with which the smallest witticisms produce laughter at such a time shows that they are not the real cause. What that real cause is we do not know.

Something like it is expressed in much of that detestable art which the humans call Music, and something like it occurs in Heaven—a meaningless acceleration in the rhythm of celestial experience, quite opaque to us. Laughter of this kind does us no good and should always be discouraged. Besides, the phenomenon is of itself disgusting and a direct insult to the realism, dignity, and austerity of Hell (The Screwtape Letters).

As to whether or not laughter can nudge a person towards a negative end, Screwtape singles out flippancy.

But flippancy is the best of all. In the first place it is very economical. Only a clever human can make a real Joke about virtue, or indeed about anything else; any of them can be trained to talk as if virtue were funny. Among flippant people the Joke is always assumed to have been made. No one actually makes it; but every serious subject is discussed in a manner which implies that they have already found a ridiculous side to it.

If prolonged, the habit of Flippancy builds up around a man the finest armour-plating against the Enemy that I know, and it is quite free from the dangers inherent in the other sources of laughter. It is a thousand miles away from joy: it deadens, instead of sharpening, the intellect; and it excites no affection between those who practise it (The Screwtape Letters).

Forewarned about the potential pitfalls of unhealthy humor, we can choose to avoid it. Meanwhile, we can rejoice with laughter that our Creator has bestowed upon us the ability to laugh.

C.S. Lewis celebrated this gift in his echo of our own creation in the story of Narnia’s birth. From the very first day, laughter was meant to resound throughout the world.

“Creatures, I give you yourselves,” said the strong, happy voice of Aslan. “I give to you forever this land of Narnia. I give you the woods, the fruits, the rivers. I give you the stars and I give you myself. The Dumb Beasts whom I have not chosen are yours also. Treat them gently and cherish them but do not go back to their ways lest you cease to be Talking Beasts. For out of them you were taken and into them you can return. Do not so.”

“No, Aslan, we won’t, we won’t,” said everyone. But one perky jackdaw added in a loud voice, “No fear!” and everyone else had finished just before he said it so that his words came out quite clear in a dead silence; and perhaps you have found out how awful that can be—say, at a party.

The Jackdaw became so embarrassed that it hid its head under its wing as if it were going to sleep. And all the other animals began making various queer noises which are their ways of laughing and which, of course, no one has ever heard in our world.

They tried at first to repress it, but Aslan said: “Laugh and fear not, creatures. Now that you are no longer dumb and witless, you need not always be grave. For jokes as well as justice come in with speech.”

So they all let themselves go. And there was such merriment that the Jackdaw himself plucked up courage again and perched on the cab-horse’s head, between its ears, clapping its wings, and said: “Aslan! Aslan! Have I made the first joke? Will everybody always be told how I made the first joke?”

“No, little friend,” said the Lion. “You have not made the first joke; you have only been the first joke.” Then everyone laughed more than ever; but the Jackdaw didn’t mind and laughed just as loud till the horse shook its head and the Jackdaw lost its balance and fell off, but remembered its wings (they were still new to it) before it reached the ground.

Laughter is a gift from God. I believe it is one of his best.

* The warm appreciation of comedian Jerry Lewis (1926-2017) by the French has always been a mystery to me. Talk about different ways to view humor. An interesting discussion of that enigmatic fact is found in “Why France Understood Jerry Lewis as America Never Did.”

Jerry Lewis was always a subject of a deep trans-Atlantic misunderstanding, one that triggered sarcasm in the United States, and bewilderment in France. While some Americans felt embarrassed by this contortionist comic, the French embraced Mr. Lewis’s humor as both an abstract art and social satire of American life.

Americans mocked the French for falling for this crass clown, while the French couldn’t understand why Mr. Lewis’s genius was not obvious to his compatriots.

⁑ George Patrick Huntley (1868–1927) was an Irish actor, known for comic performances in the theatre and the music halls.

⁂ The fictional author of C.S. Lewis’ book, The Screwtape Letters. Screwtape, the senior Tempter serves his master, the Devil. He refers to him as “Our Father Below,” accordingly.

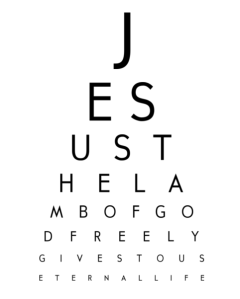

The graphic above comes from the blog of a very talented writer and producer. Mitch Teemley included in a recent post at The Power of Story. I agree with my friend that “laughter has healing properties.” If you believe the same, you absolutely need to spend a few minutes reading his hilarious post.

The world’s oldest man just died—and I’m not looking forward to ever becoming one of his successors. I mean, I understand the sentiments of non-Christians who quip that any day on this side of the grass is a good one, but I would only be interested in staying around here that long if I still had a keen mind and good health.

The world’s oldest man just died—and I’m not looking forward to ever becoming one of his successors. I mean, I understand the sentiments of non-Christians who quip that any day on this side of the grass is a good one, but I would only be interested in staying around here that long if I still had a keen mind and good health.