One of the pivotal events in the history of God’s grace is found in the Torah account of a dream. Jacob was the heir of Abraham, through whom the Lord promised to redeem the world. But Jacob was far from noble.

Nevertheless, because of the Lord’s mercy (the same mercy he offers to us), he forgave Jacob and promised to bless his descendants. In his dream, Jacob saw a ladder extending from earth all the way to heaven. “And behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it!” (Genesis 28).

This dynamic connection between heaven and earth reveals God’s constant concern for his creation. Some, such as Martin Luther, have seen in the dream a foreshadowing of the Incarnation itself.

This ladder or stairway can be interpreted in a variety of ways. One thing it is not, however, is a guide to human ascent from our fallen world to the presence of our Creator. (The Lord is the one who comes to us.)

Having acknowledged that the dream’s purpose is not to model sanctification or individual spiritual ascent, it is easy to see why the metaphor of ladders, and the action of climbing, give way to other applications.

The most vivid contemporary example comes in the form of a Christian spiritual entitled “We are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder.” A number of versions of the lyrics exist. This is quite unsurprising since it began as part of an oral tradition. According to one website devoted to spirituals, the following lyrics are typical.*

We are climbing Jacob’s ladder

We are climbing Jacob’s ladder

We are climbing Jacob’s ladder

Soldier of the Cross

Ev’ry round goes higher ‘n’ higher

Ev’ry round goes higher ‘n’ higher

Ev’ry round goes higher ‘n’ higher

Soldier of the Cross

Brother do you love my Jesus

Brother do you love my Jesus

Brother do you love my Jesus

Soldier of the Cross

If you love him why not serve him

If you love him why not serve him

If you love him why not serve him

Soldier of the Cross

While there are longer versions, this one aptly illustrates how the metaphor of the ladder—in this case, explicitly Jacob’s ladder—offered a powerful image of deliverance. Climbing the ladder with Jesus, was tantamount to experiencing deliverance from the ills of this world.

America’s Library of Congress offers a useful page which describes “African American Gospel music [as] a form of euphoric, rhythmic, spiritual music rooted in the solo and responsive church singing of the African American South.” They add that “its development coincided with—and is germane to—the development of rhythm and blues.” The site offers links to four 1943 recordings of spirituals. None of these, however, is the hymn we are discussing.

“We are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder” was one of the earliest spirituals to be widely adopted by the interracial faith community. It is familiar in many denominations, and was recently sung in my own Lutheran congregation. Hymnary.org states the song has been “published in 79 hymnals.” Even those who consider themselves unfamiliar with the hymn often recognize its rousing refrain: “Rise and shine and give God the glory, glory, Soldiers of the Cross.”

The talented Paul Robeson recorded the hymn on a number of his albums. The inspiring rendition by scholar Bernice Johnson Reagon was included in Ken Burn’s documentary, The Civil War.

C.S. Lewis and the Spiritual Ladder

The ladder offers such a convenient analogy for growth or spiritual maturation that others have also applied it in this manner. The ladders inspired by Jacob’s dream include the following two which continue to influence Christian disciples today, even though they were written many centuries ago. The second of these was considered by C.S. Lewis to be one of the works of faith influential in his life.

John Climacus (579-649) was a Christian teenager when he entered the monastic life at the foot of Mount Sinai. He soon earned the respect of his elders in that barren land. In the words of Fathers of the Desert, “in this ascetic seclusion he became ripe for the designs of God.”

The abbot of a monastery on the Red Sea requested guidance on the ascetic life to use with his monks. John responded with The Ladder of Divine Ascent. You can download a modern translation of this priceless work here. While the treatise was written specifically to guide monastics in their spiritual growth, many other Christians have also found its wisdom helpful in their own, non-monastic settings.

John introduces the virtue of obedience with two vivid images used by the Apostle Paul, the athlete in training and the armor of God.

Our treatise now appropriately touches upon warriors and athletes of Christ [and the manner in which] the holy soul steadily ascends to heaven as upon golden wings. And perhaps it was about this that he who had received the Holy Spirit sang: Who will give me wings like a dove? And I will fly by activity, and be at rest by contemplation and humility.

But let us not fail, if you agree, to describe clearly in our treatise the weapons of these brave warriors: how they hold the shield of faith in God and their trainer, and with it they ward off, so to speak, every thought of unbelief and vacillation; how they constantly raise the drawn sword of the Spirit and slay every wish of their own that approaches them; how, clad in the iron armour of meekness and patience, they avert every insult and injury and missile.

And for a helmet of salvation they have their superior’s protection through prayer. And they do not stand with their feet together, for one is stretched out in service and the other is immovable in prayer.

The following passage will be of particular interest to Christian writers. John advises those drawing closer to God to maintain a journal of their progress and insights. I offer it within its wise context.

Let all of us who wish to fear the Lord struggle with our whole might, so that in the school of virtue we do not acquire for ourselves malice and vice, cunning and craftiness, curiosity and anger. For it does happen, and no wonder!

As long as a man is a private individual, or a seaman, or a tiller of the soil, the King’s enemies do not war so much against him. But when they see him taking the King’s colours, and the shield, and the dagger, and the sword, and the bow, and clad in soldier’s garb, then they gnash at him with their teeth, and do all in their power to destroy him. And so, let us not slumber.

I have seen innocent and most beautiful children come to school for the sake of wisdom, education and profit, but through contact with the other pupils they learn there nothing but cunning and vice. The intelligent will understand this.

It is impossible for those who learn a craft whole-heartedly not to make daily advance in it. But some know their progress, while others by divine providence are ignorant of it. A good banker never fails in the evening to reckon the day’s profit or loss. But he cannot know this clearly unless he enters it every hour in his notebook. For the hourly account brings to light the daily account.

In the fourteenth century, an Augustinian mystic in England wrote a book called The Scale [Ladder] of Perfection.” Walter Hilton (c. 1340-1396) provides spiritual exercises requested by a woman adopting life as an anchoress.⁑ You can download a free copy of Evelyn Underhill’s 1923 edition of Hilton’s counsel at Internet Archive.

In 1940, C.S. Lewis wrote to Roman Catholic monk Bede Griffiths in response to the latter’s question about his familiarity with Hilton’s work. “Yes, I’ve read the Scale of Perfection with much admiration. I think of sending the anonymous translator a list of passages that he might reconsider for the next edition.” That same decade Lewis’ collected correspondence reveals he recommended the title to at least two individuals.

Of greatest interest to students of C.S. Lewis will be his mention of the medieval treatise in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy. Here the great author describes his worldly understanding of prayer served as a terrible stumbling block to his faith.

To these nagging suggestions my reaction was, on the whole, the most foolish I could have adopted. I set myself a standard. No clause of my prayer was to be allowed to pass muster unless it was accompanied by what I called a “realization,” by which I meant a certain vividness of the imagination and the affections.

My nightly task was to produce by sheer will power a phenomenon which will power could never produce, which was so ill-defined that I could never say with absolute confidence whether it had occurred, and which, even when it did occur, was of very mediocre spiritual value.

If only someone had read to me old Walter Hilton’s warning that we must never in prayer strive to extort “by maistry” what God does not give! But no one did; and night after night, dizzy with desire for sleep and often in a kind of despair, I endeavored to pump up my “realizations.” The thing threatened to become an infinite regress.

One began of course by praying for good “realizations.” But had that preliminary prayer itself been “realized”? This question I think I still had enough sense to dismiss; otherwise it might have been as difficult to begin my prayers as to end them.

How it all comes back! The cold oilcloth, the quarters chiming, the night slipping past, the sickening, hopeless weariness. This was the burden from which I longed with soul and body to escape. It had already brought me to such a pass that the nightly torment projected its gloom over the whole evening, and I dreaded bedtime as if I were a chronic sufferer from insomnia. Had I pursued the same road much further I think I should have gone mad.

This ludicrous burden of false duties in prayer provided, of course, an unconscious motive for wishing to shuffle off the Christian faith; but about the same time, or a little later, conscious causes of doubt arose.

David Downing, co-director of the Wade Center wrote an excellent essay entitled “Into the Region of Awe: Mysticism in C.S. Lewis” which describes in the broader context what C.S. Lewis wrote in Surprised by Joy.

Note for example a passage in Surprised by Joy in which Lewis discusses the loss of his childhood faith while at Wynyard School in England. He explains that his schoolboy faith did not provide him with assurance or comfort, but created rather self-condemnation.

He fell into an internalized legalism, such that his private prayers never seemed good enough. He felt his lips were saying the right things, but his mind and heart were not in the words. Lewis adds “if only someone had read me old Walter Hilton’s warning that we must never in prayer strive to extort ‘by maistry’ [mastery] what God does not give.”

This is one of those casual references in Lewis which reveals a whole other side to him which may surprise those who think of him mainly as a Christian rationalist. “Old Walter Hilton” is the fourteenth-century author of a manual for contemplatives called The Scale of Perfection. This book is sometimes called The Ladder of Perfection, as it presents the image of a ladder upon which one’s soul may ascend to a place of perfect unity and rest in the Spirit of God . . . [passage continued in footnotes]. ⁂

We’ve considered four separate ladders today. Despite their differences, they all share a common trait—they are meaningful to those who are earnest about growing in the faith. Whether slave or free, wise or simple, or hermit or cosmopolitan—each of these ladders affirms eternal truths.

Underhill described Hilton’s motivation for writing in this way: “It is for those who crave for this deeper consciousness of reality, and feel this impulse to a complete consecration, that Hilton writes.” I believe this is true for the authors of each of these four treasures.

* The following, simpler version appears to follow an earlier tradition. A musical accompaniment for this example can be found in The Books of American Negro Spirituals. The author, James Weldon Johnson (1876-1938), provides a rich and earnest introduction to the book, originally published in two volumes. He expresses his hope that collection “will further endear these sons to those who love Spirituals, and will awaken an interest in many others.”

We am clim’in’ Jacob’s ladder

We am clim’in’ Jacob’s ladder

We am clim’in’ Jacob’s ladder

Soldiers of the cross

O

Ev’ry roun’ goes higher, higher

Ev’ry roun’ goes higher, higher

Ev’ry roun’ goes higher, higher

Soldiers of the cross

⁑ An anchoress (or anchorite) was a religious woman (or man) who would often be walled off in their monastic cell near a church, to foster their life of prayer by freeing them from interruption.

⁂ Downing’s discussion of C.S. Lewis’ reference to Walter Hinton’s insights on prayer is so valuable that I am compelled to offer the rest of it here. You can read the entire essay via the link on the article’s title.

The passage about “maistry” Lewis wished he’d known as a boy comes early in The Scale of Perfection, a section about different kinds of prayer, including liturgical prayers, spontaneous prayers, and “prayers in the heart alone” which do not use words.

Hilton’s advice for people “who are troubled by vain thoughts in their prayer” is not to feel alone. He notes it is very common to be distracted in prayer by thoughts of what “you have done or will do, other people’s actions, or matters hindering or vexing you.”

Hilton goes on to explain that no one can keep fully the Lord’s command to love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, strength, and mind. The best you can do is humbly acknowledge your weakness and ask for mercy. However badly one’s first resolve fades, says Hilton, you should not get “too fearful, too angry with yourself, or impatient with God for not giving you savor and spiritual sweetness in devotion.”

Instead of feeling wretched, it is better to leave off and go do some other good or useful work, resolving to do better next time. Hilton concludes that even if you fail in prayer a hundred times, or a thousand, God in his charity will reward you for your labor. Walter Hilton was the canon of a priory in the Midlands of England and an experienced spiritual director of those who had taken monastic vows. His book is full of mellow wisdom about spiritual growth, and Lewis considered it one of “great Christian books” that is too often neglected by modern believers.

Hilton’s recurring theme—do what you know to be right and don’t worry about your feelings—is one that appears often in Lewis’s own Christian meditations. But, alas, Lewis as a boy did not have the benefit of Hilton’s advice.

In those boyhood years at Wynyard, he was trapped in a religion of guilt, not grace. More and more he came to associate Christianity with condemnation of others, as in Northern Ireland, or condemnation of oneself, for not living up to God’s standards.

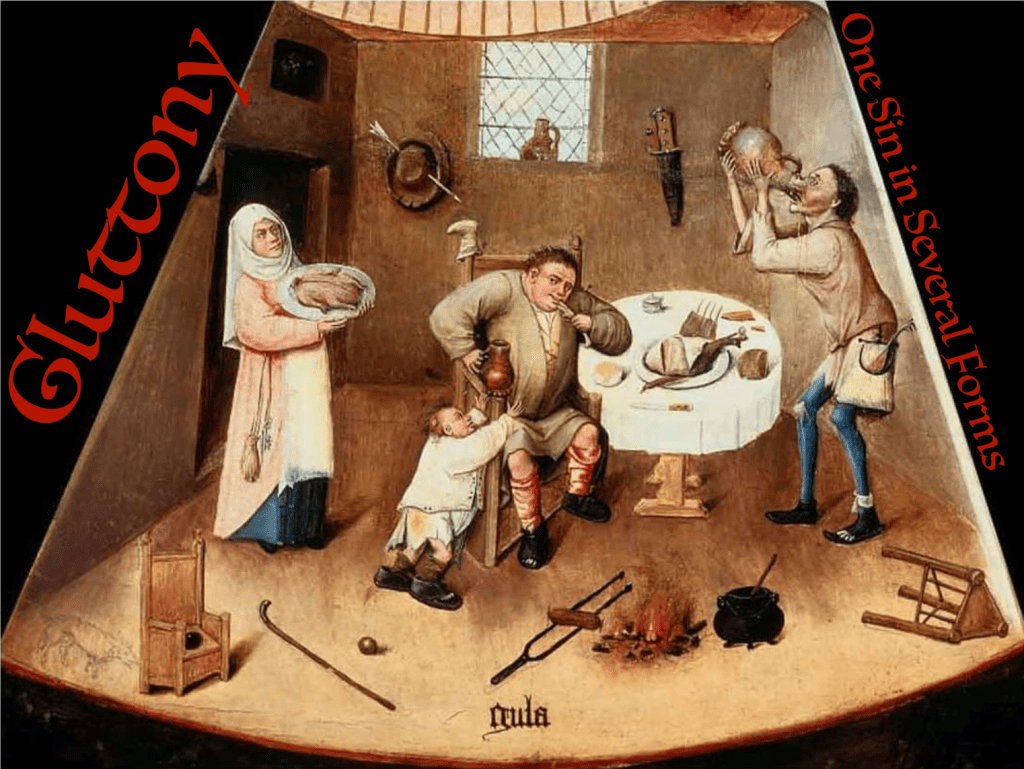

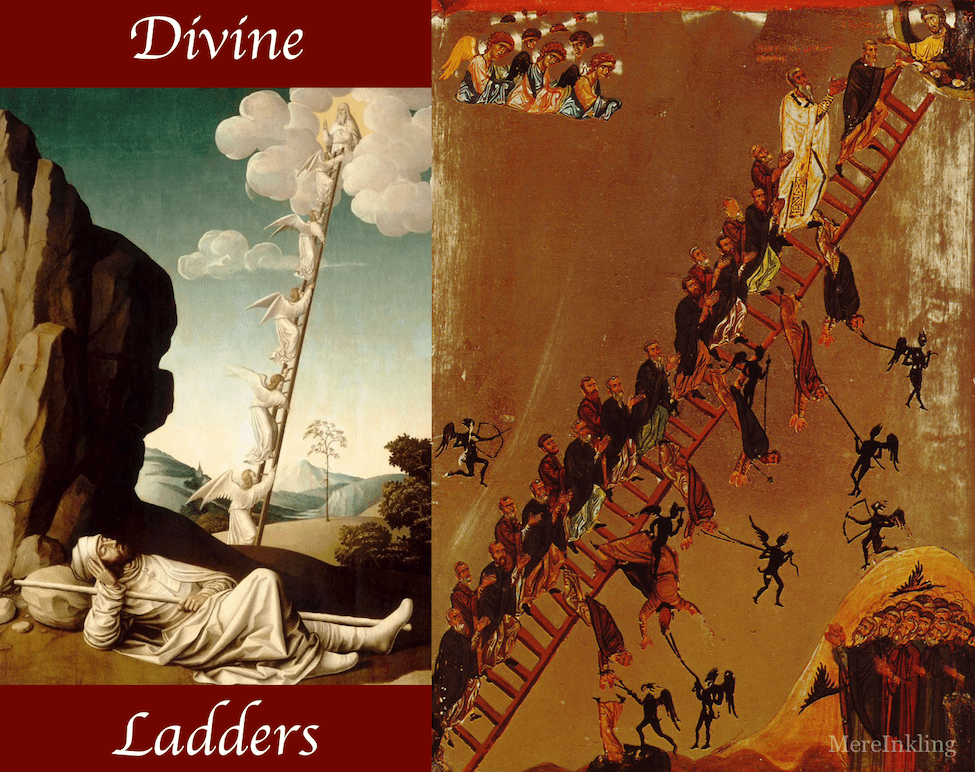

A Note on the Illustration

Nicolas Dipre was a French early Renaissance painter, who flourished 1495-1532. His painting of Jacob’s Ladder portrays the biblical account of the Jewish patriarch’s dream. The icon Ladder of Divine Ascent was painted four centuries earlier by an anonymous iconographer. It is from Saint Catherine’s Monastery beside Mount Sinai, and portrays the ascent of saints in the pursuit of holiness. While fallen angels (devils) seek to drag them from the path, John Climacus leads other in the path to heaven.