Today’s lesson will be . . . wait a second, we don’t post “lessons” here at Mere Inkling. We hope many of our columns are thought-provoking, and it would be nice to think a moderate share of them are entertaining.

However, if there’s any learning to be done, it’s incidental.

This post, though, verges on being educational. It addresses a subject readers and writers encounter every day. A subject about which there is frequent disagreement.

The question of which words should be capitalized is a major inspiration for writing Style Guides. (Oh no, I probably shouldn’t have capitalized that genre title.)

I am not alluding here to the style guides that major companies invest big bucks in designing to present their preferred image to the world. You can see some stunning examples of those here.

I’m interested in literary style guides. If you’ve ever written for publication, you’re likely familiar with the type of single sheet guidelines magazines create for prospective writers. The last thing you want, after wetting the manuscript’s pages with sweat and tears, is to have it discarded without review because you violated some editor’s pet peeves.

A standard stylebook that was required knowledge back in my college Journalism* days is the AP Stylebook. AP, of course, stands for “Associated Press.” And, where would the world of Academia be without the Chicago Manual of Style?

An even older stylebook that continues to play an important role is The Elements of Style written by William Strunk, Jr. Modern editions are attributed to “Strunk and White,” since it was revised and enlarged in 1959 by E.B. White. (Yes, that E.B. White, who authored Charlotte’s Web and other children’s classics.)

You can download a free copy of The Elements of Style at the Internet Archives, but it might be a tad risky to rely on the style described in Strunk’s first edition, since it was penned during the First World War.

It should be noted that not everyone is quite as enamored with the book as Mr. and Mrs. William Strunk, Sr. probably were. The author of one particularly haughty essay alleges that “the book’s contempt for its own grammatical dictates seems almost willful, as if the authors were flaunting the fact that the rules don’t apply to them.”

Christians & Capitalization

Religious writers vary in their capitalization of particular words. This variation crosses faith boundaries and is sometimes referred to as “reverential capitalization.”

The most obvious example in English literature is the question of whether or not the divine pronoun should be capitalized. This issue is encountered when a pronoun refers to God. The New American Standard Bible translation, for example, follows the traditional practice.

Seek the Lord and His strength; Seek His face continually. Remember His wonders which He has done, His marvels and the judgments uttered by His mouth . . . (Psalm 105:4-5)

My own practice of not capitalizing divine pronouns has occasionally scandalized members of critique groups to which I have belonged.*** A very few appear incapable of recognizing it’s a grammatical consideration, rather than a spiritual one. (Sadly, this sort of reaction often presages an individual’s departure from the writing support community, even when they are precisely the type of person who could best benefit from joining in.)

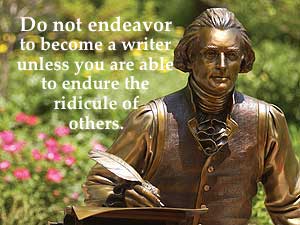

It should come as no surprise to learn that C.S. Lewis capitalized divine pronouns. Typical of his writing is this profound excerpt from Weight of Glory.

I read in a periodical the other day that the fundamental thing is how we think of God. By God Himself, it is not! How God thinks of us is not only more important, but infinitely more important.

Indeed, how we think of Him is of no importance except insofar as it is related to how He thinks of us. It is written that we shall “stand before” Him, shall appear, shall be inspected. The promise of glory is the promise, almost incredible and only possible by the work of Christ, that some of us, that any of us who really chooses, shall actually survive that examination, shall find approval, shall please God.

To please God… to be a real ingredient in the divine happiness… to be loved by God, not merely pitied, but delighted in as an artist delights in his work or a son—it seems impossible, a weight or burden of glory which our thoughts can hardly sustain. But so it is.

The Christian Writer’s Manual of Style acknowledges that “The capitalization of pronouns referring to persons of the Trinity has been a matter of debate for many decades.” They go so far as to state that doing so can impede our ability to communicate with “modern readers.”

Because capitalizing the deity pronoun, as well as a vast number of other religious terms, was the predominant style in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century publishing, it gives a book, at best, a dated, Victorian feel, and at worst, an aura of complete irrelevance to modern readers.

Capitonyms are a subgroup of homonyms. Their meaning changes on the basis of whether or not they are capitalized. A simple example would be distinguishing between a farmer’s concern for the quality of the earth in his fields and his regard for the planet on which he resides. Speaking of the Earth, we talk about the moons circling Jupiter, but all recognize that the Moon is the satellite that orbits 1.28 light-seconds above the surface of our planet.

In some Christian traditions, certain doctrines and events are capitalized while the very same words are not capitalized in a different sense. For example, many Christians would consider the following sentence correct.

It was the Resurrection of the only begotten Son of God that prepares the way for the resurrection of all those who take up their own cross and follow him.

The obvious difference is that the first use of the word refers to the singular miraculous event that transpired on Easter, while the latter points to its generalized definition.

In my most recent post I referred to the Gospels, as a genre unique to the writings about the life and significance of Jesus of Nazareth. As literary works, individually or collectively, the Gospels are capitalized, even when they do not include their full title [e.g. the Gospel According to Luke]. Most writers do not, however, capitalize gospel when used in a general sense, such as “every modern-day guru claims to possess a gospel of their own.” Just to make matters more interesting, some traditions capitalize Gospel when it refers to God’s love as embodied in the sacrificial death of Christ for the forgiveness of humanity’s sin.

One witty blogger chides the Church*** for over-capitalization.

I may just be cynical, and I’m definitely a literary snob, but it seems sometimes as though American Christians capitalize words related to Christianity just to make them seem holier.

For example, hymns and worship songs never refer to God and his mercy. It’s evidently more holy to capitalize the divine pronoun and refer to God and His mercy.

And if we capitalize mercy, which is a divine attribute, it makes the hymn or worship song even holier. I mean, God and His Mercy is clearly holier than God and his mercy, isn’t it?

So sermons are full of Grace, Goodness, Predestination, Prophecy, Agape, Apostles, Epistles, Pre-Millennialism, Mid-Millennialism, Post-Millennialism and the Millennium Falcon. All right, maybe not that last one.

Additional Insights from Lewis

One online writer offers a curious contrast between Lewis and e.e. cummings.

The writers who taught me the exponential value of capitalization: C.S Lewis and e.e. cummings. You know the rules of capitalization . . . Lewis and Cummings allow the capital letter to go deeper in its responsibility in communicating to the reader. . . .

For Lewis, capitalization often serves as a signpost of spiritual realities. He uses it to name a reality [as in The Screwtape Letters:] “We of course see the connecting link, which is Hatred.”

The most disorienting example of capitalization by Screwtape is his reference to God as the “Enemy.” It is a startling reversal of the true enemy, whose various names are commonly capitalized: Lucifer, Satan, Adversary, the Beast, Father of Lies and Evil One. Not to mention devils, which is sometimes used to refer to evil spirits (also known as demons or fallen angels), in contrast to the Devil himself who is also known by the aforementioned titles.

With so many alternatives when it comes to capitalization, the key is to follow the example of C.S. Lewis. It’s two-fold. First, have a reason why you select the option you do. Then, be consistent. Most readers readily adapt to different usages. What they can’t forgive, is inconsistency and literary chaos.

_____

* “Journalism” is capitalized here because it refers specifically to an academic college and degree program in many universities.

** The conservative Lutheran denomination to which I belong includes in its Stylebook for Authors and Editors the following guidance.

Gospel Uppercase when referring to the Gospel message of salvation in Jesus Christ. Also uppercase when referring to one of the four New Testament Gospels.

The second rule indicates that one would use lowercase to refer to pseudepigraphical or heretical gospels. However, if the entire title of the text is used—precisely because it is a text, it would be capitalized (e.g. the Gospel of Thomas).

*** My wife occasionally finds time in her hectic schedule to proofread my posts before publication. (These would be the ones that appear without mistakes.) Well, Delores kindly pointed out just now that she too is scandalized by my irreverent failure to capitalize divine pronouns. After forty years of mostly-blissful marriage you would think she might have overlooked saying that… but, then again, when they’re truly scandalized how could someone be expected to remain silent?

**** I prefer to capitalize “Church” when it refers to the whole Body of Christ, but not when it references a congregation, denomination or a building . . . unless it’s part of a formal name such as the Church of the Nativity, in Bethlehem.

Nearly everyone has a sobriquet, even those who don’t know what it is.

Nearly everyone has a sobriquet, even those who don’t know what it is.