If you like to expand your vocabulary while opening up your mind with profound insights, search no farther than C.S. Lewis.

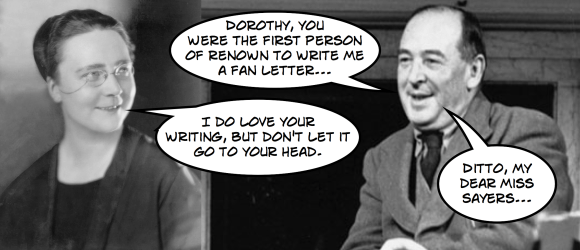

The celebrated Oxbridge professor possessed a great respect for words. Like his friend J.R.R. Tolkien, he believed they should never be summarily detached from the history which imbues them with meaning. In “Studies in Words,” he describes the poverty of such an approach.

I am sometimes told that there are people who want a study of literature wholly free from philology; that is, from the love and knowledge of words. Perhaps no such people exist. If they do, they are either crying for the moon or else resolving on a lifetime of persistent and carefully guarded delusion.

If we read an old poem with insufficient regard for change in the overtones, and even the dictionary meanings, of words since its date – if, in fact, we are content with whatever effect the words accidentally produce in our modern minds – then of course we do not read the poem the old writer intended. What we get may still be, in our opinion, a poem; but it will be our poem, not his. If we call this tout court [too short or shallow] “reading” the old poet, we are deceiving ourselves. If we reject as “mere philology” every attempt to restore for us his real poem, we are safeguarding the deceit.

Of course any man is entitled to say he prefers the poems he makes for himself out of his mistranslations to the poems the writers intended. I have no quarrel with him. He need have none with me. Each to his taste.

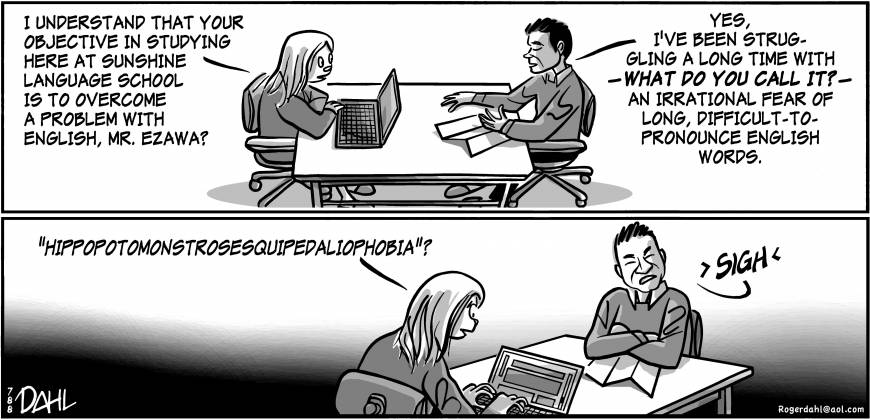

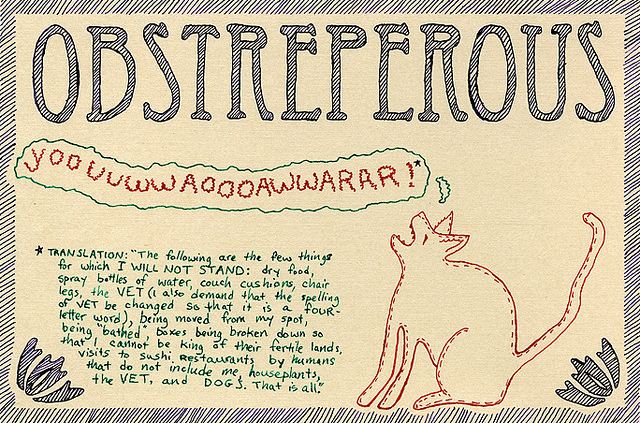

If you too are a logophile, a lover of words, there’s no need to hide it. Well, with a single exception. Like everyone else, I find it off-putting when I run into people who learn complex new words simply with the goal of using them in order to “impress” others.

It amazes me how some individuals who consider themselves quite intelligent, and wish to advertise their brilliance, fail to comprehend that ostentatious speech elicits the opposite impression. [Don’t mistake my writing style where I intentionally use the fullest range of our shared vocabulary – which I believe enriches our reading and minds – with the vanity I’m describing. The latter insults readers when self-important posers attempt to intimidate others with words that are unlikely to be known by their audience.]

If you would like to read a satirical piece I wrote ridiculing this tactic, you can download “Mastering Inkling Erudition” at academia.edu. It appeared in CSL, published by the New York C.S. Lewis Society and is subtitled “Sounding Like an Expert Without Accumulating Multiple Ph.D.s.”

C.S. Lewis, of course, possessed no such pretentions. At least none I am aware of after his conversion to Christianity. His use of language is rich and satisfying. It is also instructive. I’ve lost count of the number of words to which Lewis introduced me.

One of my favorites, though I have never dared to use it, is “bathetic.” Upon reading this note from Merriam-Webster, I suspect you too may find it applicable to much that passes for contemporary literature.

When English speakers turned apathy into apathetic in the late 17th century, using the suffix -etic to turn the noun into the adjective, they were inspired by pathetic, the adjectival form of pathos, from Greek pathētikos.

People also applied that bit of linguistic transformation to coin bathetic. English speakers added the suffix -etic to bathos, the Greek word for “depth,” which in English has come to mean “triteness” or “excessive sentimentalism.” The result: the ideal adjective for the incredibly commonplace or the overly sentimental.

The word appears in The Abolition of Man, in which C.S. Lewis critiques the poor practices of some current authors of educational resources. I will italicize the specific text, but provide the full context because of its own merits.

[They] quote a silly advertisement of a pleasure cruise and proceed to inoculate their pupils against the sort of writing it exhibits. The advertisement tells us that those who buy tickets for this cruise will go ‘across the Western Ocean where Drake of Devon sailed,’ ‘adventuring after the treasures of the Indies,’ and bringing home themselves also a ‘treasure’ of ‘golden hours’ and ‘glowing colours.’

It is a bad bit of writing, of course: a venal and bathetic exploitation of those emotions of awe and pleasure which men feel in visiting places that have striking associations with history or legend. If [they] were to stick to their last and teach their readers (as they promised to do) the art of English composition, it was their business to put this advertisement side by side with passages from great writers in which the very emotion is well expressed, and then show where the difference lies.

They might have used Johnson’s famous passage from the Western Islands, which concludes: ‘That man is little to be envied, whose patriotism would not gain force upon the plain of Marathon, or whose piety would not grow warmer among the ruins of Iona.’ They might have taken that place in The Prelude where Wordsworth describes how the antiquity of London first descended on his mind with ‘Weight and power, Power growing under weight.’

A lesson which had laid such literature beside the advertisement and really discriminated the good from the bad would have been a lesson worth teaching. There would have been some blood and sap in it – the trees of knowledge and of life growing together. It would also have had the merit of being a lesson in literature . . .

And a Double Bonus: A New Word & a Psychological Disorder

A newly forged word is referred to as a neologism, and they can be fascinating. Modern technology has caused their number to explode. Some – think “crowdsourcing” or “app” – are now ubiquitous.

Word lovers sometimes invent words. These, of course, rarely if ever find their way into public discourse. Take this example from a letter a young C.S. Lewis penned to his friend Arthur Greeves in 1916.

I know quite well that feeling of something strange and wonderful that ought to happen, and wish I could think like you that this hope will someday be fulfilled. . . . Perhaps indeed the chance of a change into some world of Terreauty (a word I’ve coined to mean terror and beauty) is in reality in some allegorical way daily offered to us if we had the courage to take it.

One final caution. If you do decide to become a neologist, run your ideas by people you trust. I just discovered the American Psychological Association has linked one expression of the practice to serious mental disorders!

neologism (updated on 04/19/2018)

n. a newly coined word or expression. In a neurological or psychopathological context, neologisms, whose origins and meanings are usually nonsensical and unrecognizable (e.g., klipno for watch), are typically associated with aphasia or schizophrenia. – neologistic adj.