My wife and I love that phrase, and we often recall it when we encounter particularly over-strained (or “broken”) grammar. When I encountered it as the title of a book, I was unaware of its original source.

My wife and I love that phrase, and we often recall it when we encounter particularly over-strained (or “broken”) grammar. When I encountered it as the title of a book, I was unaware of its original source.

This is where I reveal that I wasn’t an American Lit major in college. (Well, regular readers probably figured that out long ago.)

I had never heard of Ring Lardner until today. (If you don’t recognize his name either, you needn’t feel embarrassed . . . he died eighty years ago.)

Lardner was a well regarded humorist who considered himself a sports writer. One of his satires was entitled The Young Immigrunts. It was a parody of a popular English book, The Young Visitors, which was allegedly written by a young girl.

The Young Immigrunts is fictitiously ascribed to Lardner’s son, Ringgold Wilmer Lardner, Jr. His son was only four, at the time. Later he would become a successful screenwriter, winning an Academy Award for the film M*A*S*H. He also wrote prolifically for the television series.

Perhaps Lardner Junior is best remembered as one of the Communist writers blacklisted in Hollywood. But we need not go into that, since his father was merely using his young son as a surrogate author for the work.

The book takes the form of the ramblings of a child, and its quaintness will appeal to many readers. You can download a copy of it here.

It’s not my own preferred genre, so I won’t be reading it in its entirety, but in small doses, I find it rather entertaining.

A little later who should come out on the porch and set themselfs ner us but the bride and glum [pictured above].

Oh I said to myself I hope they will talk so as I can hear them as I have always wandered what newlyweds talk about on their way to Niagara Falls and soon my wishs was realized.

Some night said the young glum are you warm enough.

I am perfectly comfertible replid the fare bride tho her looks belid her words what time do we arrive in Buffalo.

9 oclock said the lordly glum are you warm enough.

I am perfectly comfertible replid the fare bride what time do we arive in Buffalo.

9 oclock said the lordly glum I am afrade it is too cold for you out here.

Well maybe it is replid the fare bride and without farther adieu they went in the spacius parlers.

I wander will he be arsking her 8 years from now is she warm enough said my mother with a faint grimace.

The weather may change before then replid my father.

Are you warm enough said my father after a slite pause.

No was my mothers catchy reply.

And now the phrase that always makes me smile.

The lease said about my and my fathers trip from the Bureau of Manhattan to our new home the soonest mended. In some way ether I or he got balled up on the grand concorpse and next thing you know we was thretning to swoop down on Pittsfield.

Are you lost daddy I arsked tenderly.

Shut up he explained.

I am curious as to whether or not C.S. Lewis was acquainted with Lardner’s work. It doesn’t quite conform to his literary tastes, but Lewis was so widely read that I think it’s possible he was at least acquainted with who he was.

My research on the matter did produce an interesting juxtaposition between the two authors. I discovered it in a book by Sherwood Wirt, perhaps the last reporter to interview C.S. Lewis (for Decision magazine, of which he was editor). I was privileged to know “Woody,” so I enjoyed finding that he mentioned both men in his book I Don’t Know what Old is, But Old is Older than Me.

With twentieth century fiction we have to be quite selective. In limiting my comments to the American scene, I will pass by many of the great names of fiction — Henry James, Stephen Crane, Edith Wharton, Jack London, Theodore Dreiser, Ring Lardner, William Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis, Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, James Baldwin, John Steinbeck, Vladimir Nabokov, Norman Mailer, and Truman Capote.

While most of these are excellent writers, I doubt whether they have much to say to today’s older readers that would make life more pleasant, more interesting, or more fruitful in the closing stretches of life’s journey. Nor do I think that these authors have anything worthwhile to say about what lies beyond death. We might better spend our reading hours riding off into the sunset with Louis L’Amour or Zane Grey, rather than punish ourselves with a ghastly tale like In Cold Blood.

We old boys and girls have been around a long time. We know what the world is like. We know sleaze when we see it, and we don’t need contemporary authors to embellish it or explain it to us.

The reading tastes of the American public have been corrupted almost beyond redemption by blasphemy, vulgarity, and scatology, all for the sake of increased book sales to prurient minds. There are, however, many twentieth-century American novels worth reading, such as Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October, the Savannah quartet of Eugenia Price, and the Sebastian series of James L. Johnson, to name only a few.

Earlier in the century the Christian novels of Lloyd C. Douglas—The Magnificent Obsession, The Robe, and The Big Fisherman—inspired thousands of readers young and old, but no American has since matched his popular appeal.

The demand for detective fiction continues unabated, and no one needs my advice to read Agatha Christie. I would, therefore, limit my remarks to a reference to two British creations, G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown and Dorothy Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey, since both are written from Christian backgrounds. My two favorite Wimsey stories are Busman’s Honeymoon and The Nine Tailors.

In contrast there is a wealth of devotional literature that makes wonderful reading for older people. One can start with the sermons of D.L. Moody, Charles Spurgeon, Samuel P. Jones, Joseph Parker, and T. DeWitt Talmage of the nineteenth century. The early twentieth century gave us Andrew Murray, Ole Hallesby, P.T. Forsyth, and Oswald Chambers, whose writings are hard to surpass. Amy Carmichael’s poetry and prose written in India, have blessed millions of readers. More contemporary are the writings of C.S. Lewis and A.W. Tozer, which carry seeds of greatness.

The passage above comes from the book’s chapter on “Reading.” If you would like to see more, the entire book (although published as recently as 1992) is legally available for your review online.

“Shut up he explained” may not be proper English, but literature doesn’t need to be proper to be entertaining. And even though Lardner is no longer a familiar name, perhaps his writings are worth visiting.

For the moment, knowing the context of this delightful phrase makes the words all the more entertaining to me. After all, like many others, my dad often “explained” the same thing to me!

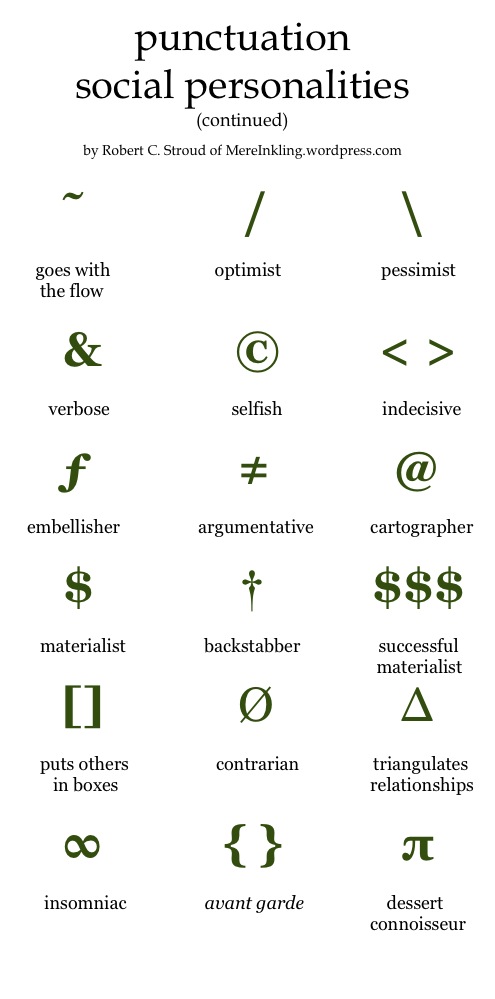

![]() Emoticons. Some people love them. Others find them irritating. I’m in the latter camp. That’s why I enjoyed a comic in the paper this week.* A fifty-something husband and wife are talking as she’s typing on her desktop.

Emoticons. Some people love them. Others find them irritating. I’m in the latter camp. That’s why I enjoyed a comic in the paper this week.* A fifty-something husband and wife are talking as she’s typing on her desktop.