Consider how one humble Anglo-Saxon poet can teach us about the ancient transition from the oral to written delivery of poetry.

Consider how one humble Anglo-Saxon poet can teach us about the ancient transition from the oral to written delivery of poetry.

In recent study about the transition from aural to literary communication I came upon the following fascinating fact.

In an essay entitled “Oral to Written,” J.B. Bessinger writes:

As literate authors learned to assimilate oral materials to pen-and-parchment composition, and since cultural life and centres of writing were controlled so largely by the Church, it was inevitable that the oral transmission of pagan verse would die out, or at best leave few records of an increasingly precarious existence. Meanwhile the invasion of bookish culture into an oral tradition proceeded.

Amid the overwhelming anonymity of the period, Cynewulf was the only poet who troubled to record his name, not from motives of a new literary vanity, but against the Day of Judgement:* “I beg every man of human kind who recites this poem to remember my name and pray . . .”

I’ve read elsewhere that the names of a dozen Anglo-Saxon poets were recorded, although only four have any work that has survived. I understand, however, why Cynewulf is so well recognized—several thousand lines of his poetry are extant. You can access copies of his work for free at Project Gutenberg and Internet Archive.

Curiously, we know no details about Cynewulf other than his name. This he included in his manuscripts, spelled in runic characters.

Cynewulf’s poetry was familiar to the Inklings.

In his diary during the 1920s, C.S. Lewis describes reading Cynewulf and Cyneheard while he bemoaned that Old English Riddles continued to represent an obstacle to him.

I set to on my O.E. Riddles: did not progress very quickly but solved a problem which has been holding me up. [Henry] Sweet is certainly an infuriating author . . .

[Following afternoon tea, Lewis] retired to the drawing room and had a go at the Riddles. I learned a good deal, but found them too hard for me at present.

J.R.R. Tolkien paid an unimaginable tribute to Cynewulf. He attributed to the ancient poet no less than the original inspiration for his mythopoeic conscience.

In the summer of 1913 Tolkien . . . switched course to the English School after getting an “alpha” in comparative philology. At this time he read the great eighth-century alliterative poem Christ, by Cynewulf and others.

Many years later from the poem he cited Eala Earendel engla beorhtost (“Behold Earendel brightest of angels”) from Christ as “rapturous words from which ultimately sprang the whole of my mythology.”**

Cynewulf was an inspired poet. And, it is possible to discern some Anglo-Saxon words which have made it into contemporary English when passages are lined up, side by side.

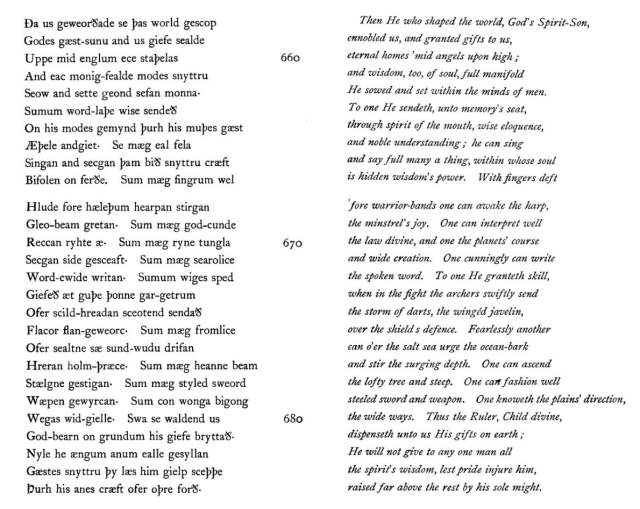

We’ll close now with a passage from his poem, Christ. These words come from the beginning of Part II (Ascension) and comprise the beginning of chapter four. For those who would like to compare the texts, a parallel version follows.*** (Just click on the image to enlarge it.)

Enjoy Cynewulf’s celebration of God’s abundant gifts, extended to poets, musicians, and all others.

Then He who shaped the world, God’s Spirit-Son,

ennobled us, and granted gifts to us,

eternal homes ’mid angels upon high;

and wisdom, too, of soul, full manifold

He sowed and set within the minds of men.

To one He sendeth, unto memory’s seat,

through spirit of the mouth, wise eloquence,

and noble understanding; he can sing

and say full many a thing, within whose soul

is hidden wisdom’s power. With fingers deft

’fore warrior-bands one can awake the harp,

the minstrel’s joy. One can interpret well

the law divine, and one the planets’ course

and wide creation. One cunningly can write

the spoken word. To one He granteth skill,

when in the fight the archers swiftly send

the storm of darts, the wingéd javelin,

over the shields defence. Fearlessly another

can o’er the salt sea urge the ocean-bark

and stir the surging depth. One can ascend

the lofty tree and steep. One can fashion well

steeled sword and weapon. One knoweth the plains’ direction,

the wide ways. Thus the Ruler, Child divine,

dispenseth unto us His gifts on earth;

He will not give to any one man all

the spirit’s wisdom, lest pride injure him,

raised far above the rest by his sole might.

_____

* Please don’t correct me regarding the misspelling of “judgment;” this quotation comes from a British text. ;)

** From Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship by Colin Duriez.

*** This image is derived from the 1892 translation of Cynewulf’s Christ by Israel Gollancz.

The lovely Anglo Saxon cross at the top of this page was discovered several years ago in the grave of a young teenage girl who had been buried near Cambridge.

I have blogged about Anglo Saxon legacy in the past . . . here and here.

My own type is ENTJ, which matches with King Théoden above. As I age, however, I am finding myself less extraverted and more desirous of solitude. That means I am progressively becoming an INTJ, and that aligns me with Elrond. Frankly, both of the characterizations suit me quite well.

My own type is ENTJ, which matches with King Théoden above. As I age, however, I am finding myself less extraverted and more desirous of solitude. That means I am progressively becoming an INTJ, and that aligns me with Elrond. Frankly, both of the characterizations suit me quite well.