Which is better for a person to write, fiction or nonfiction? That, of course, is an absurd question on its face. Every one recognizes nonfiction is best. (Just joking.)

Few of us are talented in the manner of C.S. Lewis — who excelled in both genres. Typically we have a knack for one or the other.

Which is best, becomes a question with a quite personal answer. And that response is determined by a number of interrelated elements. In which form are we more adept? Which do we prefer to read? For which are there greater avenues to experience publication? Through which do we receive more reward, extrinsic or intrinsic?

Christian writers consider another, hopefully overriding, factor. What type of writing does the Lord desire us to pursue? And, it should be noted that just like the daily Christian walk, this is a dynamic matter. It can change at any given moment, depending upon how the Holy Spirit leads. Once again, C.S. Lewis offers an ideal example of this truth. God may lead us to write something factual one afternoon, imaginative the next, and perhaps poetry on the succeeding morning.

What about the Prestige Factor?

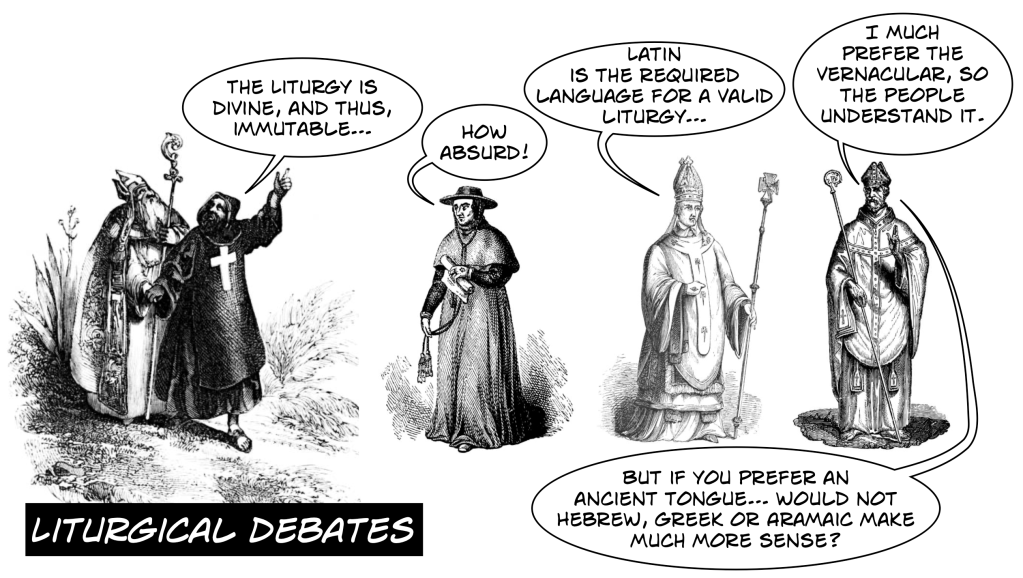

There is a subtle prejudice among writers, I fear. While it’s natural to think that the genre most challenging to one may require additional skill or discipline, it seems to me most writers tacitly accept the notion that fiction requires more talent.

While I personally disagree with that assessment, I understand it. After all, “facts” are readily available, and don’t rely on one’s imagination to devise. Still, good nonfiction is not inherently simpler to produce than quality fiction. (I mean, AI is proving every day that mediocrity can be reached in either genre in mere seconds.)

As an example of this subtle prejudice, see this (quite helpful) article by promising young historical fictionist Cheyenne van Langevelde.

In an insightful article entitled “Genre ~ What Christian Writers Should be Aware of,” she introduces the subject with the following observation:

As someone who hasn’t written nonfiction, I will not be discussing that branch of literature — though I’m sure it’s obvious how one could glorify God in their nonfiction writing. What I am going to talk about is the more challenging of the two branches: fiction.

I graduated from the University of Washington with an Editorial Journalism degree. While some argue Communication degrees are “worthless,” they may “set you up for life.” (That has certainly been my experience.)

Still, journalism doesn’t have the panache of “creative writing.” This, I suspect, is one reason that Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degrees exploded on the scene several decades ago.

When I open each issue of Poets & Writers, I’m overwhelmed by the number of ads for MFA programs, all over the globe. However, the October issue features a melancholy article titled “More MFA Programs Closing.” This is “despite all the value and prestige they bring to the university . . .”

The article cites “monetary pressures on universities and waning interest in the humanities” as major problems. Obvious to any non-MFA observer, the unbridled proliferation of MFA programs themselves might be the primary cause.

Combine with that the evidence that a younger generation is more concerned about their prospects of making a living, and one might anticipate a further winnowing of such programs.

For a balanced discussion of the subject, I commend “The MFA Degree: A Bad Decision?” — written by a writer who earned one, and subsequently “taught undergraduate and graduate courses in creative writing.”

I don’t believe MFA programs are inherently evil and have destroyed contemporary American literature. The majority of people teaching and taking creative writing classes are all trying to do good things. Nonetheless, I’ve begun to wonder if the MFA is, in fact, a bad decision.

It’s an interesting discussion, of value especially to those contemplating an MFA path. I leave that choice to the individual — as I leave to them the decision regarding whether to write fiction or nonfiction . . . or poetry, convincing historical fiction, satire, etc.

In order to expand their pool of prospective students, some MFA programs added “creative nonfiction” to their offerings. The focus of this genre is on training participants to consciously implement literary styles and techniques in order to make their factually accurate narratives more engaging.

While there is no doubt consciously taking these tools into consideration can improve the quality of many nonfiction works, it seems a bit exaggerated to label it “creative.” I would simply describe it as “good” or “well written” nonfiction.

For a description of how creative nonfiction can be implemented in memoirs and essays, you might enjoy an introduction to the subject from Writers.com. You may wish to follow that up with “The Five R’s of Creative Nonfiction.” (Mere Inkling applies at least four of them.)

C.S. Lewis offered an aspiring young writer some wonderful advice in 1959. “Write about what really interests you,” he suggested, “whether it is real things or imaginary things, and nothing else.” He added the parenthetical note that “if you are interested only in writing you will never be a writer, because you will have nothing to write about . . .”

Excellent advice for the young wordsmith. I would add that for the maturing scribe it is often productive (and even fun) to experiment with a variety of genres.

Who knows? Perhaps you will follow the Inkling tradition established by C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, being exceptional in fiction and nonfiction alike. Best of luck to those of you who embark on this journey!