Last week I wrote about “Learning Languages,” and I promised to follow up with a related theme – the creation of new words and languages. Let’s consider the simple matter first.

Adding New Words

Anyone can make up a new word. The problem is whether we have enough influence to have it adopted and used by another human being. (I add this qualifier to eliminate those who might attempt to skirt the question by simply training parrots to mimic the new word.) As Scientific American relates,

When parrots are kept as pets, they learn their calls from their adoptive human social partners. Part of their appeal as pets is their ability to sing lower notes than smaller birds and so better reproduce human voices.

So, while you may be able to trick one of your parrots into repeating a novel “word,” that doesn’t count for our purposes here.

Likewise, any other birds who mimic speech, including musk ducks and corvids (ravens, crows and their ilk). In fact, let’s exclude all nonhuman “speakers” from consideration. After all, AZ Animals introduces readers to seven specific animals of different species (only one of which is avian) whose “forebrain is . . . responsible for some animals’ ability to mimic speech.”

So, animals aside, who embraces and disseminates newly invented new words? Some words, of course, find a partially prepared or receptive audience because they are imported from other tongues. The global influence of English makes other languages especially vulnerable to its influence, which can be deeply resented. The “corruption” of mother tongues sometimes elicits reactionary responses – such as Italy’s current effort to purge English from the Italian Republic.

And some Italians are extremely serious about the task, proposing fines up to €100000. (That is not a typo; at today’s exchange rate it would be $109,857.50.) Their animus toward English follows the path established by the French, who frequently default to Napoléon’s order to refer to Britain as “perfidious Albion.” The Académie Française goes so far as to repudiate specific words, including business, cash, digital, vintage, label, and deadline.

Vocabulary adopted from other nation’s may be “new” to their most recent users, but such importation is certainly not the same as fabricating novel words from the proverbial “whole cloth.”

True Neologisms

I wrote a moment ago that creating words is easy, but persuading others to use them is quite another thing. I’ve discussed this subject in the past, in “Create a Word Today” and “Creative Definitions.” Sadly – and fittingly – none of my personal neologisms have caught on.

Popular creative writers may, however, find their fancies adopted by larger audiences. Shakespeare’s “bedazzled” was birthed in The Taming of the Shrew. The “chortle” was first heard in Lewis Carol’s “Jabberwocky.” “Pandemonium” was revealed as the capital of Hell in Milton’s Paradise Lost. And the first “Nerd” was encountered in Dr. Seuss’ If I Ran the Zoo.

Some neologists were particularly prolific. How about these few additional examples from the Bard:

Bandit ~ Henry VI

Dauntless ~ Henry VI

Lackluster ~ As You Like It

Dwindle ~ Henry IV

Oh, and Grammarly adds, “Shakespeare must have loved the prefix un- because he created or gave new meaning to more than 300 words that begin with it.” Can you imagine a world without:

Unaware ~ Venus & Adonis

Uncomfortable ~ Romeo & Juliet

Undress ~ Taming of the Shrew

Unearthly ~ The Winter’s Tale

Unreal ~ Macbeth

Before moving on, it would be fair to note that some voices consider this achievement by Shakespeare to be “a common myth.”

It turns out that Shakespeare’s genius was not in coining new words – it was in hearing new words and writing them down before they became widespread, and in wringing new meaning out of old, worn-out words: turning “elbow” into a verb and “where” into a noun. He didn’t invent the words, but he knew how to use them better than anyone.

C.S. Lewis was not a philologist, but he did create a few novel words. The Inkling scholar who pens A Pilgrim in Narnia has written on this subject here and here.

J.R.R. Tolkien was no slouch at inventing English words himself. Some which now reside in our common vocabulary include hobbit and orc. The latter he derived from an Old English word, orcþyrs, a devouring monster associated with Hell. More surprisingly, Tolkien created the modern word “tween,” albeit in the context of hobbits, who lived longer lives than we.

At that time Frodo was still in his tweens, as the hobbits called the irresponsible twenties between childhood and coming of age at thirty-three.

Envisioning novel words is relatively simple, but inventing an entire language, is an infinitely more complex challenge. The universally acknowledged master is J.R.R. Tolkien, whose Elvish tongue has become a “living” language.* But he was not alone in building internally consistent linguistic systems. Albeit, no philologist came near to Tolkien’s expertise, which included elaborate etymologies.

Before considering Tolkien himself, we will note several other efforts of a similar kind. And, following a discussion of Tolkien, we will conclude with a note about his good friend, C.S. Lewis. For, despite the fact that Lewis was not a philologist himself, it is interesting to note that he too dabbled in creatio linguarum.

Inventing New Languages

Some “constructed languages” are formed with practical purposes. Esperanto, birthed in 1887, incorporated elements from existing languages and was envisioned as a common “international auxiliary language.” It boasts its own flag, and claims to be the native language of approximately a thousand people.

One curious use of Esperanto came in its adoption by the United States Army as the “Aggressor Language” used in twentieth century wargames. The curious can download a copy of the now-rescinded Field Manual 30-101-1, which provided guidance for its usage “which will enhance intelligence play and add realism to field exercises.”

Another genuine constructed language is Interlingua. Developed between 1937 and 1951, it is based primarily on the shared (and simplified) grammar and vocabulary of Western European languages.

In addition to languages constructed for international use, there are a variety of tongues created for fictional applications. “To learn Klingon or Esperanto” describes how linguistic anthropologist Christine Schreyer “invented several languages for the movie industry: the Kryptonian language for ‘Man of Steel,’ Eltarian for ‘Power Rangers,’ Beama (Cro-Magnon) for “Alpha” and Atlantean for ‘Zack Snyder’s Justice League.’” While none of these could ever rival the languages of Middle Earth, her bona fide linguistic credentials place her in a context similar to J.R.R. Tolkien. The interview reveals how Schreyer balances her creative impulses with her anthropological concerns.

I teach a course on linguistic anthropology, in which I give my students the task of creating new languages as they learn about the parts of languages. Around the time I started doing that, “Avatar” came out. The Na’vi language from that movie was very popular at the time and had made its way into many news stories about people learning the language – and doing it quickly.

My other academic research is on language revitalization, with indigenous or minority communities. One of the challenges we have is it takes people a long time to learn a language. I was interested to know what endangered-language communities could learn from these created-language fan communities, to learn languages faster.

Other fictional languages that exist include R’lyehian (from Lovecraft’s nightmare cosmos), Lapine (from Watership Down), Fremen, the Arabic/alien blending (from Dune), Parseltongue (ala Harry Potter), Dothraki (from Game of Thrones), Ewokese, etc. (from Star Wars), Goa’uld and others (from Stargate), Minbari and more (from Babylon 5), and the gutturally combative Klingon and others (from Star Trek). This brief list is far from exhaustive.

Tolkien, Lewis & New Languages

The languages forged by J.R.R. Tolkien are unrivaled by any conceivable measure one might employ. They are no mere stage dressing, like some of the aforementioned examples. Even those with developed vocabularies and consistent grammar fall far short of Tolkien’s creation. In terms of the histories of his languages, his diligent etymologies beggar all other such efforts. Of course, for Tolkien this was no competition. He was driven to make his languages as flawless – not “perfect,” but realistic – as humanly possible. It was a linchpin in his subcreative labor.

As a skilled calligrapher, Tolkien devised unique alphabets to complement his languages. The letters in his alphabets were not devised as mere adornments. Tolkien left that to lesser imaginations. Nor were his scripts restricted to Tolkien’s fiction. The Tolkien Estate offers an insightful essay on “Writing Systems.”

Tolkien also used invented scripts that were not associated with any of his fictional worlds. An early example is the Privata Kodo Skauta (Private Scout Code), which appears in a still unpublished notebook from 1909 called the Book of the Foxrook. This makes use of a phonetic code-alphabet, as well as a number of ideographic symbols representing full words. . . .

Toward the end of his life, Tolkien made use of the New English Alphabet, a phonetic script that combined the logical structural principles of the Angerthas and the Tengwar with letters that looked more like Greek or Latin. The alphabet has not yet been published in full, but examples can be seen in . . . J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator.

The footnote below links to some resources for those who would like to learn how to speak the languages of the elves. By way of help with pronunciations, remember the following advice:

Use an Italian accent to pull off Quenya speech patterns. In general, you can kind of sound Elvish – even without following the rules of the language – by applying an Italian accent when pronouncing Quenyan words. Native Italian speakers tend to use speech patterns from their native tongues to interpret English words, which can make your Elvish sound practiced even when it isn’t.

Speak with an Irish or Scottish accent to pull off a natural Sindarin accent. Irish and Scottish speakers tend to speak English by emphasizing sounds in the front of a word regardless of the standard pronunciation. This is a pretty good method for pronouncing Sindarin words, since the vast majority of them stress the first syllable.

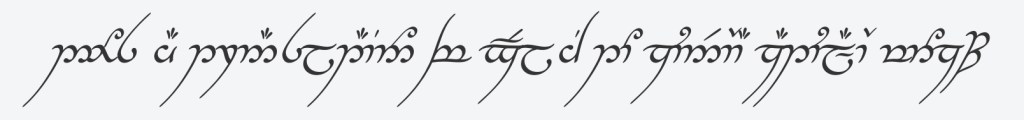

For those who want to quickly capture some Elvish script without the effort of studying, consider the English to Elvish online translator, which is offered by the company that fashioned The One Ring for Peter Jackson’s cinematic epics. I decided to test the translation tool and posed the question: “Does AI translation of English to Quenya actually work?” The software swiftly complied.

It looks elegantly correct, but unfortunately, I’m unable to personally verify its accuracy. And I must confess to modest trepidation since the site advises:

“USE CAUTION BEFORE COMMITTING TO ANY TATTOOS, INSCRIPTIONS AND ENGRAVINGS” [triple emphasis in original].

The Jens Hansen site sells jewelry, as befits the fasioners of The One Ring. In addition to hosting the translator, they offer a free pdf document called Elvish 101 in 5 Minutes. It’s an interesting document, but it reveals a limitation I assume is shared by the online generator. It is a resource for transliterating, not translating, words. Not quite the same thing . . . but the script still looks elegant.

Tolkien was the master of creating languages for his subcreation, but C.S. Lewis also used the same technique in the writing of his Space Trilogy. Each work focuses on an individual planet in our solar system, which is referred to in the books as the Field of Arbol.

While a number of languages have developed over time, the original language, known as Old Solar, is retained by some, and learned by the series’ protagonist Dr. Elwin Ransom. Ransom is a philologist at Cambridge, and as he is modeled after Tolkien, it’s no surprise his first name means “elf friend.”

In Perelandra, Ransom describes how a language he learned on Mars was once shared by all.

“It appears we were quite mistaken in thinking Hressa-Hlab the peculiar speech of Mars. It is really what may be called Old Solar, Hlab-Eribol-ef-Cordi. . . . there was originally a common speech for all rational creatures inhabiting the planets of our system: those that were ever inhabited, I mean – what the eldila (angels) call the Low Worlds. . . .

That original speech was lost on Thulcandra, our own world, when our whole tragedy [the Fall] took place. No human language now known in the world is descended from it.”

Lewis’ use of Old Solar is sparing, but a partial lexicon can be found at FrathWiki. There, for example, you will learn that “honodraskrud” is Old Solar for a “Groundweed; an edible pinkish-white kind of weed, found all over the handramit” of Malacandra (Mars).

The accomplishments of Tolkien and Lewis are difficult to compare. These two brilliant scholars shared a great many interests, but wrote with far different goals. We rightfully expect genius to vary between such individuals. This is well illustrated by their differing treatments of constructed languages, as Martha Sammons describes so well in War of the Fantasy Worlds.

Tolkien began with invented languages and then developed an elaborate mythology to create a world where his languages could exist. Lewis’s works began with mental pictures; he would then find the appropriate ‘‘form’’ to tie together the images. . . .

[Tolkien’s] penchant for historical and linguistic detail is unparalleled. In contrast . . . Lewis uses just enough language, geography, and science to make his novels believable.

While either approach may inspire those among us who aspire to writing, we best avoid attempting to emulate either author. Best, I believe, to compose our epics with the language that most naturally flows from our pen.

* While some fans of Klingon and Na’vi may learn to speak in those tongues, the students of the languages of Arda, typically possess greater ardor for the languages of Middle Earth. For example, an online guide to learning Elven languages begins by answering the question, “why study Elvish?” And a free online course for learning Quenya is offered here. Among the Quenya dictionaries, the finest free example is available at Quenya-English Dictionary English-Quenya Dictionary.