Several unique items are buried with modern popes when they die. Most, including their vestments, point to their spiritual role as the Bishop of Rome and patriarch of the Roman Catholic Church. One, however, highlights his secular role as the leader of the world’s smallest independent nation state.

This post is not about Pope Francis’ reign, or the papacy in general. As C.S. Lewis noted in a letter to an American poet, Mary Willis Shelburne, opinions on such matters differ in sometimes unproductive ways. In response to a comment she had written about the passing of Pope John XXIII (1881 – 1963), who had convened the Second Vatican Council, Lewis astutely observed,

God’s purposes are terribly obscure. I am thinking both of your [physical] sufferings and of the removal of such a Pope at such a moment. And the horrid conclusions which some bigots on both sides will probably draw from it.

Rather than discussing the role of the Bishop of Rome, I am considering one specific aspect of the office of the Bishop of Rome – the formalities associated with the funeral and burial/interment of a deceased pope. My focus is further restricted to a single unique facet of that process. This involves the coinage of the Vatican City State issued during their reign.

Despite its status as a nation, Vatican City has declined full membership in the United Nations. This is due to the admirable goal of remaining detached from the official political tentacles associated with having an official vote. Instead, through the Holy See, the papacy’s ecclesiastical office, the Roman Catholic Church maintains a presence and voice in the UN.

Vatican City is one of the few independent states that has not become a member of the United Nations. It does hold permanent observer status, with all the rights of a full member except for having a vote in the General Assembly.

On April 6, 1964, the Holy See became a Permanent Observer Mission to the United Nations and established its Mission in New York City. This was fitting, not only because of the growing involvement of the Holy See in UN deliberations, but above all because the four pillars of the UN as enshrined in its Charter dovetail very well with four main pillars of Catholic Social Teaching . . .

The Holy See enjoys by its own choice the status of Permanent Observer at the United Nations, rather than of a full Member. This is due primarily to the desire of the Holy See to maintain absolute neutrality in specific political problems.

In accordance with tradition, “preparations are also being made for a numismatic commemoration of the Sede Vacante.” The Latin term means “vacant seat,” and refers to the transitional period between popes. Thus, in addition to the papal coins minted for each pope, special issues are normally released during the interims. However, due to a reorganization of the Vatican’s coinage office, CoinsWeekly reports it remains “uncertain whether a 2-euro commemorative coin” will be produced for this papal interregnum.

NumismaticNews echoes the fact that due to their rarity, Sede Vacante issues rapidly increase in value. Fortunately due to their infrequency, they “ are seldom at the center of a collector’s radar. That’s probably a good thing, as it means we are not losing popes quickly or routinely.”

A number of items are traditionally included in a pope’s casket. Unsurprisingly, these include a miter, crozier, and rosary. They also include coins minted during their reign, reflecting their role as ruler of the Papal State. This last fact surprised me.

So, precisely what is the precedent being set with Pope Francis’ funeral? First, he was not buried in the Vatican, but in a basilica dedicated to St. Mary.

There was another, more significant symbol of the simplicity that characterized his papacy. While popes traditionally have three elaborate caskets nestled inside one another, Francis asked to have only one simple wooden casket with a modest zinc inner lid.

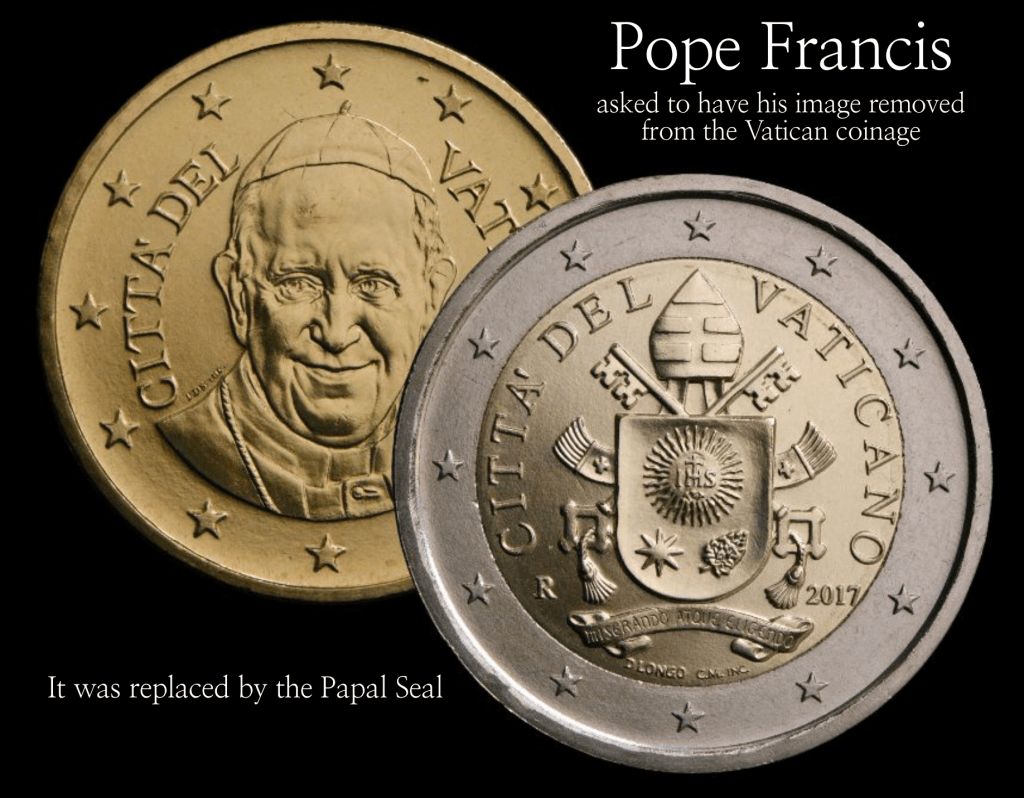

Pope Francis’ 2017 Revision of Vatican Coinage

For centuries, the portrait of the current Bishop of Rome graced coins in Rome. That tradition ended with Pope Francis. In 2017, he personally requested that his visage no longer appear on coins. This is commendable, since it was presumably based on Francis’ humility.

This then, his image has been replaced by the papal coat of arms. Notably, every other country minting euros bears the head of its head of state. It will be interesting to see whether or not Francis’ successor follows his example.

A Brief Note on Protestant Coinage

Although there have been some historical attempts to create governmental structures led by religious leaders besides Roman Catholicism, they have been the rare exception. (The claimed leadership of the Church by sovereigns such as King Henry VIII is another case.)

In Zurich, Huldrych Zwingli (1484 – 1531) sought to establish a theocracy, and actually perished on the battlefield resisting the Roman Catholic armies of several Swiss cantons. John Calvin (1509 – 1564) pursued similar goals in Geneva, and beyond. Calvin, however, never bore arms in his effort.

Fortunately, the “two kingdoms” theology of Martin Luther became dominant in primarily Protestant realms. It is based on the declaration Jesus made during his trial before Pontius Pilate that “My kingdom is not of this world” (John 19).

For a fascinating discussion of the implications of this theological position, consider “Martin Luther’s Farewell to Arms: The Two Kingdoms and the Rejection of Crusading.”

Turning to numismatics, it is not rare to find religious leaders portrayed on historical coinage. However, these portrayals serve as commemorations of individuals who have made a cultural or ethical contribution to a particular society – not because they sat upon a throne.

For example, Switzerland minted a 20 franc coin with the images of Zwingli and Calvin during the 500th anniversary of the Reformation.

Likewise, in 1965, the Communist government of Czechoslovakia produced a 10 korun coin in honor of the 550th anniversary of the martyrdom of Jan Hus. This particular coin, like many similar pieces, was actually minted as a non-circulating coin, intended for collectors rather than daily commerce.

This leads us to note that most coin-like pieces of metal bearing the likeness of reformers are actually medallions, not coins. As such, the vast majority of the commemoratives have been fashioned by organizations, rather than governments.

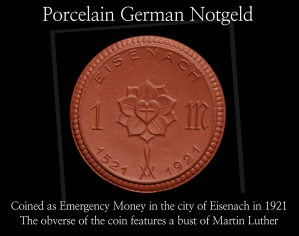

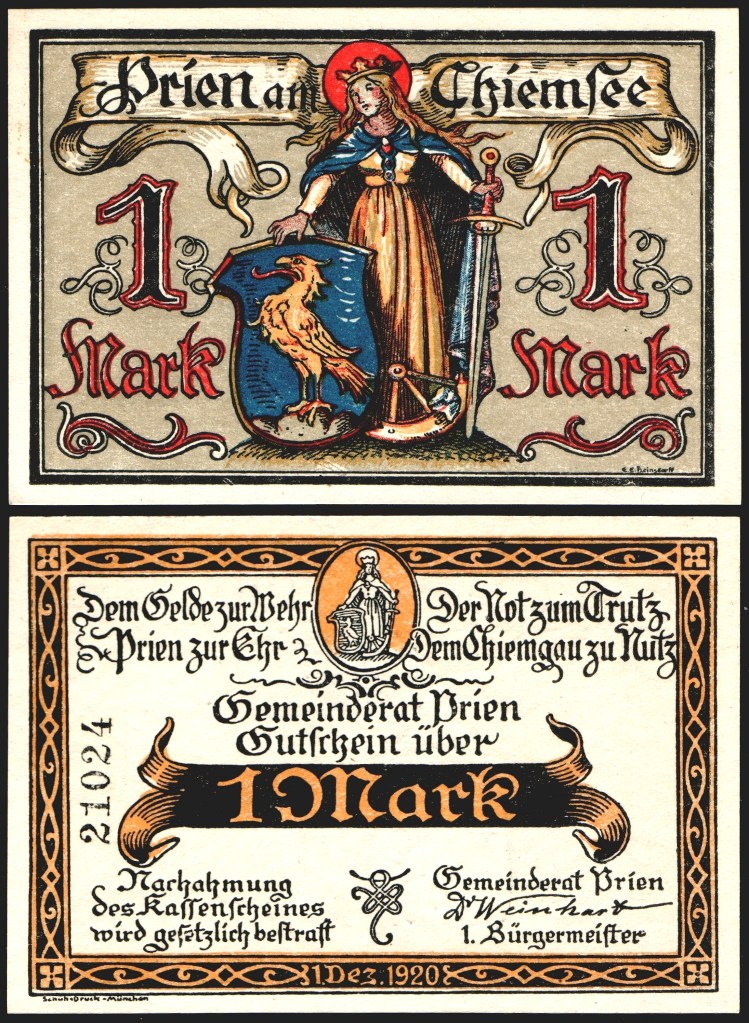

Being an amateur numismatist and a Lutheran pastor myself, I have several related items in my personal collection (none of which were costly, of course . . . since it’s just a hobby). One of my favorite items is a genuine 1 Mark coin minted in Eisenach in Weimar Germany in 1921 (pictured below). What makes it especially unusual is that due to postwar metal shortages, it was actually struck in porcelain!

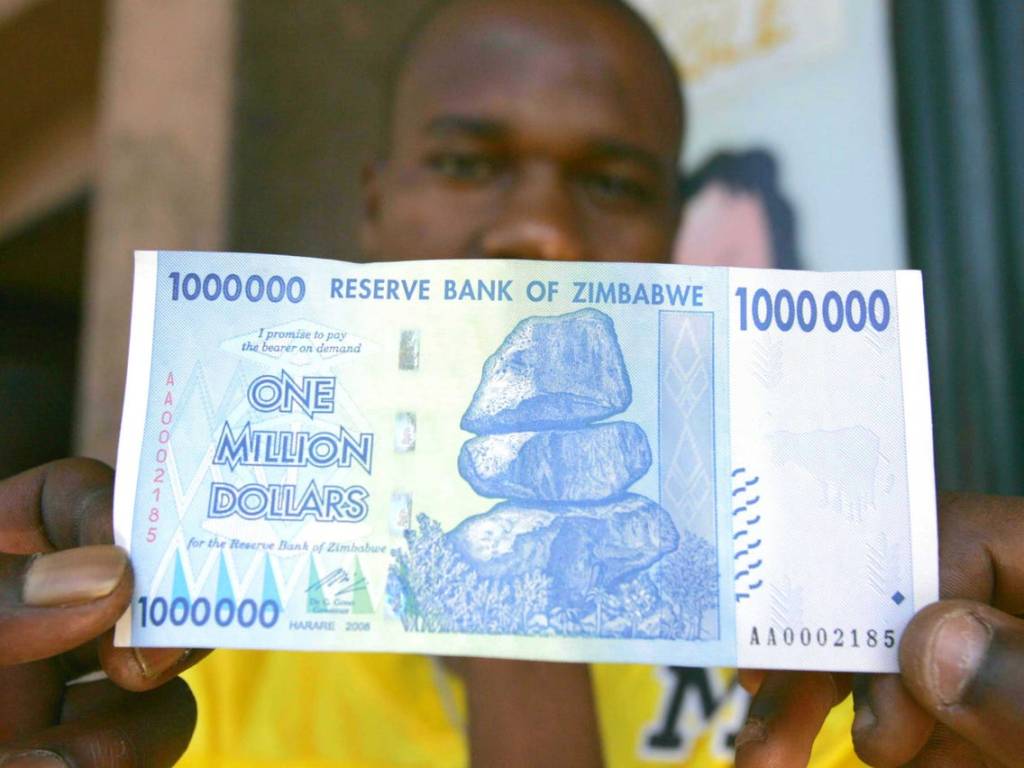

This emergency coinage and currency was called “Notgeld,” which means “necessity money” because individual cities found it necessary to provide their own money when the Reichsbank succumbed to hyperinflation between the world wars.

The city of Eisenach chose the centennial of Martin Luther’s work because of his historic ties to the city. The Lutherhaus Eisenach cultural center commemorates, among other events, Luther’s early schooldays there, and his stay at Wartburg Castle where he translated the New Testament into German.

Conclusion

In light of Pope Francis’ funeral and the association it has with numismatics, it is a good time to consider how coinage has often carried a religious message. Although this was more frequent in past centuries, it still occurs today. It will be interesting to see just how many nations eventually mint coins in honor of Pope Francis. The Philippines, Samoa and the Cook Islands already have.

And even Narnia, the home of Aslan, minted coins in honor of its heroes, didn’t it?