Reading is not only one of life’s pleasures, the content and ethos of what we read, subtly influences the shape of our very lives.

C.S. Lewis loved books with genuine passion. While many people only perceive books as compilations of information or as sources of fleeting entertainment, he knew them as far more. Only someone sharing Lewis’ affection and wisdom will identify with the following passage from his essay “An Experiment in Criticism.”

The man who is contented to be only himself, and therefore less a self, is in prison. My own eyes are not enough for me, I will see through those of others. Reality, even seen through the eyes of many, is not enough. I will see what others have invented. . . .

Literary experience heals the wound, without undermining the privilege, of individuality. There are mass emotions which heal the wound; but they destroy the privilege. In them our separate selves are pooled and we sink back into sub-individuality.

But in reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like the night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do.

Lewis scholar and emeritus professor of English, Dale J. Nelson, has been providing a wonderful service in recent years as he explores the books which found a place in C.S. Lewis’ personal library. “Jack and the Bookshelf” is a continuing series which appears in CSL, journal of the New York C.S. Lewis Society. Founded in 1969, the organization “is the oldest society for the appreciation and discussion of C.S. Lewis in the world.”

Nelson’s task of editorially archiving C.S. Lewis’ library is complemented by the work of our mutual friend, Dr. Brenton Dickieson. In a “comment” praising Dickieson’s compilation of “C.S. Lewis’ Teenage Bookshelf,” Nelson offers a commendation with which I fully concur.

Thank you for assembling that list of books . . . I’d encourage Lewis’s admirers to take their appreciation of CSL to the next step and delve into the things he liked to read throughout his life.

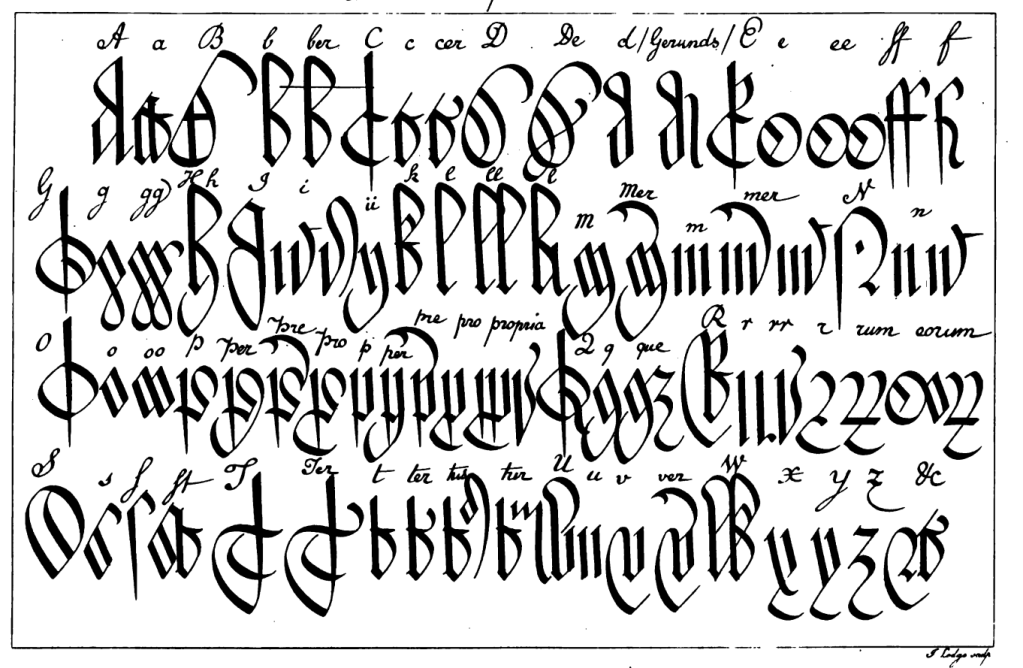

Nelson’s contribution to the December 2023 issue is the fifty-ninth in his series, and discusses a fantasy work titled The Worm Ouroboros by E.R. Eddison. Eddison (1882-1945) was a Norse scholar, and his fascination with mountains combined with that, to resonate with Lewis’ passion for northernness.

Dr. Nelson, who has added an array of science fiction to his own academic work, possesses superb credentials for exploring the connection between Lewis and Eddison.

Nelson relates that, at C.S. Lewis’ invitation, Eddison attended two gatherings of the Inklings. At the second, Eddison – who relished critiques of his works in progress, as do many serious writers – read from a project which would not be published due to his death the following year.

Eddison’s themes more closely resembled J.R.R. Tolkien’s than Lewis’ own. In Nelson’s words, both “Tolkien and Eddison wrote masterpieces of heroic fantasy whose values differed markedly.”

Another distinction is that while Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings has maintained its mythic rigor, Eddison’s oeuvre feels rather anchored to the formative years of the genre, prior to the so-called Golden Age of science fiction (and fantasy).

If you would like to read this book, which was enjoyed by both Lewis and Tolkien, you can download a copy of it at Internet Archive. If you enjoy dwarves, goblins, manticores and hippogriffs, you are unlikely to be disappointed.