Translating literature from one language to another is a valuable, yet often undervalued, skill. It breaks the linguistic shackles restricting the benefits of good books to those literate in the language in which they are composed.

You can think of it this way. Without the dedicated efforts of translators, someone familiar only with English – e.g. as is, sadly, the case with most Americans – could never read the works of ancient Greeks or Romans. Asian philosophy such as the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism would be virtually unknown in the West.

Even contemporary literature from most of the world would be beyond our access. And, obviously, God’s written Word would only be accessible to those who mastered Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

While C.S. Lewis is seldom thought of as a translator, it was indeed one of his talents. That doesn’t mean he devoted serious energy to translation. That was not his vocation. On the contrary, in 1945 he wrote: “People praise me as a ‘translator,’ but what I want is to be the founder of a school of ‘translation.’” (I discussed this a number of years ago in “C.S. Lewis’ School of Translation.”)

Dedicated translators have played an invaluable role throughout recorded history. A number of people still make translation their life’s labor. Yet, there are dark clouds on their horizon.

Is there a Future for Translation by Human Beings?

A recent literary journal alerted me to advances in artificial intelligence, which now jeopardize the future of professional translators.

Back in 2023, an article in Forbes compared the respective advantages and challenges of the two methods. They accurately identified one distinction between a truly fluent human and an artificial substitute.

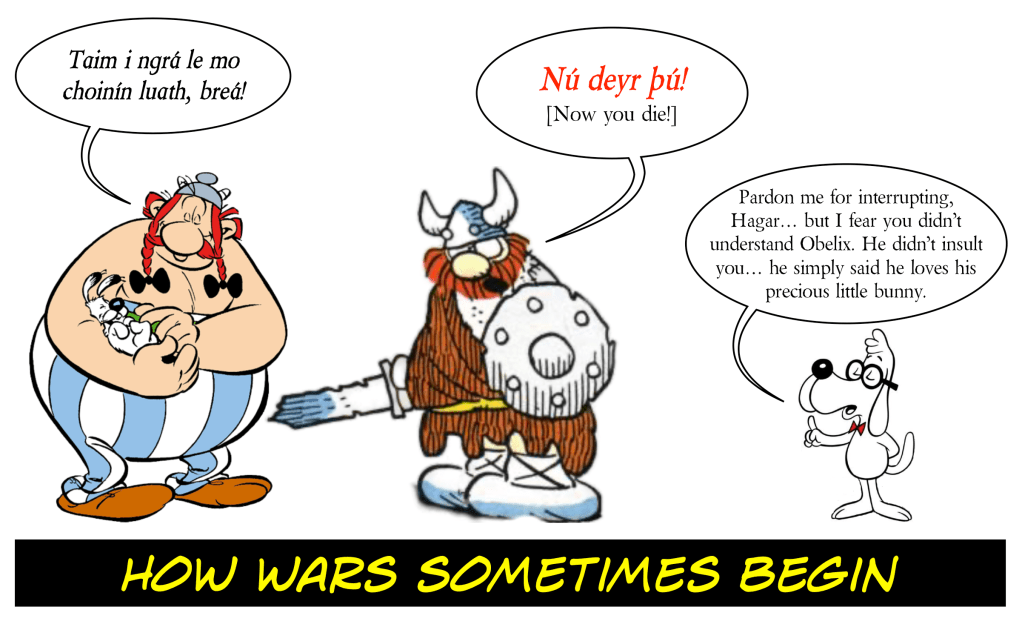

Language is complex, and culturally specific expressions such as idioms and metaphors, as well as ambiguous or ungrammatical sentences and other context-dependent word choices, can be challenging for AI algorithms.

Unsurprisingly, that same year the American Translators Association offered a more critical opinion in “Machine Translation vs. Human Translation: Will Artificial Intelligence Replace the World’s Second Oldest Profession?”

We already mentioned that computers don’t possess our human capacity to comprehend meaning. The creative process, especially when it comes to translation, is the pinnacle of meaning. Human translators translate meaning, not words. The art of translation is understanding the meaning of the original text and then transforming it into something that communicates the same message (or evokes the intended emotion) but might not superficially look like an exact equivalent. . . .

But both now and then, professional translators are here to stay. Equipped with unique human skill and a toolbox full of tech, they’re ready to continue helping the world navigate the tricky business of multilingual communication – transporting messages appropriately, creatively, consistently, and securely to whatever audience you aim to reach.

In short: machine translation can help when it doesn’t count, but professional human translation is there for you when it does.

Related to expressly literary translations, in contrast to mundane subject matter, the current issue of Poets & Writers contains a piece titled “AI Threatens Literary Translation.” When a European subsidiary of Simon & Schuster announced they would begin limited use of AI for this purpose,

Reactions rose in a flurry: Writers, publishers, and translators contended that AI would produce “bland” work. They lamented the possibility of lost jobs. The European Council of Literary Translators’ Associations resisted the standardization of an idiosyncratic process, stating that the imagination, understanding, and creativity that translation demands are “intrinsically human.”

This informative essay acknowledges that “AI isn’t new to translation either. Literary translators sometimes input segments of their source text into AI-based technologies . . . to generate ideas for particularly thorny passages. But these tools have to be used ‘very carefully . . . because the translations it produces are error-ridden and devoid of flow or beauty.’”

A Quick Experiment with AI Translation

Before completing this post I took a brief (less than ten minute) excursion to ChatGPT to experiment with their translation tool.

The results appear below (all produced in a mere handful of minutes). First I asked the AI to compose a sonnet on the subject of translation. Then I requested translations of that sonnet in five different languages. I have included the sonnet and the final two lines of each translation below.

You can perform a more elaborate experiment yourself, especially if you are familiar with more than one language. This would enable you to compare the accuracy of the translation. Or, perhaps one might take a translated version and translate that back into the original language, to see how closely it relates to the starting point.

In my experiment, the AI was constrained by needing to maintain the original’s form as a sonnet. I assume that if it were simply a literal translation, it may have modified the vocabulary and grammar. Each translation included footnotes. To illustrate how elaborate some of these notes were, I’ve reproduced those which appeared with the translation into Aramaic.

Frankly, if this is what these early AI prototypes are capable of, it appears to me that professional translators may truly have something to be worried about.

The Sonnet

In languages vast, where meanings hide and shift,

A translator’s art gives voice to what is known.

Through words, they bridge the gap, a timely gift,

To carry thought from one to others’ throne.

The rhythm, tone, and essence all must stay,

Though words may bend, they still must hold their grace.

A careful hand must guide the text’s relay,

To keep its heart while moving through time and space.

Yet oft the meaning’s lost in fleeting sound,

Or tangled in the strings of foreign speech.

But still they strive, where words and thoughts are bound,

To bring the message close, within our reach.

A translation’s not just words that blend –

It’s worlds revealed, with meaning without end.

~ Latin ~

Translatio non est solum verba iuncta –

Sed mundi patent, et mens non est puncta.

~ Old English ~

Nis anginn of wordum gemenged anum –

Ac worulda onwreah, and andgit ne swylt.

~ Classical Greek ~

Οὐ γάρ μόνον λέξεις αἱ μεταφράσεις,

ἀλλὰ κόσμοι φαίνονται, ἄνοια οὐδέποτε.

~ Middle Egyptian ~

𓏏𓂋 𓅓𓏏 𓊪 𓏏𓏤 𓆑𓏏 𓊵𓏤,

t r mt ḏbꜥ t ft ḏbꜥ

(“A translation’s not just words that blend –”)

𓂋 𓅓𓏏 𓆑𓏏 𓊵𓏤 𓏏𓏏𓀀.

r mt ft ḏbꜥ t t

(“It’s worlds revealed, with meaning without end.”)

~ Classical Aramaic ~

ܬܪܓܡܐ ܠܐ ܗܘܐ ܒܠܚܘܕ ܡܠܐ ܕܡܬܚܠܛܢ,

ܐܠܐ ܥܠܡܐ ܡܬܓܠܝܢ، ܘܡܕܡ ܠܐ ܚܒܠ.

Notes on the Translation:

1. Classical Aramaic Grammar & Style: The sentence structure follows Classical Aramaic syntax as used in ancient texts. Some phrases had to be adapted poetically since direct translations of modern concepts do not always exist.

2. Vocabulary Adjustments: “Translator” = ܡܬܪܓܡܢܐ (metargemana), a direct and historically accurate term. “Translation” is expressed as ܗܫܬܘܪܬܐ (hishtorta), meaning “interpretation, explanation.” “Essence” is translated as ܡܗܘܬܐ (mehutā), meaning “nature, essence.” “To bridge the gap” = ܡܫܬܪܝܢ ܓܦܐ (meshatrin gapé), literally meaning “to stretch wings” (a poetic expression).

3. Preserving the Poetic Flow: The rhythm and parallel structure of the original sonnet were carefully kept. Adjustments were made for metrical and phonetic balance in Aramaic.

4. This version captures the spiritual and poetic depth of the original while remaining faithful to the Classical Aramaic linguistic style.

5. Would you like an audio recording or a version in Syriac script for authenticity? Let me know how you’d like to refine it!

And all of this in ten minutes. Unfathomable . . .

I am fully aware of the difficult work of the translator and I do not know if Artificial Intelligence will be able to capture all the nuances in a text.

I am with you, Luisa. The jury remains out on the matter. In fact, like most things with aesthetic considerations, I would be shocked if there is ever consensus on the subject.

As you say, it is challenging to capture every nuance. And translators who capture some in a given work, will likely miss others. It seems to me that the best translator is actually the original author.

Of course, that limits the process to authors who are at least bilingual…

And such artists are quite rare — very few are as gifted in this regard as you are!

Thank you very much for these further reflections and for your praise. It touched my heart❣️

Rob,

If we don’t allow machines to take our creativity and language skills we will out perform AIs.

Thank you, Gary

Gary Avants Forbear Productions * *garyavants66@gmail.com garyavants66@gmail.com

Well, Gary, I’m afraid we’ve lost that battle. There will always be people focused on material gain… and if there is something to be had in the short term, that kind of individual will utterly ignore any longterm implications.

My ten minute experiment stunned me, since my last look at the ChatGPT found the program far more primitive. I can only imagine how advanced it will be a year from now.

The key to resolving this challenge is to develop hybrid translation tools that combine human creativity and AI precision while enhancing the translator’s role as an editor to ensure quality.

gtu

I agree that your solution to this dilemma is the only logical one. A synergistic approach…

I agree that Chat GPT is improving. The rhyme scheme and throughline are there, but the words are uninspired. Inspiration, it seems to me, requires more than just regurgitated and recombined ideas, it requires a heart.

True. Inspiration is a precious gift humanity experiences as a gift from God.

But when it comes to evaluating things like poetry, art, or similar expressions, it becomes fairly subjective. For example, the sonnet above is far more pleasing to me than many examples composed by actual human beings.

The true essence of inspiration may be lacking… but the end result may be more satisfying.

The ability to distinguish between the production of humans and machines may be growing more challenging each day.

The puzzle at the root of this post first became known to me in the late 1980s when I was working for a machine translation company. In other words, German documant in, and French one out. The ‘AI’ of that era consisted of an actual body of a couple of thousand rules applied according to various weighted decisions. Today’s AI works differently, digesting massive amounts of real-world language snippets and finding statistically likely correspondances between two languages. Of course this would be very limited with ancient Aramaic, since the scale of snippets available there is much much lower.

What I came to see is that a truly skillful translator must not only know a foreign language but also have digested the foreign culture. Almost impossible. Thinking and thoughts live in a higher space of meaning than do language and words. When we express thinking in words we only hint at what is being thought. We must use our own thinking, as listener, to rebuild the possible thought structures behind what the speaker reduced in his words. This happens so quickly that we do not notice it usually. (This is connected with the mystery of the Word in John;s gospel but no space for that here.) What AIs do is threaten to foul the experience of the living Word in our conversations. The invite us to believe that the written words equal all of the meaning and that living thinking is not of any consequence. It is a very very subtle evil.

“Thinking and thoughts live in a higher space of meaning than do language and words.”

This is a truly profound fact that few people comprehend.

Thank you for your insights, including your personal background with machine translation in the past. I don’t recall reading any articles exploring that history in depth… but the contrast you draw between the early process and what we see today has definitely piqued my interest.

Well, there is the old tale from the beginning days of machine translation. It was a dream of the earliest computer researchers to translate documents. They all believed it would ne easy. It was not. What Google does now is locate the statistically likely correlates in language X from language Y text snippets. (I am over-simplifying here :)

When the first efforts to computationally translate the English sentence: “The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.” into Russian and then use the same technique upon that result to translate it back into English… the result was: “The liquor is strong but the meat is rotten.” This gives a hilarious idea about how important context is in understanding language. And that context is more than just textual. There is also vocal inflection and eye gestures, phrasing, etc. A million subtle things. GPTs “know” nothing about this.

Wonderful historical note, and entertaining example of the limitations of GPTs.

I suppose that some of the visual cues you cited may already be part of the AI agenda. I can see how they might be amassing data right now on different accents, inflections and other audible clues…. plus similar information based on the visual cues.

Yes, GPTs have much still to “learn.”