Sometimes we read for business. Other times we read for pleasure. Few people are so fortunate as to have these two purposes overlap.

When the goal is the former – the necessity of reading a particular document, our desire is usually to simply “get it done.” We want to arrive quickly at the point, so we can move on to some other project. In this context, digressions are definitely something to be avoided.

This is how military writers are taught to do their job. Deliver the goods immediately, with zero interest in the prose. (Well, apart from proper grammar and spelling.) This principle is frequently described with the acronym BLUF – bottom line up front. This approach makes sense, when lives can literally be on the line and the need to make sound decisions swiftly is urgent.

The Harvard Business Review puts it bluntly: “In the military, a poorly formatted email may be the difference between mission accomplished and mission failure.” Being the HBR, they naturally translate this concept for application in the business world.

If you are curious, you can freely download some of the military writing manuals available online. Warning: these manuals tend to include lots of tedious details that ironically appear to violate the BLUF principle itself!

Army Regulation 25–50 Preparing and Managing Correspondence

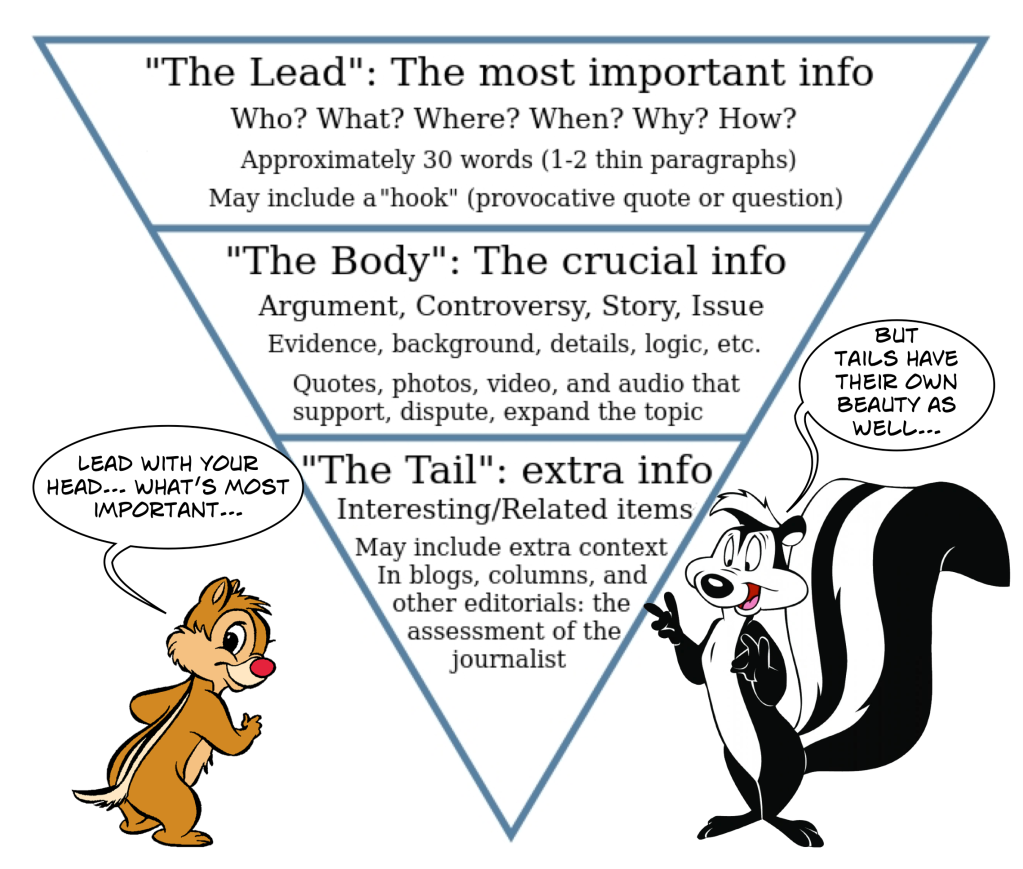

Similar to the military approach, we have the civilian version, which remains common in traditional journalism. (Even though printed newspapers continue to vanish, this approach is still found in many digital outlets.) This technique is referred to as the Inverted Pyramid Structure. Here is one concise definition:

The inverted pyramid is the model for news writing. It simply means that the heaviest or most important information should be at the top – the beginning – of your story, and the least important information should go at the bottom. And as you move from top to bottom, the information presented should gradually become less important.

The benefit of this strategy is that readers immediately learn the primary “news.” Only when they desire to supplement that information do they need to continue reading. Presumably the material follows in descending significance until they either finish the piece or it descends into minutiae of no interest to that particular reader.

The previously linked article notes one extremely important aspect of the inverted pyramid [emphasis added].

The inverted pyramid format turns traditional storytelling on its head. In a short story or novel, the most important moment – the climax – typically comes about two-thirds of the way through, closer to the end. But in news writing, the most important moment is right at the start of the lede.

And it is this traditional sort of storytelling to which we most often turn when we read for pleasure rather than as an obligation.

Reading for Enjoyment

Pleasurable reading is not, by definition, expeditious. It takes its time to tell a story, rather than rushing into a rapid information dump. In fact, when the narrative is savaged by unloading too much background or too many facts, it becomes hard to enjoy even when we want to like it.

Literature, even brief poetry, takes us on a journey. We go somewhere. We are transformed, albeit usually in an unmeasurable way. While the change may be small, it is quite distinct from the difference made by simply learning new facts.

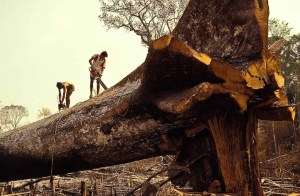

While the journey itself may appear straightforward, in most cases there are often subtle alterations in its course. You might say a story intentionally tends to meander, which is why I titled this post as I have. Meander itself is a curious word.

Like so many words, meander has a literal and a figurative application. In a moment we will see each of these meanings entertainingly illustrated in C.S. Lewis’ correspondence.

I began thinking about this intriguing word when I recently read about its source. It begins with an ancient kingdom in Asia Minor (modern day Türkiye). Lydia was independent for half a millennia before its king, Croesus, was defeated by Cyrus of Persia. One of Lydia’s lasting contributions to civilization came in the form of the minting of coinage.

Herodotus tells us they were the first to do so. This is, of course, a captivating story in its own right.One of the images used on one of their early coins was of the Maeander River, which meandered through their kingdom. The picture above, View of Maeander Valley, was published by Flemish artist Cornelis de Bruyn in 1714.

Did C.S. Lewis Meander?

Searching through Lewis’ writings, I did not find any examples of his use of this winding word. (Let me know if you’re aware of one.)

However, here are two enjoyable examples of his informal use of “meander” in his correspondence. The first, in a 1920 letter to his father, uses the word in its figurative sense.

I have two tutors now that I am doing ‘Greats,’ one for history and one for philosophy. . . . We go to the philosophy one in pairs: then one of us reads an essay and all three discuss it. . . . it is very amusing.

Luckily I find that my previous dabbling in the subject stands me in good stead and for some time I shall have only to go over more carefully ground through which I have already meandered on my own.

In the second occurrence, we find C.S. Lewis writing to his Brother Warnie in 1932. He describes, at some humorous length, the condition of the pond on their property. You can visit this same setting today in the C.S. Lewis Nature Reserve.

I have included the full discussion below. Suburbanites (and even more so, city-dwellers) may not be able to appreciate this story the way that people who have lived in the country can. Still, those with a minute to read the entire passage will likely enjoy the way Lewis meanders through his description of events. Oh, and lest you suffer unnecessary shock, be forewarned that Lewis uses the word “bathe” here not to refer to a “bath,” but to a plunge in the pond.

You will gather from this that summer has arrived: in fact last Sunday (it is Tuesday to day) I had my first bathe. You will be displeased to hear that in spite of my constant warnings the draining of the swamp has not been carried out without a fall in the level of the pond.

I repeatedly told both [the workmen] that the depth of water in the pond was sacrosanct: that nothing which might have even the remotest tendency to interfere with that must be attempted: that I would rather have the swamp as swampy as ever than lose an inch of pond.

But of course I might have known that it is quite vain ever to get anything you want carried out: and the pond is lower. However, don’t be too alarmed. I don’t think it can get any lower than it is now.

I don’t know how much of the draining operations Minto [Janie Moore] has described to you nor whether you understood them. In fact, remembering what a mechanical process described by Minto is like I may assume that the more she has said the less you know about it.

The scheme was a series of deep holes filled with rubble and covered over with earth. Into each of these a number of trenches drain: and from each of these pipes lead into the main pipe now occupying the old ditch between the garden and the swamp, which in its turn, by pipes under the lawn, drains into the ditch beside the avenue.

It was however useless to do all this as long as the overflow outlet from the pond (you know – the tiny runnel with the tiny bridge over near the Philips end of the pond) was meandering – as it did – over all the lower parts of the swampy bit. Nor was it possible to stop this up and deny the pond any outlet, as it would then have been stagnant and stinking in summer, and overflowing in winter.

It was therefore decided to substitute a pipe outlet for the mere channel outlet – which pipe could carry the overflow from the pond, through the swampy bit without wetting it, to the rest of the drainage system. When they first laid this pipe I said that its mouth (i.e. at the pond end) was too low and that it would therefore carry off more water than the old channel and so lower the pond.

The workmen shortly denied this but I stuck to my point and actually made them raise it. Even after they had raised it I was still not sure that it wasn’t taking off more water than the old channel did: so I have now had a stopper made which is in the mouth of the pipe at this moment. I have also given the spring-tap up beyond the small pond a night turned on, and I trust that by thus controlling in-flow and outflow of water I can soon nurse the pond back to its old level.

At any rate I don’t see how it can sink as long as its escape is bunged up. As to the degree of loss at present, as there are no perpendicular banks anywhere it is hard to gauge. I should think that the most pessimistic episode could hardly be more than ¾ of a foot: i.e. a difference one is unconscious of in bathing. Still I grudge every inch.

By the way, it has just occurred to me that the sinking may not be due to the draining at all: for the old ‘channel’ escape, when I looked at it just before the operations began, had certainly widened itself extremely from what I first remembered, and must have been letting out more than it ought. In that case the new pipe may have arrested rather than created a wastage.

One criticism some short-attention-span readers levy against Tolkien’s masterpiece, Lord of the Rings, is that too much time is spent traveling. Such critics overlook the reasons the author presented his saga in the manner he did. Well, for those desiring to simply jump from battle to battle, we now have graphic novels. All of the journeying in LOR has a purpose; it is far from mere “meandering.”

Tolkien detailed the travails of the Fellowship during their quest, and his maps allow students of the mythos to discern “Frodo and Sam traveled over a thousand miles from the Shire to Mount Doom in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, over multiple landscapes and terrains.” One of the colorful words created by Tolkien, that rolls off the tongue like a babbling brook, is the name of a river that crosses the Old Forest: Withywindle. (A withy is an Old English word for a willow, or slender twigs or branches.) Its course may not have been especially winding, but it definitely sounds like it should have been.

No one can deny the influence of J.R.R. Tolkien on fantasy literature. But the aforementioned shortening attention spans do deter some readers. Make no mistake about it, however, the traveling in the writings of the Inklings is not without purpose. Nor does it disrupt the story. Still, the less skilled among us should be cautious about mimicking their techniques. One author describes this hazard in the following way.

Ultimately, when you write, your goal should be to make sure that everything you write doesn’t meander, or in other words, moves in some way towards the conclusion of your story. Be that taking care of a subplot, a character arc . . . whatever, it needs to hit a step, or move towards it, on the path to the ultimate ending of your story.

Remember both pacing and the up and down of rising and falling tension. A meandering story stretches out a low point and breaks the pacing. You always want to keep your plot on a straight line to the ending. The characters, they can wander, as long as the plot doesn’t.

Thanks for meandering with Mere Inkling today. Isn’t it wonderful that God allows us these carefree moments, and life isn’t all about “getting things done?”