With civil discourse in such short supply today, it may be beneficial to consider some wisdom from the past about disagreeing calmly.

If you’re a thoughtful person, and you interact with other rational people, it’s inevitable that you will sometimes disagree. These differences of opinion are not bad things, in and of themselves. They help us sharpen our thinking and occasionally result in someone (from either side) recognizing the errors in their opinions.

There are times, however, when disagreements are not handled respectfully. In such situations, they seldom result in a positive end. In cases where quarrels arise, people don’t persuade others. They do the opposite—they motivate them to entrench themselves and hide behind mental and verbal barricades that reinforce their “errors.”

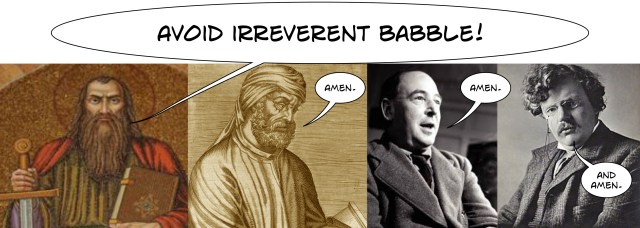

You can go all the way back to the Scriptures to find the recognition that this sort of debate is destructive. Here is the counsel of the apostle Paul to his protégée Timothy, a young pastor:

Remind them of these things, and charge them before God not to quarrel about words, which does no good, but only ruins the hearers. Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth. But avoid irreverent babble, for it will lead people into more and more ungodliness, and their talk will spread like gangrene. (2 Timothy 2:14-17)

In the second century, Tertullian, a brilliant North African Christian scholar, penned one of my favorite passages in all of patristic literature.

I might be bringing forward this objection from a want of confidence, or from a wish to enter upon the case in dispute in a different manner from the heretics, were not a reason to be found at the outset in that our Faith owes obedience to the Apostle who forbids us to enter into questionings, or to lend our ears to novel sayings, or to associate with a heretic after one admonition—he does not say after discussion.

Indeed, he forbade discussion by fixing on admonition as the reason for meeting a heretic. And he mentions this one admonition, because a heretic is not a Christian, and . . . because argumentative contests about the Scriptures profit nothing, save of course to upset the stomach or the brain.

This or that heresy rejects certain of the Scriptures, and those which it receives it perverts both by additions and excisions to agree with its own teaching. For even when it receives them it does not receive them entire, and if it does in some cases receive them entire, it none the less perverts them by fabricating heterodox interpretations.

A spurious interpretation injures the Truth quite as much as a tampered text. Baseless presumptions naturally refuse to acknowledge the means of their own refutation. They rely on passages which they have fraudulently rearranged or received because of their obscurity.

What wilt thou effect, though thou art most skilled in the Scriptures, if what thou maintainest is rejected by the other side and what thou rejectest is maintained? Thou wilt indeed lose nothing—save thy voice in the dispute; and gain nothing—save indignation at the blasphemy. (On the Prescription of Heretics, 16-17)

If you would like to read a fascinating scholarly article on this passage you can download one here. In “Accusing Philosophy of Causing Headaches: Tertullian’s Use of a Comedic Topos,” J. Albert Harrill writes:

Among the most famous passages in Tertullian’s De praescriptione haereticorum (ca. 203) is what appears to be nothing more than a throwaway line. After declaring that ‘heretics’ have no right to use Christian Scripture, he writes, ‘Besides, arguments over Scripture achieve nothing but a stomachache or a headache.’

Previous scholarship has assumed the protest to epitomize Tertullian’s fideism and general anti-intellectualism. However, I argue that the line evokes a comedic stereotype within a medical topos about ‘excessive’ mental activity causing disease in the body, going back to Plato and Aristophanes.

The passage is, therefore, not a throwaway line but an important part of Tertullian’s attempt to caricature his opponents with diseased superstitio (excessive care and ‘curiosity’).

More Recent Variations of this Theme

Those who have attempted serious, rational argument with someone who is unserious or irrational know very well what Tertullian was describing. If you are earnest and calm in your advocacy, only to have your counterpart act flippant or ignorantly obstinate, it really can make one feel nauseous.

G.K. Chesterton, who was an articulate defender of Christianity during the beginning of the twentieth century, described the frustration in a predictably entertaining manner.

If you argue with a madman, it is extremely probable that you will get the worst of it; for in many ways his mind moves all the quicker for not being delayed by things that go with good judgment.

He is not hampered by a sense of humour or by clarity, or by the dumb certainties of experience. He is the more logical for losing certain sane affections.

Indeed, the common phrase for insanity is in this respect a misleading one. The madman is not the man who has lost his reason. The madman is the man who has lost everything except his reason.” (Orthodoxy)

As Chesterton suggests, the madman has retained his ability to reason, but is no longer inhibited by reason itself. I would liken it to retaining the appearance of reasoning, bereft of its essence. It parallels what we read in 2 Timothy 3.

In the last days . . . people will be lovers of self, lovers of money, proud, arrogant, abusive, disobedient to their parents, ungrateful, unholy, heartless, unappeasable, slanderous, without self-control, brutal, not loving good, treacherous, reckless, swollen with conceit, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, having the appearance of godliness, but denying its power. Avoid such people. (Italics added.)

C.S. Lewis also addresses the inability of many who are wrong to conduct rational conversations. Whenever they meet a reasoned argument, they are disarmed.

Unfortunately, their lack of logic does not prevent them from charging into the disputation. They assume their passion or their appeal to subjectivity (i.e. that “everyone” is right) will win the day.

Lewis grew so frustrated by the phenomenon that he coined a new word to identify it. He regrets the passing of the day when you persuade someone of their error before you could legitimately explain why your own position is correct on a given issue.

The modern method is to assume without discussion that he is wrong and then distract his attention from this (the only real issue) by busily explaining how he became so silly.

In the course of the last fifteen years I have found this vice so common that I have had to invent a name for it. I call it Bulverism.

Some day I am going to write the biography of its imaginary inventor, Ezekiel Bulver, whose destiny was determined at the age of five when he heard his mother say to his father – who had been maintaining that two sides of a triangle were together greater than the third – `Oh you say that because you are a man.’

“At that moment,” E. Bulver assures us, “there flashed across my opening mind the great truth that refutation is no necessary part of argument. Assume that your opponent is wrong, and then explain his error, and the world will be at your feet.

“Attempt to prove that he is wrong or (worse still) try to find out whether he is wrong or right, and the national dynamism of our age will thrust you to the wall.” That is how Bulver became one of the makers of the Twentieth Century.

I find the fruits of his discovery almost everywhere. Thus I see my religion dismissed on the grounds that “the comfortable able parson had every reason for assuring the nineteenth century worker that poverty would be rewarded in another world.” Well, no doubt he had. On the assumption that Christianity is an error, I can see early enough that some people would still have a motive for inculcating it.

I see it so easily that I can, of course, play the game the other way round, by saying that “the modern man has every reason for trying to convince himself that there are no eternal sanctions behind the morality he is rejecting.”

For Bulverism is a truly democratic game in the sense that all can play it all day long, and that it gives no unfair privilege to the small and offensive minority who reason. But of course it gets us not one inch nearer to deciding whether, as a matter of fact, the Christian religion is true or false. . . . I see Bulverism at work in every political argument.

Until Bulverism is crushed, reason can play no effective part in human affairs. Each side snatches it early as a weapon against the other; but between the two reason itself is discredited. (“‘Bulverism:’ Or the Foundation of Twentieth Century Thought”)

So, there we have it. We may derive some comfort from the fact that irrational arguing has frequently displaced civil discourse since the dawn of human communication.

As for me, I intend to avoid the Bulverites as much as possible. The last thing I need is a migraine or a serious case of indigestion.