C.S. Lewis wrote: “There is no subject in the world (always excepting sport) on which I have less to say than liturgiology” (Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer).

In Christian usage, the word “liturgy” – derived from leitourgia, and translated “work of the people” or “work for the people” – corresponds to the public worship service.

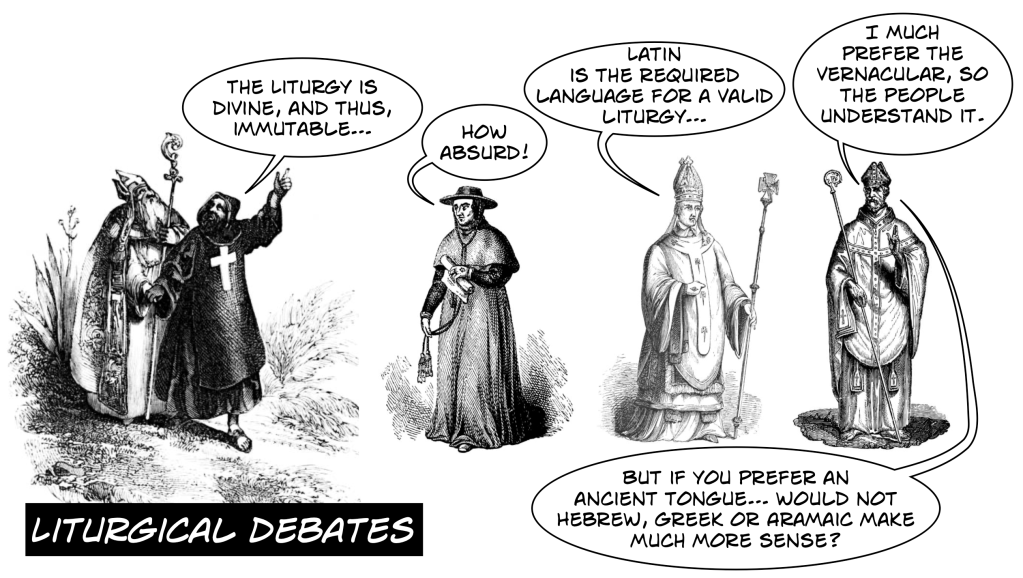

For some, “liturgy” is regarded as a negative word. It may evoke, in such cases, a sense of sterile ritual or what the Scriptures refer to (in the King James Version) as “vain repetitions” (Matthew 6). The irony is that human beings generally prefer familiarity, and almost all worship is essentially liturgical.

Nondenominational churches sometimes claim they do not possess a liturgy. In truth, every nonspontaneous worship experience possesses liturgical elements. They may be simple – a welcome or greeting followed by music, prayer, the reading of a Bible passage, often followed by some form of sermon or reflection. Oh, and for American Protestants at least, it appears most consider “announcements” are essential to worship services.

The particular elements vary, but the “liturgical” aspects, normally occur in the same sequence at regular services.

C.S. Lewis was a faithful member of the Church of England. He was also respectful of tradition, and genuinely content with the Book of Common Prayer. While he did not prefer conventional church hymnody, he acknowledged that it blessed others. In “The Classical Anglicanism of C.S. Lewis,” the author says Lewis challenged “the assumptions of a liberal theology which undermined the Church’s confidence in its proclamation” of the Gospel. However, he continues, Lewis “was no reactionary.”

C.S. Lewis loved the simplicity of church worship in its unostentatious form. That was one reason he faithfully attended services at his modest local parish. He referred to himself as a “very ordinary layman.” This was his humble confession, although there was precious little about the scholar that was “ordinary.” Still, he was reticent to comment on ecclesiastical subjects where he possessed no expertise. Thus his complacency with time proven liturgical matters, and his academic disinterest in commenting on them formally.

This, of course, did not apply to theological truths such as the doctrinal core of “Mere Christianity.” C.S. Lewis was deeply troubled by challenges to historic Christian orthodoxy. His devotion to the faith he had once rejected forced him to come to its defense when theologians diverged from “the path of life” (Psalm 16).

In 1959, C.S. Lewis delivered an address now entitled “Fern Seed and Elephants.” It is profound. [You can listen to a reading of “Fern Seed and Elephants” at C.S. Lewis Essays.]

Invited to speak to some clergy about the threat of liberal theologies undermining the Christian faith, Lewis begins by acknowledging his lack of formal theological training.

I am a sheep, telling shepherds what only a sheep can tell them. And now I begin my bleating.

Many of us who have attended seminary, can attest to his fear that what passes for illumination is too often the opposite.

I find in these theologians a constant use of the principle that the miraculous does not occur. Thus any statement put into our Lord’s mouth by the old texts, which, if he had really made it, would constitute a prediction of the future, is taken to have been put in after the occurrence which it seemed to predict.

This is very sensible if we start by knowing that inspired prediction can never occur. Similarly in general, the rejection as unhistorical of all passages which narrate miracles is sensible if we start by knowing that the miraculous in general never occurs.

Now I do not here want to discuss whether the miraculous is possible. I only want to point out that this is a purely philosophical question. Scholars, as scholars, speak on it with no more authority than anyone else. The canon ‘If miraculous, then unhistorical’ is one they bring to their study of the texts, not one they have learned from it.

If one is speaking of authority, the united authority of all the biblical critics in the world counts here for nothing. On this they speak simply as men; men obviously influenced by, and perhaps insufficiently critical of, the spirit of the age they grew up in.

In Lewis’ The Great Divorce, he describes just such a theologian. If you would like to read my article on this subject, “Confused Clerics: The Landlord’s Stewards in C.S. Lewis’s The Pilgrim’s Regress,” just click on the article’s title.

C.S. Lewis ends his essay “Fern Seeds and Elephants” with a sort of apology. Yet, despite his reluctance to venture into the ecclesiastical realm, he shares the compulsion of the Prophet Jeremiah to speak truth. The prophet, who suffered greatly for his faithfulness, said “If I say, ‘I will not mention [God], or speak any more in his name,’ there is in my heart as it were a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I am weary with holding it in, and I cannot” (Jeremiah 20).

Missionary to the priests of one’s own church is an embarrassing role; though I have a horrid feeling that if such mission work is not soon undertaken the future history of the Church of England is likely to be short.

More Liturgical Wisdom from C.S. Lewis

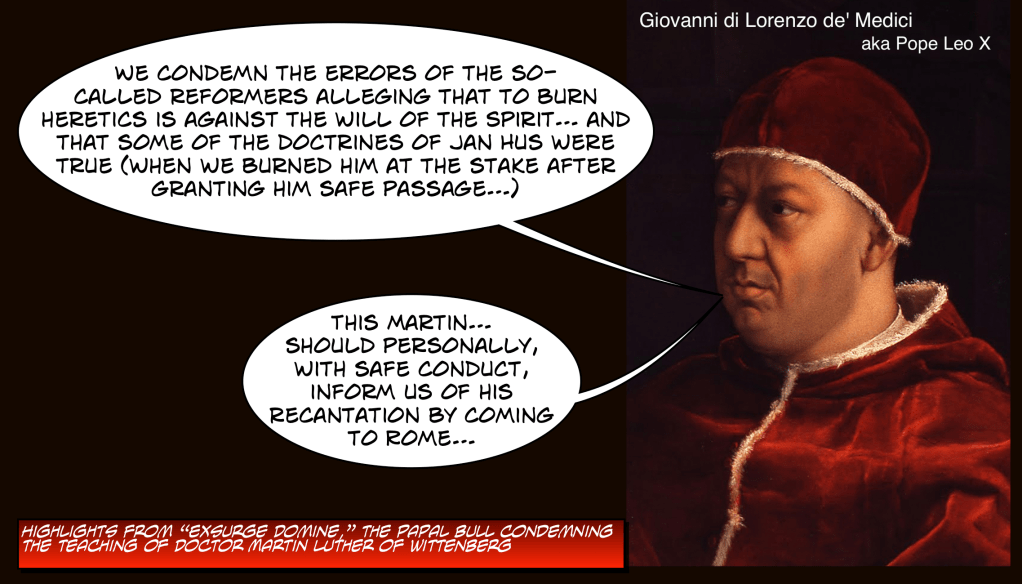

C.S. Lewis did not begin his vocation as a voice of reason for the clergy when he wrote this essay. On the contrary, his concern for the erosion of sound theology began much earlier. A decade earlier he weighed in on a public discussion of arbitrary liturgical changes in the church. Lewis’ concerns at that time remain valid, more than seventy years later.

Sir,– I agree with Dean Hughes that the connection of belief and liturgy is close, but doubt if it is ‘inextricable.’ I submit that the relation is healthy when liturgy expresses the belief of the Church, morbid when liturgy creates in the people by suggestion beliefs which the Church has not publicly professed, taught, and defended.

If the mind of the Church is, for example, that our fathers erred in abandoning the Romish invocations of saints and angels, by all means let our corporate recantation, together with its grounds in scripture, reason and tradition be published, our solemn act of penitence be performed, the laity re-instructed, and the proper changes in liturgy be introduced.

What horrifies me is the proposal that individual priests should be encouraged to behave as if all this had been done when it has not been done.

One correspondent compared such changes to the equally stealthy and (as he holds) irresistible changes in a language. But that is just the parallel that terrifies me, for even the shallowest philologist knows that the unconscious linguistic process is continually degrading good words and blunting useful distinctions. Absit omen!

Whether an ‘enrichment’ of liturgy which involves a change of doctrine is allowable, surely depends on whether our doctrine is changing from error to truth or from truth to error. Is the individual priest the judge of that? (Church Times, 1 July 1949).

In The Screwtape Letters, an experienced devilish tempter is training a subordinate. In Letter XVI, he discusses attending a church with which his target “is not wholly pleased.”

Laying aside the matter of the futility of ever finding a perfect church – after all, they are made up of people – the letter cautions us about some of the criticisms related to the topic at hand. Since many aspects of Screwtape’s vile advice relate to our own vulnerabilities, I will close with an admittedly lengthy excerpt from the correspondence.

My dear Wormwood, You mentioned casually in your last letter that the patient has continued to attend one church, and one only, since he was converted, and that he is not wholly pleased with it. May I ask what you are about? Why have I no report on the causes of his fidelity to the parish church? Do you realise that unless it is due to indifference it is a very bad thing?

Surely you know that if a man can’t be cured of churchgoing, the next best thing is to send him all over the neighbourhood looking for the church that ‘suits’ him until he becomes a taster or connoisseur of churches. The reasons are obvious. In the first place the parochial organisation should always be attacked, because, being a unity of place and not of likings, it brings people of different classes and psychology together in the kind of unity the Enemy [in Screwtape’s case, the Enemy to whom he refers, is God] desires. The congregational principle, on the other hand, makes each church into a kind of club, and finally, if all goes well, into a coterie or faction.

In the second place, the search for a ‘suitable’ church makes the man a critic where the Enemy wants him to be a pupil. . . . [One nearby congregation boasts a] Vicar is a man who has been so long engaged in watering down the faith to make it easier for a supposedly incredulous and hard-headed congregation that it is now he who shocks his parishioners with his unbelief, not vice versa. He has undermined many a soul’s Christianity. His conduct of the services is also admirable. In order to spare the laity all ‘difficulties’ he has deserted both the lectionary and the appointed psalms and now, without noticing it, revolves endlessly round the little treadmill of his fifteen favourite psalms and twenty favourite lessons. . . .

[While encouraging church shopping], all the purely indifferent things – candles and clothes and what not – are an admirable ground for our activities. We have quite removed from men’s minds what that pestilent fellow Paul used to teach about food and other unessentials – namely, that the human without scruples should always give in to the human with scruples.

You would think they could not fail to see the application. You would expect to find the ‘low’ churchman genuflecting and crossing himself lest the weak conscience of his ‘high’ brother should be moved to irreverence, and the ‘high’ one refraining from these exercises lest he should betray his ‘low’ brother into idolatry.

And so it would have been but for our ceaseless labour. Without that the variety of usage within the Church of England might have become a positive hotbed of charity and humility.