Odds are that you, kind reader of Mere Inkling, are a pundit. While the overpaid professionals who overpopulate the media would like for us to think being a pundit requires possessing special knowledge or expertise, that’s simply not true.

Any of us who make comments or pass judgments in an authoritative manner can rightly be deemed a pundit. If you are simply a commonplace critic, you probably qualify for the title. All the more so if you publish your thoughts.

If the recent elections proved anything, they revealed there may well be more pundits per cubic acre in the modern world, than there are bees.

Recently I came across a peculiar essay, written by a writer with whom I’m totally unfamiliar. David Harsanyi is a senior editor of The Federalist, although this article appeared in National Review. Presumably he is a conservative, but of the atheist variety. (No wonder I haven’t read any of his work.)

At any rate, he’s a journalist who describes his “line of work” as “punditry.” Punditry as we have noted, has become all the rage in our modern era. I’m debating though whether adding it to one’s resume would be beneficial. It appears that receiving the validation of a punditry paycheck is the best gauge for making that determination.

As soon as people had the leisure time to develop their senses of humor, the seeds of punditry were planted, and many a silver tongued cynic has reaped the harvest. The past has known people who offered social criticism with a dash of wit (typically of the sarcastic variety).

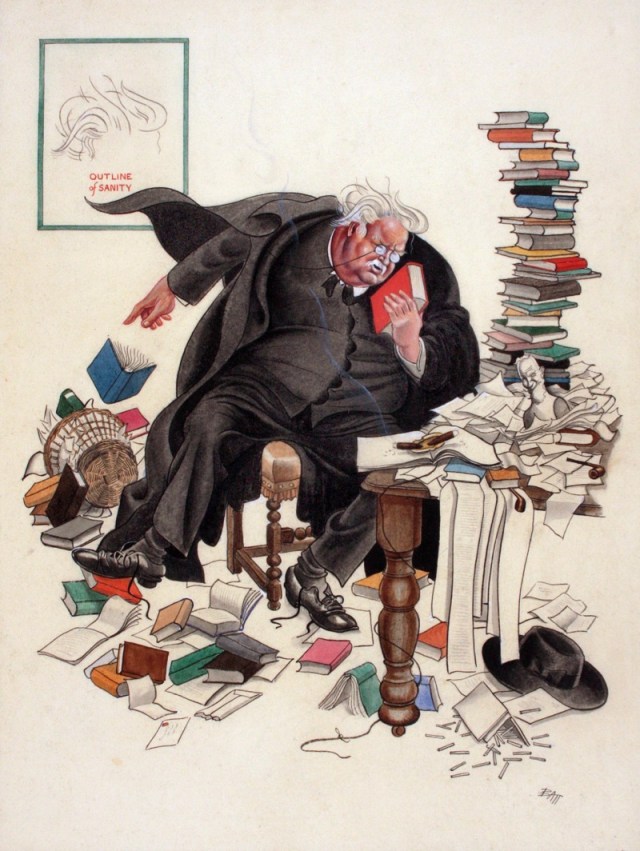

An admirable example of such was G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936). Chesterton differed from Harsanyi in that he was also a philosopher and poet, not merely a journalist. Most notably, Chesterton was also a Christian.

C.S. Lewis held Chesterton in very high regard, and included his book The Everlasting Man among the top ten titles which had influenced his professional and philosophical thought. You can download an audio copy of that text here.

There is a great essay here that explores the influence of Chesterton’s essay “Ethics of Elfland” on the Inklings.

Jerk Logic

Returning to the article with which I began, “Jerk Logic” is the title of Bersanyi’s essay. He began with a question that more people should probably ask themselves.

Am I a jerk? You may find this an odd question for a person to ask himself. But when you’re in my line of work—which, broadly speaking, is called punditry—complete strangers on social media have little compunction about pointing out all your disagreeable character traits.

I found his article interesting for several reasons. He’s candid about some of the booby traps that endanger those who dare to write about controversial subjects. He offers a confession about just how soul-scarring the past election has been for some who have followed its permutations closely.

The 2016 election, I’m afraid, has convinced me that the joke is definitely on me. But after taking meticulous inventory of my actions over the past year or so, I am forced to acknowledge that perhaps, on occasion, some of my behavior might be construed as wantonly unpleasant. Long story short, I am a jerk . . . with an explanation.

Another thing I enjoyed in the brief piece is how he turned to a personality inventory (similar to the Myers Briggs Type Indicator) to assess his potential jerk quotient.

As I learned more about my personality type, I began feeling sorry for everyone in my almost certainly beleaguered family. While we pride ourselves on “inventiveness and creativity” and “unique perspective and vigorous intellect,” Logicians can also be “insensitive,” “absent-minded,” and “condescending.”

The essay concludes with a justification for a modest amount of jerkiness when living the life of a journalist, and especially a pundit.

As a writer, it’s incumbent on me to be clinically unpleasant and prickly when focusing on self-aggrandizing do-gooders or abusers of power or those who pollute our culture with garbage. One can make arguments in good faith while still being downright disagreeable. So I make no apologies for being disliked. There’s nothing wrong with being hated by the right people.

There are, in fact, far too many journalists overly concerned about being shunned. As a young critic writing his first reviews for a wire agency, I sometimes wrestled with an existential question: “Who am I to say these horrible things about people who are far more successful and powerful than I am?” Nowadays I ask myself: “How exactly can I say more horrible things about these people who shouldn’t be more successful or powerful than any of us?”

A skeptical and contrarian disposition is not only useful if you want to be a decent pundit, but indispensable if you want to be a good journalist on any beat.

I wonder whether Chesterton would think of this as an indispensable journalistic trait. He did, after all, have an honest view of the overall profession. “Journalism largely consists in saying ‘Lord Jones is dead’ to people who never knew Lord Jones was alive.” (The Wisdom of Father Brown)

I did find a fascinating description of the press provided by Chesterton in “The Boy.” It was published in 1909 in All Things Considered . . . and echoes true a century later.

But the whole modern world, or at any rate the whole modern Press, has a perpetual and consuming terror of plain morals. Men always attempt to avoid condemning a thing upon merely moral grounds.

If I beat my grandmother to death to-morrow in the middle of Battersea Park, you may be perfectly certain that people will say everything about it except the simple and fairly obvious fact that it is wrong.

Some will call it insane; that is, will accuse it of a deficiency of intelligence. This is not necessarily true at all. You could not tell whether the act was unintelligent or not unless you knew my grandmother. Some will call it vulgar, disgusting, and the rest of it; that is, they will accuse it of a lack of manners. Perhaps it does show a lack of manners; but this is scarcely its most serious disadvantage.

Others will talk about the loathsome spectacle and the revolting scene; that is, they will accuse it of a deficiency of art, or æsthetic beauty. This again depends on the circumstances: in order to be quite certain that the appearance of the old lady has definitely deteriorated under the process of being beaten to death, it is necessary for the philosophical critic to be quite certain how ugly she was before.

Another school of thinkers will say that the action is lacking in efficiency: that it is an uneconomic waste of a good grandmother. But that could only depend on the value, which is again an individual matter.

The only real point that is worth mentioning is that the action is wicked, because your grandmother has a right not to be beaten to death. But of this simple moral explanation modern journalism has, as I say, a standing fear. It will call the action anything else—mad, bestial, vulgar, idiotic, rather than call it sinful.

Amen. Evil acts today are nearly always attributed to some shortcoming or flaw such as insanity (e.g. individual acts) or delusional indoctrination (e.g. jihadism). While these are sometimes contributing factors, Chesterton rightly assessed the base cause.

Sadly, by affirming that fact, I expect that I too will be going on some people’s “jerk” list. They may consider me contrarian, but I’m simply striving to be honest.

We, like our friends practicing “jerk logic” on social media, are usually windmilled precisely at the place of our own judgments of others. thanks!

Brilliant insight. We do cut people lots of slack when we agree with their positions.

This past year has actually reinforced my belief, however, that we must practice greater civility in our conversations with those with whom we disagree.

I don’t mean we should compromise our valid positions, or withhold from including a bit of wit when appropriate… But always communicating civilly as possible.

I just thought of a good example. I enjoy reading editorial cartoons from a wide range of perspectives. That includes talented critiques of my own viewpoint. What I don’t appreciate–from either direction–are cheap shots.

Liberty is based on truth and respect. I think that’s why many in our culture struggle with real freedom; because it is easier to kill truth than simply be humble and learn, or apologize. thanks for feedback!

Another keen insight. Thanks.

Hello Rob,

Working among people is a privilege and a challenge, right?

Thank you,

Gary

True, and the sense of which predominates vacillates from day to day…

Sadly, these days “truth” seems to be what each particular group of people agree on and accept – of course that’s an issue when groups with opposing views and “truth” encounter each other.

You know those lists of words that everyone hopes they will never hear ever again because they have been overused or misused so much? It seems that “truth” may be headed that way as no one know what it means any more/can agree on the definition.

Wonderful post. Love that last paragraph.

You’re right about “truth” getting drug through the mud, as a word. I thought it was bad enough when it was treated in a pedestrian fashion, when in fact it is essential to all knowledge and vital to all healthy relationships.

Oddly, as I was pondering your observation, I thought of a long-forgotten television trope. It came from Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In. It was Lilly Tomlin’s character, the little girl named Edith Ann, who would always babble on about any childish concern and invariably end her monolog with “and that’s the truth.” This five second clip offers only the beginning and ending of a typical skit.

I loved Edith Ann!

Back when comedy was witty and funny and people could laugh at themselves – and could even recognize and laugh at satire

Thanks for the grins

The millennialists, Gen Xers, etc. are just shaking their heads now in disbelief. Seriously, even the social satire in the show was typically offered in a gentle-spirited way.

Pingback: Chesterton, Tertullian and C.S. Lewis on Arguments « Mere Inkling