If you were a Scandinavian living a millennia ago, you would be faced with a critical decision. Would you embrace Jesus Christ and a new life based on mercy, or would you cling to Odin and the Norse pantheon, with its glorification of bloodshed?

When I first heard this choice posed as a choice between the “White Christ” and the blood-drenched Thor, I assumed the white color alluded to traits commonly associated with it today—e.g. purity, innocence, and holiness.*

To my surprise, I recently learned there was a completely different to the Vikings. For them, referring to Christ as “white” was a term of derision.

Before returning to the Northmen, let’s consider for a moment the Inklings. These brilliant writers were well acquainted with white as a biblical metaphor for holiness, etc. They understood how the miracle of the Transfiguration described Jesus’ radiant face shining “like the sun” as the “bright cloud overshadowed them.”

As Mark records in his Gospel, Jesus “was transfigured before them, and his clothes became radiant, intensely white, as no one on earth could bleach them.”

It is no accident Tolkien’s Gandalf the Grey returns as Gandalf the White following his deadly battle with the Balrog.

In C.S. Lewis’ Voyage of the Dawn Treader, Aslan manifests himself to the children as an unblemished lamb.

But between them and the foot of the sky there was something so white on the green grass that even with their eagles’ eyes they could hardly look at it. They came on and saw that it was a Lamb. “Come and have breakfast,” said the Lamb in its sweet milky voice. . . .

“Please Lamb,” said Lucy, “is this the way to Aslan’s country?”

“Not for you,” said the Lamb. “For you the door into Aslan’s country is from your own world.”

“What!” said Edmund. “Is there a way into Aslan’s country from our world too?”

“There is a way into my country from all the worlds,” said the Lamb; but as he spoke his snowy white flushed into tawny gold and his size changed and he was Aslan himself, towering above them and scattering light from his mane.

On the other hand, C.S. Lewis tosses us a curve with the White Witch in his Chronicles of Narnia. The reason for her identification with white is obvious, since she is holding Narnia in an austere, perpetual winter. The witch’s hue carries other messages. Her unthreatening appearance moves Edmund to drop his defenses during their initial encounter.

[Queen Jadis was] a great lady, taller than any woman that Edmund had ever seen. She also was covered in white fur up to her throat and held a long straight golden wand in her right hand and wore a golden crown on her head. Her face was white—not merely pale, but white like snow or paper or icing-sugar, except for her very red mouth. It was a beautiful face in other respects, but proud and cold and stern.

Northern Mythologies

C.S. Lewis was enraptured by Northernness. He and Tolkien spent many hours reading Viking sagas.

However, Lewis was inspired not by the warrior Thor, but the person of Baldur. Several of my online friends and acquaintances have also written about Lewis’ affinity for Baldur. These include Brenton Dickieson, Eleanor Parker, and Bradley Birzer.

Turning from Baldur (Baldr) the Brave to Thor (Þórr), the god of thunder, we find the Norse deity with the largest number of followers. Thor was the ideal divinity for independent adventurers, warriors and violent raiders.

The story of the heroic thunder god still resonates today, as the success of the recent cinematic blockbusters attests. To suit contemporary tastes, the bloody red giant-slayer of myth has shed his more gruesome traits. They have been replaced by nobler aspects, as befitting a modern superhero protecting Midgard (Earth) from danger.

But the medieval period was not the relatively safe world we know. And pleas to turn the other cheek sounded like utter foolishness. The belligerent nature of the Germanic and Scandinavian chieftains of the era, resulted in a modification of the Gospel which was shared by some evangelists. In order to impress a militant population, the pacific nature of Jesus was downplayed. In “Why Trust the White Christ?” we read, “Not until the 1100s did the concept of the suffering Christ take root in Scandinavia; before that Christ was depicted as a triumphant prince—even on the cross!”

Eventually the Gospel would triumph, but one of its first effective renditions for the northern barbarians came in a gospel harmony⁑ entitled the Heliand. A number of references to the Gospel in J.R.R. Tolkien’s academic writings reveals his familiarity with the Old Saxon work, which he also mentioned in his lectures. The Heliand was commissioned by Charlemagne’s grandson Louis the German (806-876) to reach the Franks’ fellow Germanic tribes who remained Pagan. It was written by a Benedictine monk named Notker, who also wrote The Life of Charlemagne.⁂

The fact that this alliterative Gospel (in poetic form) was composed for the Saxon warrior class (their nobility), makes it particularly interesting. Knowing it was recited not only in monasteries, but also mead halls, makes one’s personal reading of it feel like a journey into the ancient past.

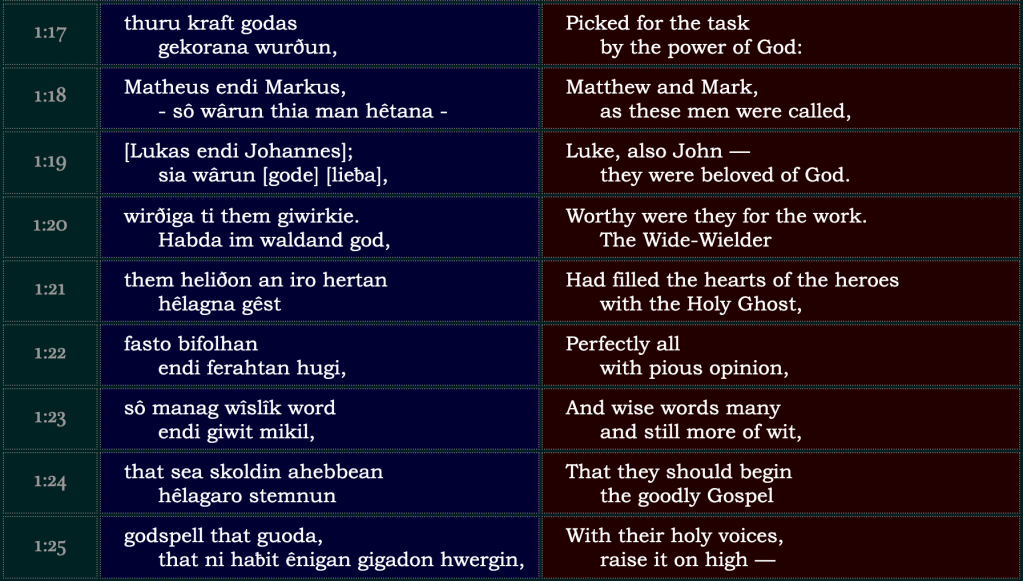

Mariana Scott’s 1966 translation ⁑⁑ is available here. This site posits her translation beside the original Old Saxon. One of my favorite passages comes in the “introduction,” as the context of the Gospel proper is set for the hearers. It is very serious and describes the four Evangelists as inspired by God.

[The Lord] had filled the hearts of the heroes,

with the Holy Ghost.

Perfectly all,

with pious opinion,

And wise words many

and still more of wit.

That they should begin

the goodly Gospel

With their holy voices,

raise it on high—

The Question of the White Christ

Referring to Jesus as the “White Christ” may have been related to the association of white baptismal robes worn by the newly baptized. But it involved more than that.

Apparently, the appellation “white,” especially when linked to Christ, was a Pagan insult. In a Scandinavian Studies article entitled “The Contemptuous Sense of the Old Norse Adjective Hvítr, ‘White, Fair’” we learn that it possessed a pejorative sense.

The [Old Icelandic] heathen religion glorified physical strength and courage in combat, a direct antithesis to the Christian ideal of pacifism based upon the Golden Rule. Hence, the heathen Icelanders interpreted the Christian Hvítakristr ‘The White Christ’ as a cowardly, contemptible counterpart of Thor, the god of courage and strength . . .

And this negative connotation continued, even after the triumph of the new faith.

[Even] after Christianity had become established as the national religion in Iceland, this heathen conception of Christian ‘cowardice’ disappeared but left its traces in the epithet hvítr, especially when one wished to belittle or vilify a personal enemy.

. . .

The double sense (‘fair’ : ‘cowardly’)was characteristic of skaldic poetry and served to enhance the sarcastic effect.

And thus my youthful innocence about the meaning of the White Christ has been dispelled. But, at the same time, my insight into the historic prejudice against the sacrificial Son and Lamb of God has grown.

Jesus was no coward, but he is—now and forever—pure, innocent, and holy.

* It should go without being said that associating the color white with Jesus has absolutely nothing to do with ethnicity. The Incarnation of our Lord makes it abundantly clear that Jesus was a Jew born in Bethlehem and raised in Nazareth. The Bible describes nothing noteworthy about his appearance that would distinguish him from the rest of the Jewish people in ancient Palestine. Thus, whatever Jesus’ complexion, he would have looked little like the pale Anglo-Saxon messiah we have often seen in paintings and cinema.

⁑ A Gospel harmony is a blending together of the four canonical Gospels into a single account. Tatian (c. 120-180), an Assyrian theologian, compiled the Diatessaron, which was prominent in the Syrian church, and is thought to have directly influenced the Germanic harmony, the Heliand.

⁂ Notker (c. 840-912) who also composed hymns and poetry. As mentioned above, the Benedictine monk also wrote The Life of Charlemagne which records many fascinating stories about Frankish and Germanic Christianity. Apparently a poor precedent was set by Frankish generosity when a group of Northmen serving as envoys received baptism.

As I have mentioned the Northmen I will show by an incident drawn from the reign of your grandfather in what slight estimation they hold faith and baptism. . . .

The nobles of the palace adopted them almost as children, and each received from the emperor’s chamber a white robe and from their sponsors a full Frankish attire, of costly robes and arms and other decorations.

This was often done and from year to year they came in increasing numbers, not for the sake of Christ but for earthly advantage.

A very enlightening and sadly entertaining account. But what happens when the gifts run out?

⁑⁑ In the foreword to her translation, Scott shares some intriguing thoughts on the challenging labor of translation.

It was important for me to remember that the Heliand was originally intended for recitation. This accounts for the very great emphasis on rhythm. While the exact form of the old alliterative verse, though common to both early English and German poetry, proved too confining, a freer adaptation was possible. Let us remember that much of the effect of modern free verse depends on the interplay of sounds: assonance and alliteration.

Keeping in mind the purpose of the original, I read my translation aloud as I worked, repeating lines several times, varying and checking rhythms, trying to imitate the surge of the meter and yet avoid monotony. The end result was a line of variable feet, usually a rather free alternation of anapests and iambics with a few scattered tribrachs and spondees, divided by the traditional caesura.

I aimed for an alliteration of at least one accented syllable in the first half line with one accented syllable in the second half. If more sounded right, I was delighted. If none worked, I tried to make the rhythm carry the line along to the next cadence. Not all of it, I painedly admit, turned out to be poetry—but then not all of the Old Saxon is!

Hi Rob,

What courage it takes ti save the world from a fallen nature no one else could redeem. Sure, Thor can take life, but only Christ can give life and life eternal .

In Christ,

Gary

The greatest of their many differences.

This all makes perfect sense. How fascinating and illuminating.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. I find this subject fascinating and knew nothing about the Heliand before researching for this post. Likewise the pejorative use of that particular word for “white” by the Vikings.

As a pastor I once had to counsel with some young neo-Nazi’s, to the extent of exorcism. What you have shared makes so much sense. Thank you.

In preparing this post I debated including some information about the revival of Heathenism, and the way that some racists seek to co-opt the essentially colorblind Ásatrú for their own agenda.

A helpful article on that subject can be found here: “What To Do When Racists Try To Hijack Your Religion”

Thank you for sharing your experience, Erroll.

Interesting post, when you’re on the ground that is familiar to you, but it falls down when you start writing about Thor and Odin.

Thor isn’t my favourite Norse god, but there’s a lot more to him than merely a blood-soaked warrior (in fact I don’t recall any legends of him slaying any giants, nor do I recall him being referred to as “Red”). He’s quite a complex character. I’d recommend reading Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology for more insight.

Odin is also more complex. He’s the god of wisdom, among other things.

Anyway thanks for the explanation of “the White Christ” — I always wondered about that.

The meme that you shared at the top of the post… well what can I say apart from, sorry about that… it’s hardly constructive interfaith dialogue, is it? But then, I don’t think your response to it is, either, since you have clearly done some research, but not actually gone back to the original Norse myths to find out what they were really about.

Warriors are always going to make everything about war — they used Christianity as a justification for war too (remember the Crusades?) That doesn’t mean that their version of a religion is the only one that exists. The first rule of interfaith dialogue is, compare like with like.

Thank you for your thoughtful response to this post, Yvonne. (I hoped I might hear from you, and I say that honestly.)

I agree with your point about military minds resonating with military imagery. Christian theology has indeed developed a Just War Theology, but (1) it has very specific limitations, and more importantly, (2) no one directly attributes it to Jesus. Thus, no Christians I know would argue that the Crusades were inspired by the Jesus himself.

To put it another way—relating directly to the theme of my post—when you compare the two beings, they have little in common. One vivid example: impossible to conceive of the thunder god advising someone to “turn the other cheek.”

I should admit that my active knowledge of the Norse gods comes from reading the original mythologies back in my teens. But, being proud of my own Nordic roots, I have read major portions of the Eddas during the past two decades. I was aware of Gaiman’s treatment, but understand it to be a novel (i.e. a fictional treatment).

As for giants… I guess the last generation of scholars who translated Jötunn as giants misled me (and many others). ’Tis not giants that populate Jötunheimr, I now understand. But, formerly I’d understood Geirröðr the Jötunn killed by Thor to be a giant.

Thanks again for the comment and (constructive) criticism.

Thanks for this reply, which (imho) is much more nuanced than the original post.

Good to know that you have read the Eddas. I’ve read them and Gaiman’s treatment (not a novel but a retelling and a very good one). I’ve also read the Gospels — I have to admit that was over 30 years ago. Again, two pieces of literature that are performing very different functions.

Thor and Jesus are not similar, it’s true. They are very different archetypes. I prefer Odin to either of them.

You do know that turning the other cheek was an act of resistance to the Roman occupation, I assume?

That is, indeed, one interpretation of Jesus’ reference to turning the other cheek.

I’ve actually been thinking recently about rereading the Eddas.

Fascinating. I never before made the connection between Gandalf’s transformation and the Transfiguration of Christ.

Glad you enjoyed the post, Anna.

Pingback: Free Storytelling Class « Mere Inkling Press

This was intriguing and new to me, Rob. Best wishes!

It’s a rare day when I can introduce the inestimable Dr. Dickieson to something new!