Connecting C.S. Lewis to the pursuit of nuclear weapons by Iran’s mullahs admittedly sounds like a protracted stretch. Yet the current conflict between Iran and Israel does have one astonishing element that does link the great Oxbridge professor with the conflict.

If you’re familiar with Lewis’ writings, you might logically assume the connection relates to his writing on nuclear weapons. After all, in 1948 he wrote an essay entitled “On Living in an Atomic Age.” The matter is even more acute since we moved from the era of relatively minuscule A-bombs into a time when humanity’s H-bombs, employing fusion rather than mere fission, are thousands of times more deadly.

Lewis discusses some interesting philosophical (and theological) questions in his article. He begins by placing the question within the context of our inherent physical mortality. He writes, “do not let us begin by exaggerating the novelty of our situation.”

Believe me, dear sir or madam, you and all whom you love were already sentenced to death before the atomic bomb was invented: and quite a high percentage of us were going to die in unpleasant ways. . . .

It is perfectly ridiculous to go about whimpering and drawing long faces because the scientists have added one more chance of painful and premature death to a world which already bristled with such chances and in which death itself was not a chance at all, but a certainty.

Don’t let the stoic beginning of his thoughts deter you from reading the essay itself, because C.S. Lewis does not leave us despairing. On the contrary, he offers hope and practical advice for maximizing the meaning of our lives.

Although C.S. Lewis lived into the beginning of the MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) era, he chose not to inject himself into political subjects, lest it detract from his advocacy for the simple Gospel.

Nevertheless, the brief note “C.S. Lewis and Nuclear Weapons,”penned forty years ago by a “peace activist” pastor, conjectures on what the author’s opinion may have been. It is thought-provoking, especially in mentioning a possible link between nuclear destruction and the “deplorable word” referred to in The Chronicles of Narnia.

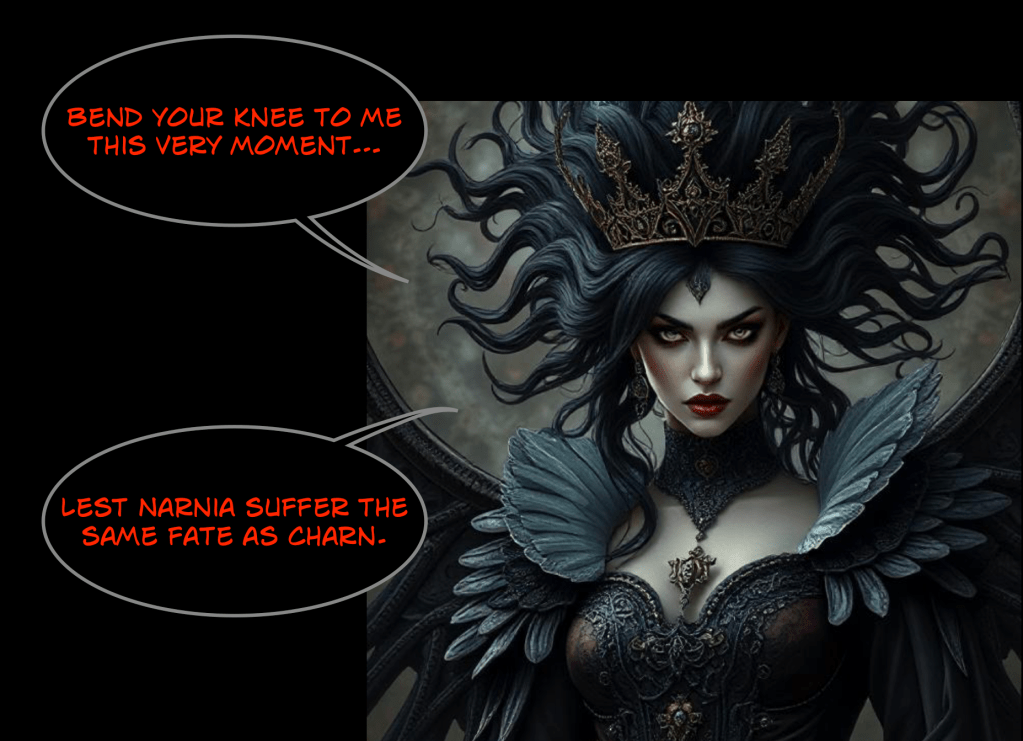

In The Magician’s Nephew, Lewis’ child protagonists encounter a witch queen on the devasted world of Charn. Queen Jadis, when denied the power to rule over the planet, chose to invoke a curse that destroyed every living thing other than herself. “Then I spoke the Deplorable Word. A moment later I was the only living thing beneath the sun.”

While Lewis does not elaborate on the nature of the destructive nature of this most deplorable of powers, Aslan does offer the following caution near the end of the novel.

It is not certain that some wicked one of your race will not find out a secret as evil as the Deplorable Word and use it to destroy all living things. And soon, very soon, before you are an old man and an old woman, great nations in your world will be ruled by tyrants who care no more for joy and justice and mercy than the Empress Jadis. Let your world beware.

So, what does this have to do with Iran & Israel?

Frankly, I find the connection to be especially odd. As you may know, military entities have a propensity to apply nicknames or euphemisms to various things, such as their weapon systems.

This is true for military campaigns or discrete operations. For example, the United States has employed labels like Operation Linebacker (in Vietnam) and Operation Crossroads (for 1946 nuclear weapons tests).

Sadly, Operation Enduring Freedom (in which I personally took part) did not live up to its name. Under the Taliban, Afghanistan has degenerated once again into a primitive morass which abuses its women and children.

A number of distinct operations have taken place during the current war between Iran (and its proxies) and Israel. Operation Rising Lion is Israel’s nomenclature for the various elements of their direct attack on Iran. One independent Jewish news site points out how Benjamin Netanyahu foreshadowed the campaign in May when he said, “the verse in the Tanach that most fits with an existential war? That’s our war – a war of existence . . . A people that rises like a lion, leaps up like the king of beasts.”

Every Israeli military operation has a name, and the Iran attack is now called Am K’lavi, or “a people like a lion” – the exact wording Netanyahu used six weeks ago. English-language publications now refer to the operation as “Rising Lion.”

While this is quite interesting, it is the name assigned to one of the subsidiary operations encompassed by Rising Lion which possesses a genuinely shocking designation.

One initial focus of Israel’s campaign was to eliminate the leading scientists leading Iran’s efforts to pursue a nuclear arsenal. They named this particular facet Operation Narnia.

When I first saw that, I immediately thought I must have misread the title. But no, they actually chose Narnia as the name for the assassinations. At that point I thought they might be referring to some other Narnia. Alas, it doesn’t appear they were alluding to the medieval Italian city whose name inspired C.S. Lewis.

The reason for choosing Narnia as the operation’s title was apparently an intentional reference to the amazing world where so many of us met the awesome and compassionate Aslan. In “‘Operation Narnia:’ How Israeli Intelligence Targeted Key Iranian Nuclear Scientists,” we read:

Israel kicked off Operation “Rising Lion” last Friday, launching a sweeping military assault that dealt a major blow to Iran’s leadership and nuclear infrastructure. . . .

In a surprising detail, the Jerusalem Post reports, the component of the mission aimed at Iran’s nuclear scientists was codenamed “Narnia” by Israeli forces – a reference to the fantasy realm, underscoring how bold and unlikely such a strike might have seemed before it was executed.

Another intriguing rationale for entitling the Operation after C.S. Lewis’ creation is even more provocative. The Substack blog Wardrobe Door proposes a supernatural consideration for the choice of “Narnia.”

The [Jerusalem] Post says the name “reflects the operation’s improbable nature, like something out of a fantasy tale rather than a real-world event.” One could also imagine it involved deep espionage tactics that may have had soldiers sneaking in areas as if through a magical wardrobe.

Whatever tactics may have been used in Operation Narnia, it is intriguing to consider how the power of C.S. Lewis’ vision has spread across national boundaries. May all people heed Lewis’ witness to humanity’s Savior, for surely,

God cannot give us a happiness and peace apart from Himself, because it is not there. There is no such thing (Mere Christianity).