Don’t be surprised, but many clergy possess keen senses of humor. Sure, there are staid, grimacing ministers who consider acting dour to be a virtue. (They’re often legalistic.) But most of the pastors and military chaplains I’ve worked beside, love to laugh. I think I’ve written enough about humor to verify that.

C.S. Lewis maintained strong bonds with a number of clergy, from a variety of denominations, and that would hardly have been true if they had lacked a sense of humor. Humor, to Lewis, is an essential part of life. He proclaims this truth from the lips of Aslan himself, as the newly created Talking Animals hear the first (accidental) joke.

“Laugh and fear not, creatures. Now that you are no longer dumb and witless, you need not always be grave. For jokes as well as justice come in with speech.” (The Magician’s Nephew)

I recently read about a fascinating incident one historian described as “perhaps the only really satisfactory practical joke in the whole history of theology.” Allow me to set the scene.

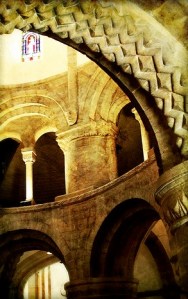

The Byzantine Empire lasted for a thousand years, before being defeated and desecrated* by Islamic armies. During the centuries surrounding its apex, it suffered from the political intrigue and competition with which we are all too familiar.

Photios I was a Byzantine scholar who was twice the Patriarch of Constantinople during the ninth century. Twice is unusual, but it was due to the machinations of emperors and empresses who meddled in the affairs of the church.

He had a troubled relationship with another priest named Ignatius, who also served two times as Patriarch. The good news is that the men were eventually reconciled and both are regarded by Orthodox Christians as saints.

The anecdote comes from the period of their rivalry. Photios, whose brilliance was widely acknowledged, and presumably envied by Ignatius, decided to pull an embarrassing public prank on his nemesis.

Photios devised a bizarre theory that human beings have two souls. His goal was to trick Ignatius into taking it seriously, whereupon Photius withdrew the thesis and admitted he had not been serious. Apparently, everyone unsatisfied with Ignatius’ leadership found it quite entertaining.

Fortunately, among clergy the humiliation of others is rarely the object of humor. Yet, sadly, I have seen it attempted. I personally repent of ever having done so myself, and regard it as sharing, along with vulgarity and blasphemy, the lowest level of “humor.”

The Wisdom of Lewis

In Reflections on the Psalms, C.S. Lewis relates something I know to be true from my own experience.

A little comic relief in a discussion does no harm, however serious the topic may be. (In my own experience the funniest things have occurred in the gravest and most sincere conversations.)

Clergy deal with serious topics, like death, quite frequently. Perhaps that is one reason a well-developed sense of humor is common among their ranks.

Skip this footnote if you want to end on a “happy” note.

* “Desecration” may sound like a harsh word to our interfaith-sensitive ears, but it is accurate here. Islam is rarely a gentle master for Christians, and it has been common to see churches and holy places seized and converted to foreign religious uses. For example, in the capital Constantinople (now called Istanbul), Orthodox Christianity’s most magnificent church, Hagia Sophia, saw much of its glorious and historic iconography destroyed when it was converted to a mosque. Many years later, in 1934, an enlightened Turkish government ended the insult, and chose to treat the holy place as a museum. Sadly, the current regressive government under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, reversed that decision, and in 2020 the Church of Holy Wisdom was returned to its usage as a mosque.