It’s often said that “writing is a solitary task.” I find that’s only half true.

Sure, each individual is responsible for putting the words on the page (AI-cheats aside), but sharing your work with others before publishing it provides amazing dividends.

Not only can “other eyes” see flaws we are too close to the piece to recognize, good critiques often include suggestions to make our writing stronger.

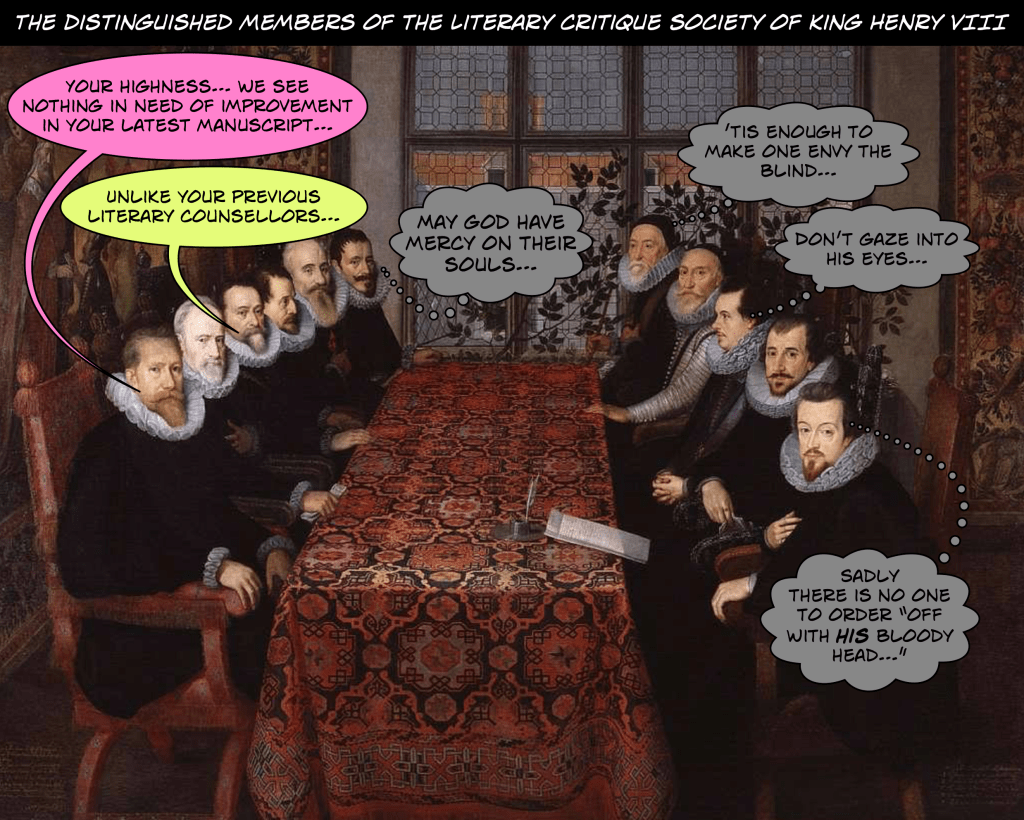

I’ve occasionally described the benefits I’ve received from being a member of writers [critique] groups around the globe. I titled one of my posts “Be an Inkling,” because this mutual sharing was central to those brilliant minds who gathered together in Oxford.

In 1967, J.R.R. Tolkien described his reason for using that particular word in just such settings. He said he used the word Inkling as “a ‘jest,’ because it was a pleasantly ingenious pun in its way, suggesting people with vague or half-formed intimations and ideas plus those who dabble in ink.”

I too find it “pleasantly ingenious” and have echoed it here in my own domain.

Conferences can be helpful too, but my experience is that nothing surpasses the encouragement that emanates from the mutual commitment shared by writers who physically gather to share their creations.

I noted above two concrete ways writing friends can contribute to strengthening our work. However, this third element – encouragement – cannot be underestimated. It was precisely this element that brought that masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings, to the world’s attention.

A Pilgrim in Narnia provides a superb account of C.S. Lewis’ essential role in boosting the confidence of his friend J.R.R. Tolkien. He cites a letter in which Tolkien describes how Lewis’ most precious gift was in challenging him to complete his opus.

The unpayable debt that I owe to him was not ‘influence’ as it is ordinarily understood, but sheer encouragement. He was for long my only audience. Only from him did I ever get the idea that my ‘stuff’ could be more than a private hobby. But for his interest and unceasing eagerness for more I should never have brought The L. of the R. to a conclusion.

Melancholy Transitions

Critique groups are weighing on my mind, since the one I’ve been part of for many years has come to its end. The passing of various members during the past decade left too few of us to continue, and we few who were left are mourning the fact that it was not sensible to continue meeting regularly.

It is another reminder of Solomon’s wisdom when he wrote, “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven.”

Sadly, I lack the energy to help establish another new writing fellowship at this point in my life. Perhaps I will join one of the online communities. Christian Writers looks promising.

I actually participated in an online critique community back when primitive “bulletin board systems” were giving way to the nascent internet. No doubt the modern equivalent would be far better in every way.

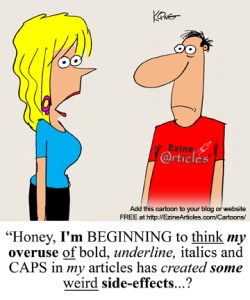

In the meantime, I do have a few readers I trust to review my work before submitting it to an editor. One is my very talented wife. The problem there, however, is that her love (and compassionate nature) make her too gentle when she critiques my work.

This drawback is one side of the coin to which author Dan Brown refers when he says: “I learned early on not to listen to either critique – the people who love you or the people who don’t like you.”

This does not mean, of course, that those who love us are unsuitable candidates. It simply suggests that we need to (often repeatedly) give them permission to offer genuinely critical comments, especially when they are accompanied by suggestions for how we might improve a given passage.

In essence although people like William Faulkner are correct in stating that “writing is a solitary job,” most of us can benefit from sharing our drafts with others.

And fortunate are those of us who discover such friendship, where our writing companions are like-minded, trustworthy, self-confident, and honest. (I personally find having a sense of humor an essential trait, as well.)

In a word, we are greatly blessed to personally become part of our own fellowship of Inklings.