Learning is fun. Education can be enjoyable too. But obviously, they are not the same.

C.S. Lewis wrote a great deal about learning. A master of metaphors, he brilliantly described two distinct challenges faced by educators. In The Abolition of Man, he stated “the task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts.”

Wheaton professor, Robert McKenzie, offers a concise explanation of Lewis’ keen observation.

‘Cutting down jungles,’ as I understand that phrase, means helping students with passionate convictions to evaluate critically their world views, to examine what lies beneath the personal beliefs they profess.

‘Irrigating deserts,’ conversely, involves nurturing in apathetic or cynical students the hope that there is meaning and purpose in human existence.

Quite true, and I believe Lewis’ insight is more timely today than it was during the past century.

Classical Versus Modern Education

Today I read a passage that reminded me just how dramatically contemporary curricula deviate from the traditional educational materials used before the modern era.

While conducting research for a book about imperial Rome, which I hope to complete this year, I came upon the following passage.

It would have been easy to swell this little volume to a very considerable bulk, by appending notes filled with quotations; but to a learned reader such notes are not necessary; for an unlearned reader they would have little interest; and the judgment passed both by the learned and by the unlearned on a work of the imagination will always depend much more on the general character and spirit of such a work than on minute details.

It appears in Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Babington Macaulay, which is available for free download at Internet Archive.

Macaulay (1834-59) was a prominent British historian and politician. His histories were thoroughly researched and widely respected, especially by those on the (liberal) Whig* end of the political spectrum.

A contemporary of Macaulay described his preparation for writing in poetic fashion. According to novelist William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-63), “he reads twenty books to write a sentence; he travels one hundred miles to make a line of description.”

It appears that, like C.S. Lewis, Macaulay possessed a lasting recollection of all he read.

Returning to our beginning dichotomy – jungles versus deserts – both writers were a product of wide and critical literary study. Their minds were, in a sense, like a “rain forest.” Albeit, with C.S. Lewis it was certainly an orderly, well-tended forest. For some less stably grounded and more scatterbrained, the result is a jungle which requires radical clearing.

Alas, today’s more common problem, the unceasing pursuit of entertainment and distraction, leaves many with barren mental landscapes. In consequence, our calling as parents, educators, and friends, becomes one of irrigating the sparse flora and planting healthy new seeds in the hope that they will one day bloom.

* There is an interesting Mythlore article about C.S. Lewis’ view of history you can read here. In it, the author notes that “Lewis rejected a Whig history of unidirectional progress…” For a succinct article on the dangers of Whiggishness, I recommend “Evangelicals and Whig History” at First Things.

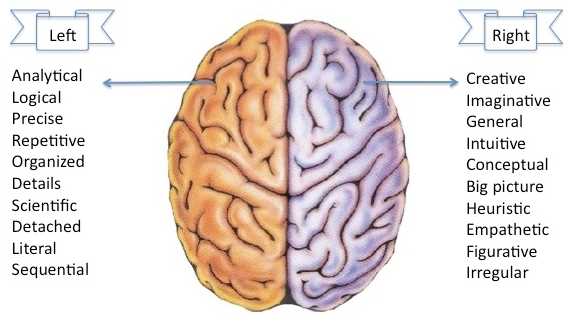

⁑ The brain truly can resemble a jungle, as a “digital reconstruction” reproduced on BrainFacts illustrates.

Immediately recognizable by its intricate folds and grooves, the cerebral cortex is the wrinkly, outer layer of the brain responsible for awareness, perception, and thought. Its interconnected neurons are arranged in six layers, a bit like the layers of tropical rainforests. . . . The findings may bring scientists closer to understanding how the complex jungle of cortical neurons interpret sensory information.