Only three copies of an abridged Bible printed in the United Kingdom remain in existence. To some, their very existence is scandalous. To others, they evidence the desire of Christians to promote spiritual liberation, even for those shackled by human chains.

The sole copy held in North America is in the possession of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Fisk is one of the United States’ distinguished Historically Black Colleges & Universities (HBCUs), and was founded only six months after the end of the Civil War by the American Missionary Association.

Prior to returning the volume to Fisk, this extremely rare Bible was on loan to the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C.* During its exhibition there, the museum described it thusly:⁑

The Slave Bible, as it would become known, is a missionary book. It was originally published in London in 1807 on behalf of the Society for the Conversion of Negro Slaves, an organization dedicated to improving the lives of enslaved Africans toiling in Britain’s lucrative Caribbean colonies.

They used the Slave Bible to teach enslaved Africans how to read while at the same time introducing them to the Christian faith.

A Liberty Fund essay on the volume describes the thought process behind the editing. “The unknown editors intended to steer clear of any revolutionary verses that might spark interest in the idea of liberty,” they say.

For example, the selections from Genesis include the first three chapters, which cover the creation of the world and Adam and Eve in Eden but omits chapter four, which tells the story of Cain and Abel and the first murder.

Even an abbreviated Bible, however, retains the power to communicate a divine message. When C.S. Lewis discussed whether the Bible will become fashionable for secular literary study, he said the challenge would come in the fact that it is, in fact, sacred.

Unless the religious claims of the Bible are again acknowledged, its literary claims will, I think, be given only “mouth honour” and that decreasingly. For it is, through and through, a sacred book.

Most of its component parts were written, and all of them were brought together, for a purely religious purpose (“The Literary Impact of the Authorised Version”).

Because of that, I believe that C.S. Lewis would agree with me that this translation (stunted though it is) would retain the power to enlighten its readers. After all, we are not considering a version of the Bible to which human words have been added. What remains is still inspired.

But in most parts of the Bible everything is implicitly or explicitly introduced with “Thus saith the Lord.” It is, if you like to put it that way, not merely a sacred book but a book so remorselessly and continuously sacred that it does not invite, it excludes or repels, the merely aesthetic approach. . . .

It demands incessantly to be taken on its own terms: it will not continue to give literary delight very long except to those who go to it for something quite different. I predict that it will in the future be read as it always has been read, almost exclusively by Christians (“The Literary Impact of the Authorised Version”).

Thus, I believe the missionaries who devised this edited version of the Scriptures did so with good intent. They would, I am sure, have preferred to deliver to their enslaved hearers the complete Word. However, in cases where slaveowners would bar the Bible altogether because of its themes of rescue, freedom, and the judgment of the powerful, the missionaries compromised their desires.

They deemed the benefits outweighed the compromise. The benefits being the opportunity to learn to read, and even more importantly, the Light that would still shine through the portions of God’s Word to which these precious souls would have access.

As C.S. Lewis noted in a 1952 letter, “it is Christ Himself, not the Bible, who is the true word of God. The Bible, read in the right spirit and with the guidance of good teachers, will bring us to Him.” And, upon making their compromise, these formerly barred missionaries would gain access to those who might otherwise never meet humanity’s Savior, who is the Word incarnate.

So, in order to provide at least a portion of the true Bible, they risked violating the New Testament precedent established in the Book of Revelation.

I warn everyone who hears the words of the prophecy of this book: if anyone adds to them, God will add to him the plagues described in this book, and if anyone takes away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God will take away his share in the tree of life and in the holy city, which are described in this book (22:18-19).

This is a fascinating subject, the various attitudes toward the education of people held in bondage. Various books have been written on the subject, and numerous primary sources describe the differing opinions all those involved. The perspective of “freemen” is particularly poignant. A freeman (or freedman), is a person who has been delivered from a state of slavery.

In the biblical sense, as defined in the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, it is “one who was born a slave and has received freedom” and is commonly used to describe those who were delivered from “bondage to sin [and] presented with spiritual freedom by the Lord.”

For he who was called in the Lord as a bondservant is a freedman of the Lord. Likewise he who was free when called is a bondservant of Christ (1 Corinthians 7:22).

As we used to pray in the liturgy of my childhood – Grant this, O Lord, unto us all!

Online Resources for Further Reflection

Internet Archive not only offers many public domain works for free download. They also host many great texts that you can “borrow” online. Your local library remains a great place, but they probably don’t offer the following books related to this subject.

“When I can read my title clear:” Literacy, Slavery, and Religion in the Antebellum South

Masters & Slaves in the House of the Lord: Race and Religion in the American South, 1740-1870

And, even more exciting, there are some period writings you can read and even download. A quick search turned up a copy of The Duty of Masters: a Sermon, Preached in the Presbyterian Church, in Danville, Kentucky. In 1846, the Rev. John C. Young devoted a significant portion of his message to the responsibility of slaveowners to promote literacy.

The duty of attending to the religious improvement of our servants comprises among others two important particulars – teaching and encouraging them to read God’s word, and inducing them to attend his worship. Many have avowed the doctrine that it is not right to teach servants to read the Bible – and in some of the States their instruction is prohibited by law.

Our posterity will doubtless wonder how so monstrous a doctrine could ever prevail to any great extent in a Christian land; and how good men could ever delude themselves into the belief that such a doctrine was consistent with the first principles of that gospel which is sent to the bond as well as the free, and which requires all who receive it to impart a knowledge of it to the utmost of their ability to all who have it not.

Amazingly, you can even download your own copy of Select Parts of the Holy Bible for the Use of the Negro Slaves in the British West-India Islands from Internet Archives. Determine for yourself whether it was better to share with the captives in the British West Indies these “select parts” or to ignore their plight altogether. A wise man once wrote:

The Church exists for nothing else but to draw men into Christ, to make them little Christs. If they are not doing that, all the cathedrals, clergy, missions, sermons, even the Bible itself, are simply a waste of time.

God became Man for no other purpose. It is even doubtful, you know, whether the whole universe was created for any other purpose (Mere Christianity).

* Coincidentally, the Museum of the Bible will also be hosting a live performance this summer of C.S. Lewis’ “The Horse and His Boy.” Check out the promo on their site to see how they creatively present the equine stars of the book on stage!

⁑ Yes, I understand that the “-ly” appended to “thus” is superfluous, since the word itself is an adverb, but it just sounds so right to my (as C.S. Lewis might appreciate) dinosaur ears.

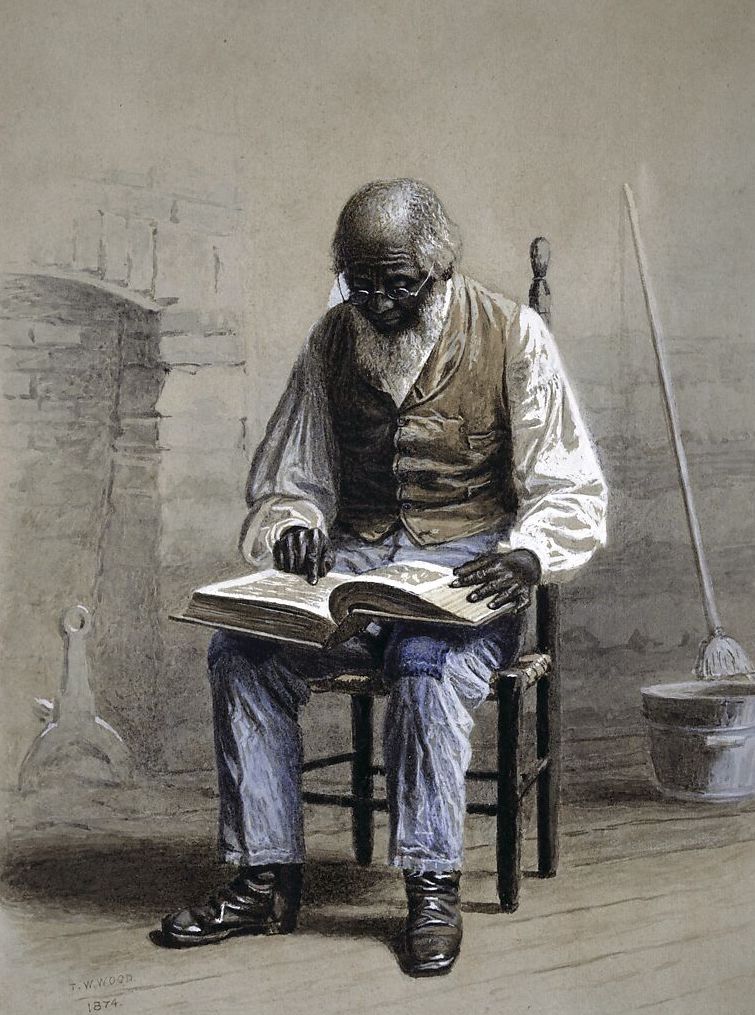

The picture above, “Reading the Scriptures,” was painted in 1874 by Thomas Waterman Wood.