Have you ever carved your initials, or some other pictograph (perhaps a heart?) in the bark of a tree? I never thought much about such things until I learned about the key role played by their bark in a tree’s health. Now I tend to consider this arboreal graffiti* as unfortunate.

I haven’t found any reference in C.S. Lewis to such carvings. However, I suspect that due to his love of nature and hiking, he would discourage the wounding of trees in this way. And there is another reason I believe the Inklings would be wary of this practice. More on that in a moment.

Tree carvings can actually record history for preliterate peoples. I even learned a new word, the meaning of which is easy to decipher from its parts—dendroglyphs. Not all tree scars are considered dendroglyphs. Just those, as Brittanica says, “the dendroglyph [is] an engraving on a living tree trunk. Carved in the usual geometric style, dendroglyphs featured clan designs or made references to local myths. They were used to mark the graves of notable men or to indicate the perimeters of ceremonial grounds.”⁑

One unique people group living “at the edge of the world” faced the fate of most pacifists who are not protected by a benign power. The Moriori lost their island home to the Māori people to whom they were related. Some of their stories survive, partly due to their dendroglyphs.

An academic article on the subject of dendroglyphs is available here.

Dendroglyphs are distinct from scarred trees, the former being decorative marks cut into the bark or heartwood of living trees, while the latter result from resource use, such as bark removal for making implements, obtaining native honey or hunting. A further distinction can be made between two types of dendroglyphs: Indigenous dendroglyphs and dendrograffiti.

Indigenous dendroglyphs are a form of visual expression that reflects affiliation with the land and special cultural association with the landscape and its resources. Dendrograffiti are carvings made by land users, such as shepherds and pastoralists, and often display names, dates, symbols and images that mark boundaries, communications and light entertainment.”

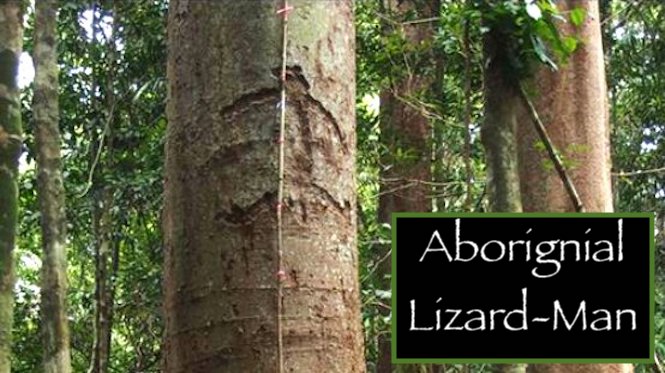

The image above comes from an ancient Australian tree. You can read more about it here, but this is the myth it portrays:

The tale behind the tree has been passed on for generations. It’s the story of two Western Yalanji men who have gone over into Eastern Yalanji country and tried to get a woman. . . . The family of the girl they were trying to take pursued the men.

The Western Yalanji men were chased and speared. One of the men that got speared . . . became a lizard, crawled up the tree and became that carving.

History aside, cutting bark should be avoided in general. And, should you visit a national forest in the United States, be forewarned—“carving into trees is illegal in all national forests!” As the National Park Service pleads: “please respect the law, the trees, and your fellow public land users by not carving words, initials, or anything into tree bark!”

Other Places Where Dendroglyphs are Dangerous

The United States isn’t the only place where a person desiring to mark a tree with a blade should be cautious. This activity is generally inadvisable in both Narnia and Middle Earth.

At Narnia’s very creation, Aslan bestowed sentience on some of the trees of that blessed land. “After Aslan gave certain animals the gift to speech, he declared to the Narnian creatures; “Be walking trees. Be talking beasts. Be divine waters.”

And their creator loved their company. Later we read: “Aslan stood in the center of a crowd of creatures who had grouped themselves round him in the shape of a half-moon. There were Tree-Women there and Well-Women (Dryads and Naiads as they used to be called in our world) who had stringed instruments . . .”

Yet, as gentle as these dryads were, the Witch was able to deceive some of their number. As Tumnus warns the children, “the woods are full of her spies, even some of the trees are on her side.” Still, most continued to follow Aslan, and some of these dryads were among the stone statues restored to life by their lord.

In one of The Last Battle’s saddest scenes, King Tirian is addressed by a tree nymph who warns that Aslan’s imposter is cutting down the forest.

King Tirian and the two Beasts knew at once that she was the nymph of a beech tree. “Justice, Lord King!” she cried. “Come to our aid. Protect your people. They are felling us in Lantern Waste. Forty great trunks of my brothers and sisters are already on the ground.”

“What, Lady! Felling Lantern Waste? Murdering the talking trees?” cried the King, leaping to his feet and drawing his sword. “How dare they? And who dares it? Now by the Mane of Aslan—”

“A-a-a-h,” gasped the Dryad, shuddering as if in pain—shuddering time after time as if under repeated blows. Then all at once she fell sideways as suddenly as if both her feet had been cut from under her. For a second they saw her lying dead on the grass and then she vanished. They knew what had happened. Her tree, miles away, had been cut down.

Narnia is not the only land where trees are damaged at one’s risk. J.R.R. Tolkien populated Middle Earth with amazing creatures. Among these were the Ents.

Ents are not actual trees. They are ancient “shepherds of the trees,” who care for the forests. (The Entwives preferred to care for smaller plants, such as gardens.)

When the hobbits awake Treebeard, he mistakes them for little orcs and is prepared to crush them. Orcs, after all, are destructive by nature and always deserving of a good stomping. When they explain their quest and inform the ancient Ent of Saruman’s burning of their forests near Isengard, he calls on his brethren who respond to the threat.

Treebeard is pleased and says, “Indeed I have not seen them roused like this for many an age. We Ents do not like being roused; and we never are roused unless it is clear to us that our trees and our lives are in great danger.”

I can almost hear Treebeard calling out now, “the Ents are going to war.”

We’ll close now with the marching song of the Ents, and let these words provide a sharp warning to those among us who might contemplate violating trees in the future.

Though Isengard be strong and hard, as cold as stone and bare as bone,

We go, we go, we go to war, to hew the stone and break the door;

For bole and bough are burning now, the furnace roars—we go to war!

To land of gloom with tramp of doom,

with roll of drum, we come, we come;

To Isengard with doom we come!

* I came up with the term “arboreal graffiti” myself, but was pleased to find that other creative minds have also used it online. This post on the subject offers an interesting twist, and is well worth the quick read.

⁑ This quotation is taken from their article on Australian aboriginal art.