Most “word people” like dictionaries. Some writers go so far as to love dictionaries, but I don’t wish to quibble about where one rests on the affection spectrum in terms of these repositories of words.

Most “word people” like dictionaries. Some writers go so far as to love dictionaries, but I don’t wish to quibble about where one rests on the affection spectrum in terms of these repositories of words.

This guy, though, has to be pegged on the extreme (idolatry) end of the meter. Ammon Shea wrote Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages after having done just that. The Oxford English Dictionary, you may know, comprises 25 volumes, and Shea warns that reading it at such a rapid pace took a toll on his eyesight. It’s not surprising, that he admits he is not your typical reader.

One could say that I collect word books, since by last count I have about a thousand volumes of dictionaries, thesauri, and assorted glossaries. . . . I do not collect these words because I want to impress friends and colleagues with my erudition. . . .

My friends know that I read dictionaries for fun, and have come to accept this proclivity with relative good grace, but they are not terribly interested in or impressed by my word collection.

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier advised his fellow poets to read the dictionary. No better way to enrich one’s language, he claimed, although he also read cook books, almanacs and the like. In fact, his biographer offered this fascinating observation.

He found pleasure in the most indifferent novels, as he did in books of the highest philosophical conceptions, and in works of pure science. He was devoured with the desire to learn, and said: “No conception is so poor, no twaddle so detestable that it cannot teach us something by which we may profit.”

C.S. Lewis indicated that so-called “definitions” offered outside the ordinances of the dictionary must be approached warily. “When we leave the dictionaries we must view all definitions with grave distrust” (Studies in Words). He offers a very sensible reason for such precautions.

It is the greatest simplicity in the world to suppose that when, say, Dryden defines wit or Arnold defines poetry, we can use their definition as evidence of what the word really meant when they wrote. The fact that they define it at all is itself a ground for scepticism.

Unless we are writing a dictionary, or a text-book of some technical subject, we define our words only because we are in some measure departing from their real current sense. Otherwise there would be no purpose in doing so (Studies in Words).

Dictionaries are, of course, their own genre. Lectionaries, collections of words and meanings, are different than any other type of written composition. For example, glossaries may draw together specialized vocabulary—say for medical or theological purposes—but by their very nature they are not intended to blaze any new literary pathways.

There is, invariably, an exception to this rule. Some “dictionaries” are creative exercises. They are works of fiction, and some are entertaining indeed.

The most famous of these satirical works is Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary (originally published as The Cynic’s Word Book). The volume is not expressly irreverent, although people of faith will encounter some offensive examples in its pages. However, a number of the entries are brilliant.

Kilt

- A costume sometimes worn by Scotchmen in America and Americans in Scotland.

Rank

- Relative elevation in the scale of human worth.

He held at court a rank so high

That other noblemen asked why.

“Because,” ’twas answered, “others lack

His skill to scratch the royal back.”

Emancipation

- A bondman’s change from the tyranny of another to the despotism of himself.

He was a slave: at word he went and came;

His iron collar cut him to the bone.

Then Liberty erased his owner’s name,

Tightened the rivets and inscribed his own.

Goose

- A bird that supplies quills for writing. These, by some occult process of nature, are penetrated and suffused with various degrees of the bird’s intellectual energies and emotional character, so that when inked and drawn mechanically across paper by a person called an “author,” there results a very fair and accurate transcript of the fowl’s thought and feeling. The difference in geese, as discovered by this ingenious method, is considerable: many are found to have only trivial and insignificant powers, but some are seen to be very great geese indeed.

Another Frenchman, Gustave Flaubert, composed his Dictionary of Received Ideas, which found humor in peculiarities of common understandings.

Absinthe

Extra-violent poison: one glass and you’re dead. Newspapermen drink it as they write their copy. Has killed more soldiers than the Bedouin.

Archimedes

On hearing his name, shout “Eureka!” Or else: “Give me a fulcrum and I will move the world.” There is also Archimedes’ screw, but you are not expected to know what it is.

Omega

Second letter of the Greek alphabet. [Note: this would only apply to biblically literate societies.]

The earliest such example of a satirical dictionary was that by the Persian writer Nezam od-Din Ubeydollah Zâkâni. I have not located a copy of his 14th century lexicon, but it apparently includes entries that are still understandable in our modern world.

Thought

What uselessly makes people ill.

Orator

A donkey.

Word lovers can easily get caught up in conversations like this. In fact, I’m certain more than one Mere Inkling reader has contemplated compiling their own creative dictionary! It’s not an insurmountable project, since it’s accomplished one word at a time.

_____

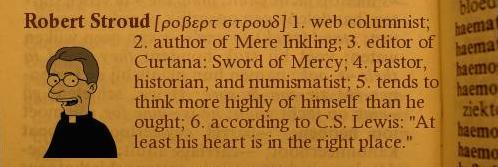

For those desiring to create their own dictionary “entries” such as the one that graces the top of this blog, there a free meme generator you can use online. Available here, it’s a fun little tool. It’s also suitable for creating a little self-deprecating humor.