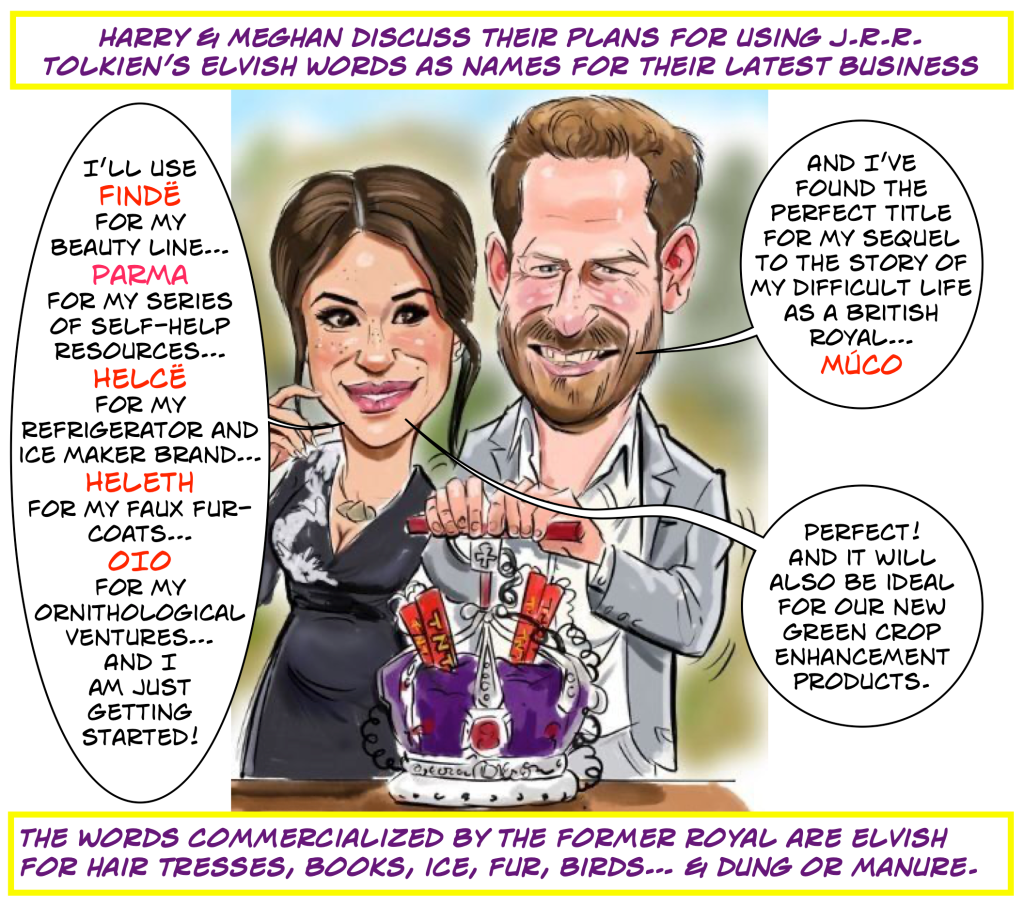

When a great author, say of the magnitude of J.R.R. Tolkien, creates ingenious new words, and even entire languages, there are several common reactions. Most readers simply respond with silent awe. Others are inspired to emulate their efforts. A small number reuse those very words as a sincere homage.

And a handful of “admirers” go so far as to “appropriate” the words themselves, for their personal benefit.

C.S. Lewis, no mean linguist himself, recognized his friend Tolkien’s brilliance. In his preface to That Hideous Strength he praised Tolkien’s yet-to-be-published Silmarillion. In a 1951 letter he mentions misspelling the word Numenor.

My Numinor was a mispelling: it ought to be Numenor. The private mythology to which it belongs grew out of the private language which Tolkien had invented: a real language with roots and sound-laws such as only a great philologist could invent.

He says he found that it was impossible to invent a language without at the same time inventing a mythology.

J.R.R. Tolkien was an internationally renowned philologist, and his impressive skill is one of the great wonders we encounter in Middle Earth. A number of words from his created languages – particularly his ethereal Elvish tongues – have been lifted to be used in commercial activities unconnected to Tolkien’s interests.

For example, Palantir. This was the word for the “seeing stone,” which played a prominent role in The Two Towers. In light of Tolkien’s love of nature, and corresponding suspicion of technological advancement, it is especially odd that the company adopting this label is on the leading edge of Artificial Intelligence.

Perhaps Tolkien’s dread would have been dispelled by one of Palantir’s disarming mottos: “We believe in augmenting human intelligence, not replacing it.”

A combat veteran of WWI, like his fellow Inkling C.S. Lewis, Tolkien was appalled by war’s horrors. Even in the War of the Rings, with its moments of glorious heroism and sacrifice, the bloody heart of Mars remains nearly invincible. Because of this mixed attitude toward war, some have wondered how he would have felt about a defense (i.e. military) corporation adopting one of his creations.

Andúril was the name of the most important weapon forged in Middle Earth. It was actually reforged from the broken fragments of Narsil, the longsword which defeated Sauron by severing the One Ring from his hand.

While this description from the Anduril company resonates with our modern ear, I am not convinced that it sounds very Tolkienesque. Anduril: “Transforming defense capabilities with advanced technology. The battlefield has changed. How we deter & defend needs to change too.”

For an article about a billionaire investor who is consumed by mining Tolkien’s tomes for the businesses he founds (PayPal excepted), check out “The hidden logic of Peter Thiel’s ‘Lord of the Rings’-inspired company names.”

C.S. Lewis’ Unconscious Sharing

In a 1965 letter, written after Lewis’ death, Tolkien commented on how his friend had used subtle variations of several Elvish words in several of his fictional works.

Tolkien says Lewis “had the peculiarity that he liked to be read to. All that he knew of my ‘matter’ was what his capacious but not infallible memory retained from my reading to him as sole audience.” Thus, he surmises that:

C.S. Lewis was one of the only three persons who have so far read all or a considerable part of my ‘mythology’ of the First and Second Ages, which had already been in the main lines constructed before we met. . . . His spelling numinor is a hearing error, aided, no doubt, by his association of the name with Latin nūmen, nūmina, and the adjective ‘numinous.’

Lewis was, I think, impressed by ‘the Silmarillion and all that,’ and certainly retained some vague memories of it and of its names in mind. For instance, since he had heard it, before he composed or thought of Out of the Silent Planet, I imagine that Eldil is an echo of the Eldar; in Perelandra ‘Tor and Tinidril’ are certainly an echo, since Tuor and Idril, parents of Eärendil, are major characters in ‘The Fall of Gondolin,’ the earliest written of the legends of the First Age. But his own mythology (incipient and never fully realized) was quite different.

An Entertaining Diversion

Years ago I linked to an entertaining game that plays on the linguistic eloquence and mystery Tolkien exhibited in naming his characters. I was delighted to see now that it is still available online.

Antidepressants or Tolkien challenges players – you can play solo, but it’s more fun with others – to guess if a given word is an antidepressant drug or the name of one of Tolkien’s characters. Don’t expect to score 100%, but do expect to smile at some of the examples.