Who among us has lived a life free of typographical errors? When we learned to type (or “keyboard”), our typing speed was influenced by the number of incorrect characters we included.

Even worse, some infernal source birthed the idea of “autocorrect,” which is occasionally useful for documents, but just as frequently deadly for emails and texts.

Lewis’ own books have included a number of typographical errors. Arend Smilde, a Dutch scholar and translator, has noted a fair number of them on his valuable website.

The truth is, it is possible for errors to creep in whenever original manuscripts are copied.

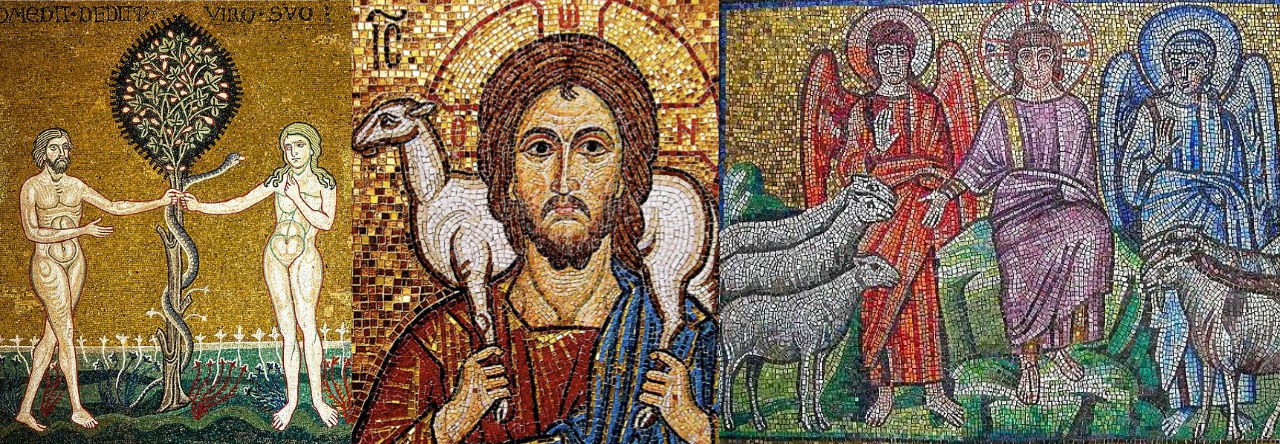

Even with the Scriptures, existing manuscripts include various minor variations, since the autographs have been lost to history.

This fact necessitates the need for “textual criticism,” and many earnest biblical scholars have devoted their lives to discerning the original text. (“Criticism” in this use, does not connote negativity. It simply refers to study, such as with “literary criticism.”)

Textual criticism diverges significantly from the so-called “higher criticisms” which frequently result in confusion and doubt.* Comparing actual texts is fundamental to the study of all literary creations.

C.S. Lewis wrote a brilliant essay entitled “Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism,” which is currently known as “Fern-Seed and Elephants.” In it, he distinguishes between the various types of criticism and affirms textual examination as utterly valid.

We think that different elements in this sort of theology have different degrees of strength. The nearer it sticks to mere textual criticism . . . the more we are disposed to believe in it. And of course, we agree that passages almost verbally identical cannot be independent. It is as we glide away from this into reconstructions of a subtler and more ambitious kind that our faith in the method waivers; and our faith in Christianity is proportionally corroborated.

The sort of statement that arouses our deepest scepticism is the statement that something in a Gospel cannot be historical because it shows a theology or an ecclesiology too developed for so early a date. For this implies that we know, first of all, that there was any development in the matter, and secondly, how quickly it proceeded.

When books are published, errors slink in. This generates errata, which are presumably corrected in any subsequent editions of the work. (It dawns on me that I’ve never seen an erratum, noting there is only one mistake in the work.)

The Genesis of Today’s Thoughts

Curiously, the article that led me to think about textual errors involves the substitution of an i for an e. The result is that for centuries, people mistakenly believed that Rome had a “Little Temple of Ridicule.” The notion was that the ancient Romans so loved humor, that they “went so far as to erect a ridiculi aedicula, or chapel of laughter.” This curious article is well worth reading (hint: it has something to do with Hannibal’s retreat).

It’s not that the idea of humor shouldn’t be celebrated. On the contrary, laughter features broadly in C.S. Lewis’ works. In a letter written shortly after his marriage to Joy, he alludes to Dante’s portrait of heaven. It is an image Lewis affirmed, and one that I happily anticipate.

Of course Heaven is leisure (“there remaineth a rest for the people of God”): but I picture it pretty vigorous too as our best leisure really is. Man was created “to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.”

Whether that is best pictured as being in love, or like being one of an orchestra who are playing a great work with perfect success, or like surf bathing, or like endlessly exploring a wonderful country or endlessly reading a glorious story—who knows? Dante says Heaven “grew drunken with its universal laughter.”

* For an informative discussion of the different forms of criticism, see this conversation. In response to the question “How is it, then, that the Higher Criticism has become identified in the popular mind with attacks upon the Bible and the supernatural character of the Holy Scriptures?” the author writes:

Some of the most powerful exponents of the modern Higher Critical theories have been Germans, and it is notorious to what length the German fancy can go in the direction of the subjective and of the conjectural. For hypothesis-weaving and speculation, the German theological professor is unsurpassed.

Some of the men who have been most distinguished as the leaders of the Higher Critical movement in Germany and Holland have been men who have no faith in the God of the Bible, and no faith in either the necessity or the possibility of a personal supernatural revelation.