“An army marches on its stomach.”* Military leaders have long recognized that it is difficult to arouse soldiers weakened by deprivation. Sadly, though, even a king of Israel could be foolish enough to ignore that and order his soldiers to fast before a battle.

While logisticians rarely receive the accolades of their peers who serve directly in combat, they have always been vital members of successful military ventures.

While they are concerned with securing and transporting all requirements, such as ammunition and medical supplies, there is a single necessary requirement for all campaigns. Without sustenance, soldiers will desert the flag and even the most steadfast will fall.

Nutritional value is the first priority. Palatability has historically been a distant afterthought. This has given rise to innumerable jokes made by veterans about the “combat rations” provided to them. While these “menus” have vastly improved in recent years, they remain fodder for much humor.

And even the most delicious food choices become monotonous when they are limited to a small range. In 2002, I visited a remote military detachment supplied with adequate pallets of Meals Ready to Eat, but begging for variety. They had hundreds of meals available, but only two or three different meal options! Civilians, in contrast, can readily purchase a far wider range of entrees.

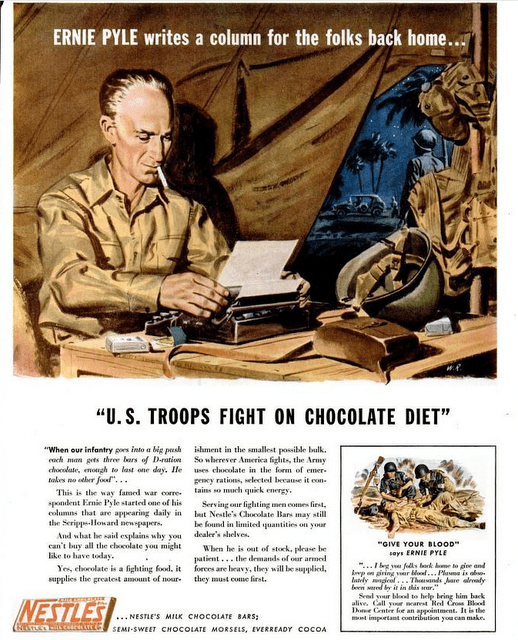

During the Second World War, the United States invested major efforts in making the combat meals more appealing. Various candies found their way into K-rations, in addition to necessities like toilet paper and cigarettes. In a comprehensive overview of the history of rations, the U.S. Army Quartermaster Foundation points to the main reason for complaint during WWII.

Like other unpopular items, misuse was a contributing factor to the waning popularity of the K ration. Although designed to be used for a period of two or three days only, the ration occasionally subsisted troops for weeks on end. . . . Continued use reduced the acceptability and diminished the value of the ration.

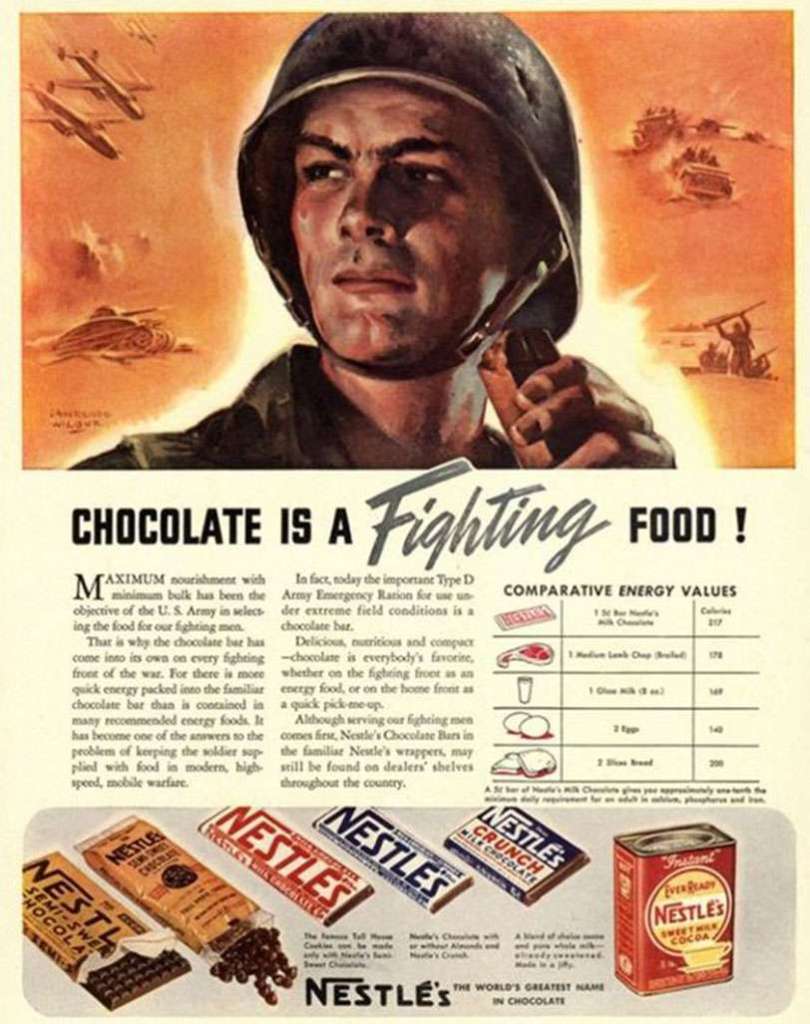

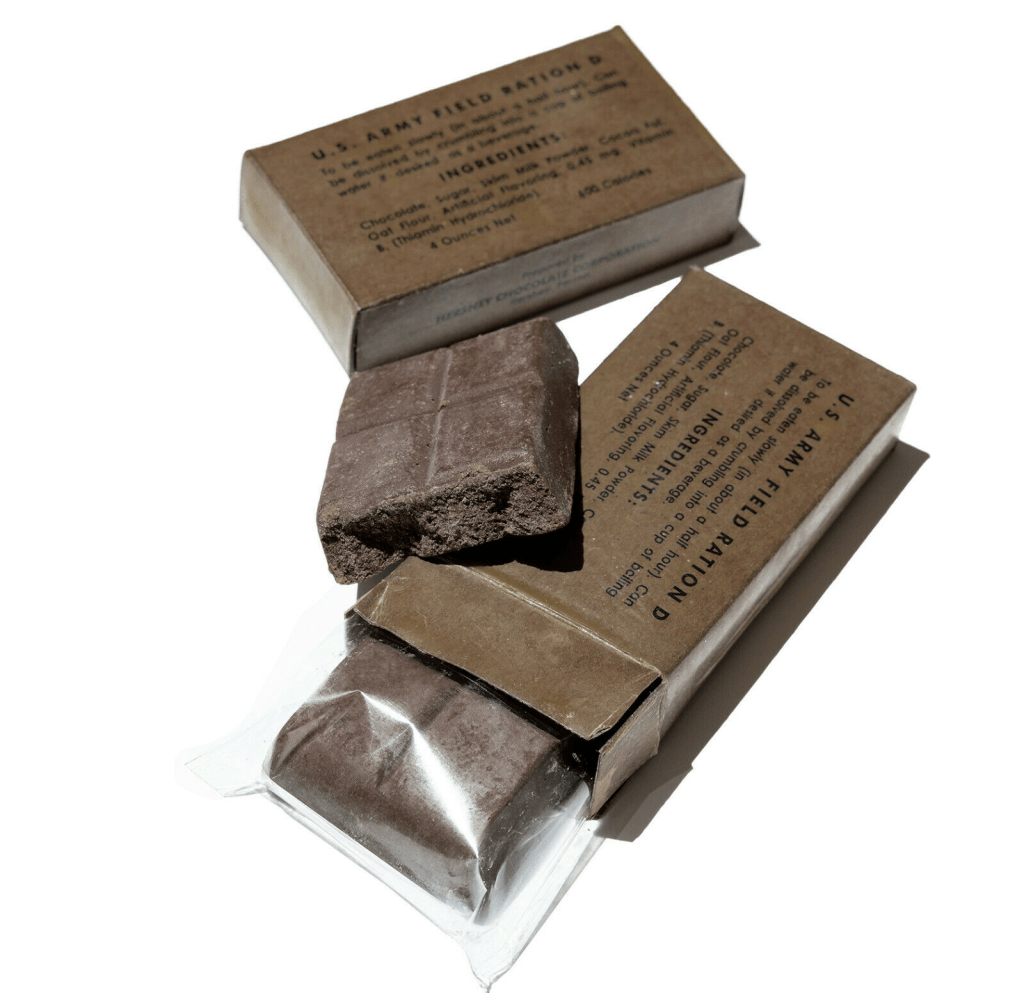

Adding confectionaries to rations made the meals more welcome. Chocolate was always a favorite, but the initial American versions left much to be desired.

My research was, in fact, prompted by a recent post on “Chocolate in WWII” in Pacific Paratrooper. (It is one of the very best military blogs on the internet.) They describe how the military approached a major American confectioner with a simple list of requirements (the last one is best appreciated by older veterans).

The Hershey Chocolate company was approached back in 1937 about creating a specially designed bar just for U.S. Army emergency rations. According to Hershey’s chief chemist, Sam Hinkle, the U.S. government had just four requests about their new chocolate bars: (1) they had to weigh 4 ounces; (2) be high in energy; (3) withstand high temperatures; (4) “taste a little better than a boiled potato.”

Sadly, many “who tried it said they would rather have eaten the boiled potato.” Well, it was the thought that counted, right?

There is a legend that during the war a German officer was confronted with American desserts and determined that the abundant resources of the United States signaled doom for the Nazi cause. The story likely has a fictional origin.

In the 1965 film Battle of the Bulge, Wehrmacht Colonel Hessler, shows his commanding general a treasure confiscated from American soldiers.

Hessler: “General, before you go, may I show you something?”

General: “What is it?”

Hessler: “A chocolate cake.”

Kohler: “Well?”

Hessler: “It was taken from a captured American private. It’s still fresh. If you will look at the wrapping, general, you will see it comes from Boston.”

Kohler: “And?”

Hessler: “General, do you realize what this means? It means that the Americans have fuel and planes to fly cake across the Atlantic Ocean. They have no conception of defeat.”

C.S. Lewis & Rations

Military rations during the First World War were more primitive than those provided twenty years later. One difference for the British is that they were granted a half gill of rum (or a pint of porter) each day.

This alcohol distribution was at the discretion of the commanding general, which meant that it was not available in the trenches. This was in the spirit of the American “General Order Number 1,” which typically applies to alcohol, and sometimes prohibits its presence throughout an entire theater. (I can personally attest to the ability of some elements, such as Special Ops, to circumvent such restrictions.)

C.S. Lewis wrote with some frequency about the rationing endured by the British public, during and after the world wars.⁑

Unfortunately, I’ve only uncovered one Lewisian reference to his own experience with military cuisine. In a 1917 letter to his father, he reveals that meals were not always appealing, even during training, prior to deploying to the war zone.

First of all came the week at Warwick, which was a nightmare. I was billeted with five others in the house of an undertaker and memorial sculptor. We had three beds between six of us, there was of course no bath, and the feeding was execrable.

The little back yard full of tomb stones, which we christened ‘the quadrangle,’ was infinitely preferable to the tiny dining room with its horse hair sofa and family photos.

When all six of us sat down to meals there together, there was scarcely room to eat, let alone swing the traditional cat round. Altogether it was a memorable experience.

A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War describes how WWI affected C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. After relating a passage following Miraz’s defeat of Caspian’s force, when the momentarily defeated were “a gloomy company that huddled under the dripping trees to eat their scanty supper,” the author observes:

The military blunders, the fruitless acts of bravery, the bone-chilling rain, the meager rations: there were many days and nights just like these along the Western Front. Imaginary beasts aside, such scenes could have been lifted from the journal of any front-line soldier.

Like Tolkien, though, Lewis includes these images not for their own sake, but to provide the matrix for the moral and spiritual development of his characters . . .

Rations in Ukraine

Although the eyes of the world are riveted today on the war in Ukraine, there are currently 110 armed conflicts being monitored by the Geneva Academy. However, since Ukraine is in the news daily, it is worth noting both modern armies are employing military rations.

Apparently, Ukrainian troops have great Meals Ready to Eat (MREs). “Most importantly, when making, eating, or even talking about the food, the men seem to be genuinely happy.” The MRE link in this paragraph contains the details, including the note that “among the contents, you’ll find a small packet of dried apricots and a dark chocolate bar.”

There is also a vendor on ebay who sells what are purported to be captured Russian supplies, including a confiscated chocolate bar. The candy appears to be conventionally purchased, but could be part of an illicit chocolate conspiracy finding its way to the Russians from Latvia. “The Russian confectionery company ‘Pobeda’ ПОБЕДА has been producing chocolates, truffles, waffles and other types of sweets for more than six years in Ventspils, via a Latvian subsidiary.”

A month ago in Russia, “Pobeda” received thanks from an organization called the “Battle Brotherhood” for the fact that since the beginning of the Ukrainian war, the company has sent at least 15 tonnes of its products to Russian soldiers.

Chocolate does indeed appear to fuel armies. For a fascinating article on how chocolate can also be used to promote propaganda, check out this Ukrainian site.

Russian propaganda continues to dehumanize Ukrainians with the help of outright fakes.

Another “proof” of our apparent bloodthirstiness was the image of a chocolate bar with a remarkable name “Death of Alyoshka.” A portrait of a boy in a helmet with a mourning ribbon is placed on the wrapper of the confectionery. Propagandists claim that Ukrainians wish Russian children dead.

Become an MRE Connoisseur

If you are curious about the contents of various international MREs that are available for purchase by civilians, visit MREmountain, which began “in 2017 when people discovered the hobby of trying army rations.”

Most veterans, I suspect, would find the “hobby” of eating military rations rather peculiar. But then again, you can check out the French options, which the site labels “The best MRE in the world.” Only there, I imagine, could one discover “meals not found in any other MRE like Kebob Meatballs, Duck Confit, Deer Pate, Wild Boar.”

And, of course, France’s 24-hour ration also includes chocolat müesli, chocolate biscuits, five snack bars (at least one of which is pure chocolate), and a hot cacao packet. Yummy. It appears that les Français also consider chocolate to be a staple of modern soldiers.

* This quotation has been attributed to Napoleon and Frederick the Great. Whatever its modern origin, it is obvious starvation and its frequent companion, disease, have crippled as many armies as blade and shot.

⁑ “Mock Goose and Other Dishes of the War-Rations Diet” offers some interesting thoughts on this subject.