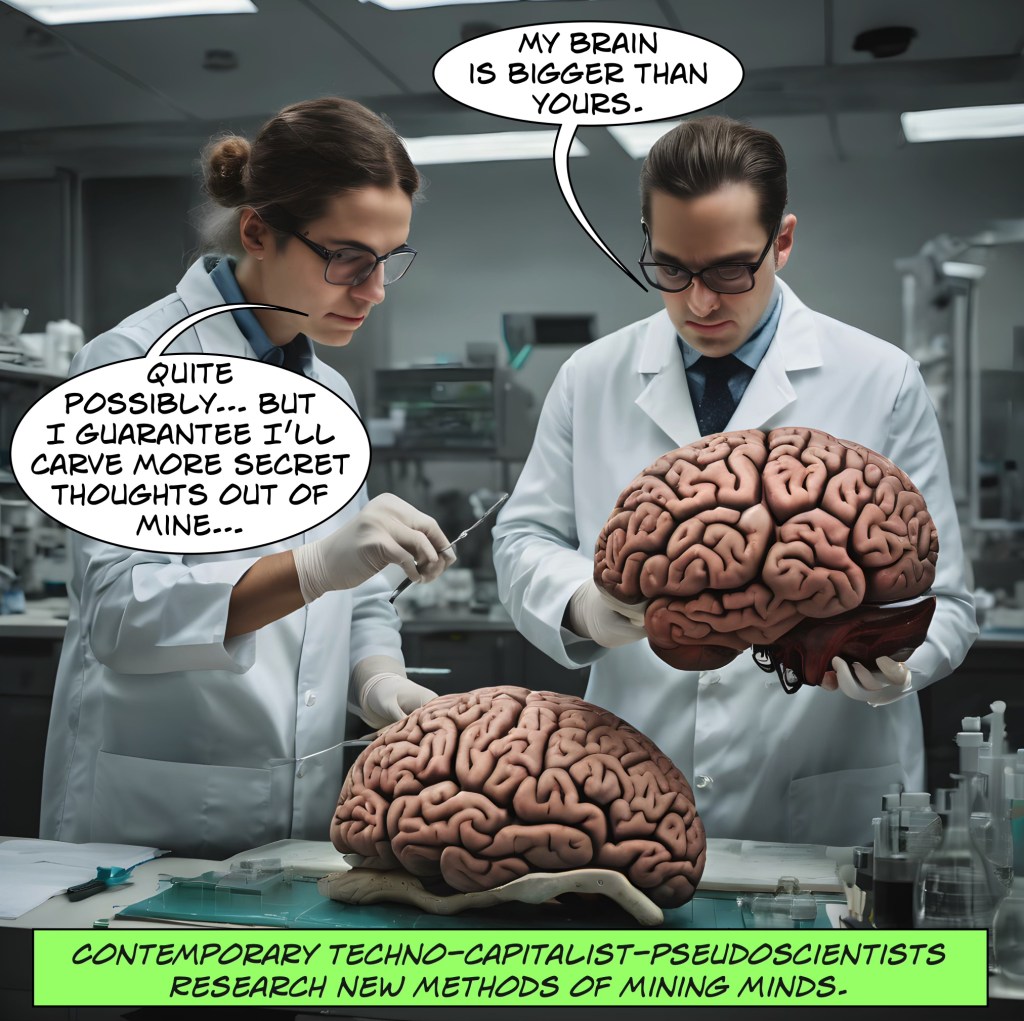

When we are young, it is common for us to think of “brain” and “mind” as synonyms. Today, (potentially nefarious) scientific advances are probing the brain, to gain commercially beneficial access to the mind.

What would C.S. Lewis think? Perhaps his 1955 comment about commercialism provides a hint?

I wish we didn’t live in a world where buying and selling things (especially selling) seems to have become almost more important than either producing or using them.

Seventy years later it is strange to apply this economic principle to the ineffable nature of the mind. And it’s even more odd to apply Lewis’ observation to this situation. He would definitely consider using one’s brain more important than marketing it.

As a young man, C.S. Lewis used the word “brain” when referring to dredging up pleasant memories of past holidays. Even in 1921 he realized that memories are capable of adding a resplendent glow to past experiences.

I still feel that the real value of such a holiday is still to come, in the images and ideas which we have put down to mature in the cellarage of our brains, thence to come up with a continually improving bouquet.

Already the hills are getting higher, the grass greener, and the sea bluer than they really were; and thanks to the deceptive working of happy memory our poorest stopping places will become haunts of impossible pleasure and Epicurean repast.

It is certainly no accident one neurologist calls the relationship between brain and mind “the enchanted loom.”

So, why is it that we began with a question about the commercial incentive to secure the “brain data” of willing – and unsuspecting – people?

Well, it turns out that since “tech companies [already] collect brain data that could be used to infer our thoughts,” it is “vital we get legal protections right” (MIT Technology Review).

Two months ago, California amended their Consumer Privacy statute to include neural data. It quite appropriately immediately follows the protection of “a consumer’s genetic data.) According to the MIT report:

The law prevents companies from selling or sharing a person’s data and requires them to make efforts to deidentify the data. It also gives consumers the right to know what information is collected and the right to delete it.

Which is crucial because:

Brain data is precious. It’s not the same as thought, but it can be used to work out how we’re thinking and feeling, and reveal our innermost preferences and desires (emphasis in original).

Brain Versus Mind

Before proceeding, let’s clarify the difference between the brain and the mind. The brain is a physical organ which controls our autonomous (typically unconscious) bodily functions such as our heart rate and digestion. It also controls our movements and, to a degree, our emotions.

The mind, on the other hand, is not physical. It cannot be seen or touched, due to its intangible nature. It can, however, be examined and manipulated, which is another subject I have addressed elsewhere.

The mind is involved with thinking and deciding actions. When they are physical actions, such as whether to indulge in a second helping of dessert, the physical actions involved in that indulgence are relayed by the brain to the appropriate muscles required to perform the act.

The mind is commonly equated with our consciousness. As such, it exists in that realm where we can make moral evaluations and arrive at good decisions, even when they may be against our own self-interest.

Here is a simple illustration of the difference. The brain enables a body (person) to rise and possess the balance to walk along a winding path. The mind allows the person to determine which path is the noble or life-affirming option among the innumerable paths before us.

The brain can only assess a path in the physical sense, through vision, balance, etc. The mind comprehends that “path” means far more than physical orientation.

In C.S. Lewis’ address “Transposition,” he discusses his concept of how simpler concepts and knowledge are sometimes forced to attempt to convey greater knowledge. This can only be accomplished imperfectly. Britain’s monthly The Critic offers an excellent discussion of how transposition illuminates Lewis’ “philosophy of the mind.”

A transposition occurs, he argues, when a richer set of conceptual categories must necessarily be represented by a poorer set of conceptual categories.

In his essay “Is Theology Poetry?” Lewis describes how the mind transcends the physical limitations of the brain itself.

If minds are wholly dependent on brains, and brains on bio-chemistry, and bio-chemistry (in the long run) on the meaningless flux of the atoms, I cannot understand how the thought of those minds should have any more significance than the sound of the wind in the trees.

I might summarize this by declaring “we are more than our brains.” Atheists, sadly, will disagree. They acknowledge our accomplishments may leave behind some ephemeral residue, but once that brain perishes due to the lack of oxygen, everything that is/was us, evaporates, never to exist again.

As the leader of the Church in Jerusalem wrote, without Christ and the promise of the resurrection, what hope exists?

What is your life? For you are a mist that appears for a little time and then vanishes. (James 4).

And this returns us to the question of precisely what these mind scientists are after. Knowing more about the brain is valuable, so that we might prevent and treat the diseases which assail it.

But far more valuable, I suspect, is a window into the mind. So we might discover keys to how we exercise the miracle of thought.

Knowing fallen humanity’s propensity to abuse science and technology, forgive me if I remain a bit leery of experiments such as this. And, for those who may be tempted to get involved with developing technologies and allow their brains/minds to be probed for a pittance, I encourage you to ponder the ramifications a little longer.

C.S. Lewis Bonus Material

The quotation above from “Is Theology Poetry?” may have whetted your curiosity about the broader context of the sentence. For those who are interested, read on. [Personal note: I absolutely love his phrase “mythical cosmology derived from science…”]

When I accept Theology I may find difficulties, at this point or that, in harmonising it with some particular truths which are imbedded in the mythical cosmology derived from science. But I can get in, or allow for, science as a whole.

Granted that Reason is prior to matter and that the light of that primal Reason illuminates finite minds. I can understand how men should come, by observation and inference, to know a lot about the universe they live in.

If, on the other hand, I swallow the scientific cosmology as a whole, then not only can I not fit in Christianity, but I cannot even fit in science.

If minds are wholly dependent on brains, and brains on bio-chemistry, and bio-chemistry (in the long run) on the meaningless flux of the atoms, I cannot understand how the thought of those minds should have any more significance than the sound of the wind in the trees.

And this is to me the final test. This is how I distinguish dreaming and waking. When I am awake I can, in some degree, account for and study my dream. The dragon that pursued me last night can be fitted into my waking world.

I know that there are such things as dreams: I know that I had eaten an indigestible dinner: I know that a man of my reading might be expected to dream of dragons.

But while in the nightmare I could not have fitted in my waking experience. The waking world is judged more real because it can thus contain the dreaming world: the dreaming world is judged less real because it cannot contain the waking one.

For the same reason I am certain that in passing from the scientific point of view to the theological, I have passed from dream to waking. Christian theology can fit in science, art, morality, and the sub-Christian religious. The scientific point of view cannot fit in any of these things, not even science itself (“Is Theology Poetry?”).

Those who wish to read more about C.S. Lewis’ thoughts on Transposition and the mind are invited to read the following excerpt, in its fuller context.

. . . Transposition occurs whenever the higher reproduces itself in the lower. Thus, to digress for a moment, it seems to me very likely that the real relation between mind and body is one of Transposition.

We are certain that, in this life at any rate, thought is intimately connected with the brain. The theory that thought therefore is merely a movement in the brain is, in my opinion, nonsense; for if so, that theory itself would be merely a movement, an event among atoms, which may have speed and direction but of which it would be meaningless to use the words “true” or “false.”

. . . We now see that if the spiritual is richer than the natural (as no one who believes in its existence would deny) then this is exactly what we should expect. And the sceptic’s conclusion that the so-called spiritual is really derived from the natural, that it is a mirage or projection or imaginary extension of the natural, is also exactly what we should expect; for, as we have seen, this is the mistake which an observer who knew only the lower medium would be bound to make in every case of Transposition.

The brutal man never can by analysis find anything but lust in love; the Flatlander never can find anything but flat shapes in a picture; physiology never can find anything in thought except twitchings of the grey matter.

It is no good browbeating the critic who approaches a Transposition from below. On the evidence available to him his conclusion is the only one possible. . . .

I have tried to stress throughout the inevitableness of the error made about every transposition by one who approaches it from the lower medium only. The strength of such a critic lies in the words “merely” or “nothing but.” He sees all the facts but not the meaning.

Quite truly, therefore, he claims to have seen all the facts. There is nothing else there; except the meaning. He is therefore, as regards the matter in hand, in the position of an animal.

You will have noticed that most dogs cannot understand pointing. You point to a bit of food on the floor: the dog, instead of looking at the floor, sniffs at your finger. A finger is a finger to him, and that is all. His world is all fact and no meaning. And in a period when factual realism is dominant we shall find people deliberately inducing upon themselves this doglike mind (“Transposition”).